Most of the value of education comes from being able to signal high levels of human capital, rather than human capital being caused by schooling. The extent to which this is true differs by context, but the overall picture is corroborated by the data: the last year of degree completion pays 3 times as much as the average year (10%), the effects of schooling are observed between individuals but not between nations, and most of what is learned in school is gradually forgotten.

Academics and scientists are part of the education system; they are relied on to produce instructors and teach university students. But they also serve two separate functions: to produce scientific research and be our day’s priestly caste.

If the purpose of an institution becomes to be less valuable over time, it will consequently decline in prominence. For this reason, and for several others, I predict that academia as an institution will become far less relevant around the turn of the century.

Priestly caste, but for who?

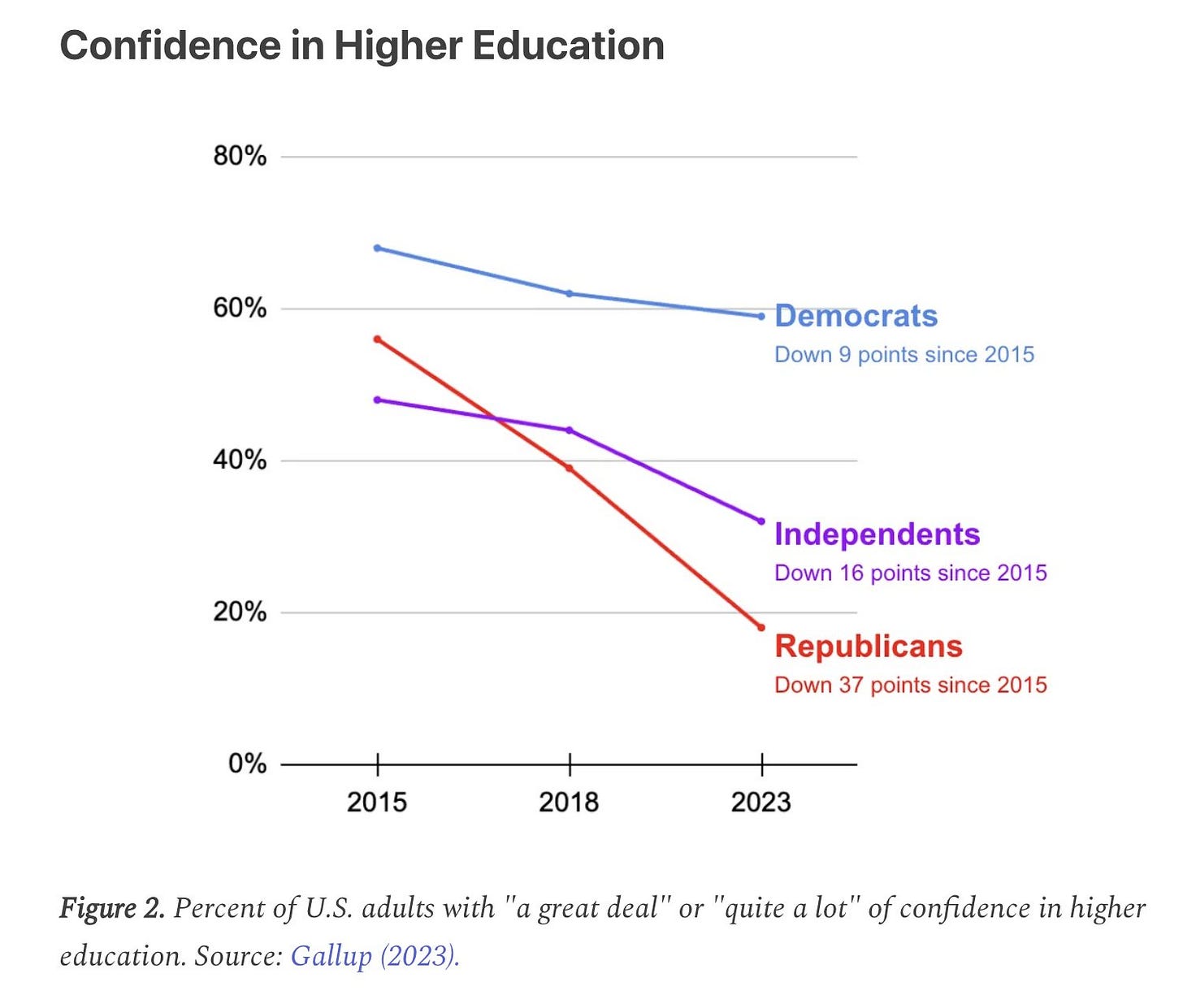

“Trust the science” is becoming an old meme, but it does accurately describe the admiration that Democrats hold for higher education institutions. If only one side of the ideological isle trusts the institutions, then they will not be able to serve as a priestly caste as well as they used to back in the day.

Innovation, but where?

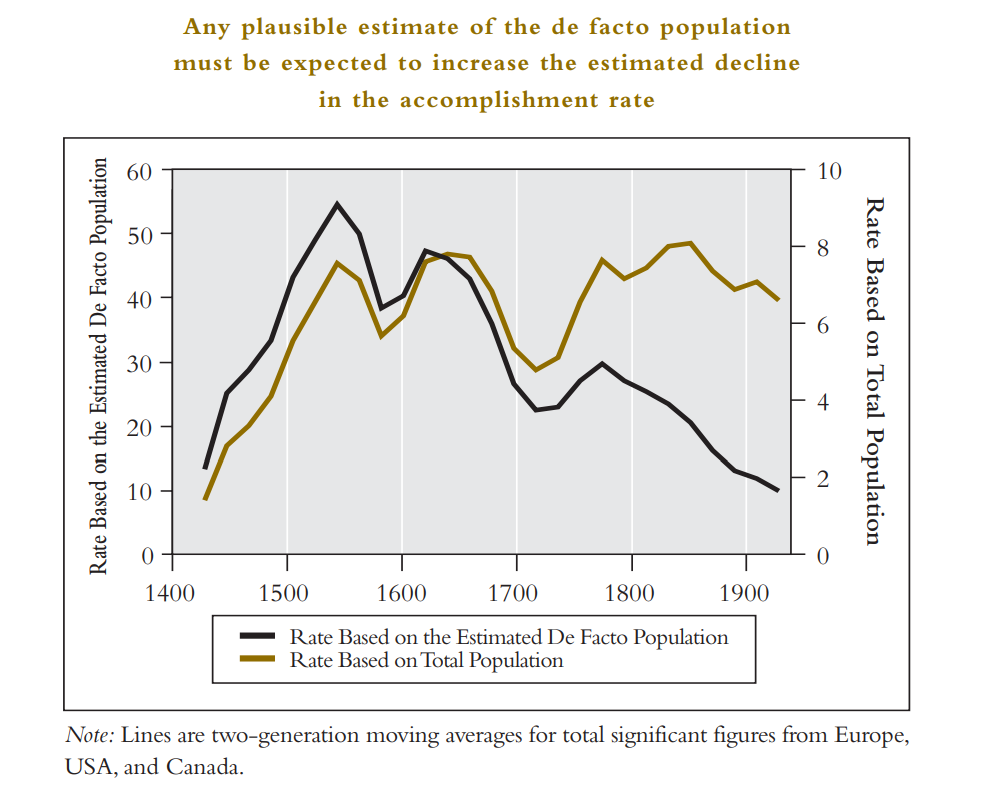

There are several proxies that one can make for the rate at which innovation happens in the world. Each has their own separate problems and biases, but fortunately, they agree that innovation peaked somewhere around the late 19th Century.

With one exception: the raw number of significant figures by year. This increase is biased by two things: first, that more people are able to realize their potential with increased levels of literacy and less subsistence poverty and second by the increase in the overall population. When those two factors are adjusted for, the decrease in the rate at which people become significant figures has been occurring since the 1500s.

The existence of this decline is not exactly controversial; Peter Thiel has been arguing that innovation has stagnated everywhere but computing since the early 2010s, and few have attempted to challenge this statement seriously. Cowen makes the case for it well in his 2019 paper on the matter, noting that the GDP per capita and productivity growth are slowing down, and that most indexes of significant figures and events find temporal decreases.

If we live in a world where innovation is not happening as often as it used to, then universities will become less prestigious. It does not matter if they are responsible for this decrease, only that their purpose of encouraging innovation and discovery is now less relevant than it used to be.

AI

I oscillate somewhere between the positions of AGI denialism and agnosticism, though whether “AGI” ever comes is not as relevant as the fact that LLMs serve as a supplement and replacement for human labour. Because of that, they can now do homework.

Universities have to label students in some way, whether that’s homework, classroom tests, take home tests, attendance, essays, or projects. AI can do all of these things except for attend class (which is rarely mandatory anymore) and take tests. Practically anybody with an IQ of over 100 can use an LLM to pass all of their classes, independent of their personality. If universities still want to function as credentialing institutions, they will have to adapt and rely more on offline testing to filter students out.

Will they do this? Presumably, to an extent, but I doubt they will increase the prevalence of offline testing enough. The method by which students are graded is up to the professor, and professors don’t have much of an incentive to make those systems effective.

Beyond the signalling critique, domain expertise in computing and STEM is now less valuable with the advent of AI. I don’t think that a firm today can ignore credentials and select employees for just IQ, but that might be possible now with the advent of AI. Domain expertise in physics, computing, chemistry, and genetics has never been easier to search for with LLMs, making whatever knowledge that universities supplied their students with less relevant.

Admittedly, in the old days, people predicted that the internet would make higher education obsolete because anybody could look up anything. Which did not happen. But AI doesn’t just know things, it can do things: most importantly coding and writing, the core skillset of 95% of white collar jobs.

This will not make university degrees and selection obsolete. Prompting and interacting with an LLM is still a skill: it requires people to read and write, which probably correlate even more highly with intelligence than the execution of specific technical tasks. But it does make them less relevant, as LLM reduces the floor at which people can produce now.

Demographics

With all of the doom about population projections in the West, what’s funny is that the UN actually seems to be underestimating the extent to which population collapse will occur in the first world. The global decline in TFR has been happening since the 50s, and shows no signs of stopping. They also have overly optimistic forecasts of life expectancy over time, which also inflate population projections.

To some extent I cannot fault them for thinking this; my own prediction is that fertility will stop declining around 2030, as the drop is largely driven by tech and recent cultural changes. In addition to this, I predict that culture in societies with consistently low fertility will shift slowly towards high fertility norms, though I admit this is a prediction I’m not exactly confident in.

Nonetheless, a shrinking native population means less students, faculty, and capital will be flowing into universities. For HBD reasons, immigrants outside of East Asia (which is going to be tanking in terms of population too) will not be a sufficient replacement for the native populations of developed countries. In fact, if universities don’t properly filter their students, a surplus of immigrants will cause the universities to decline in quality. Which is inevitable, really, due to the way Democratic politics work and the fact that any selection mechanism will be imperfect.

Prestige lags quality

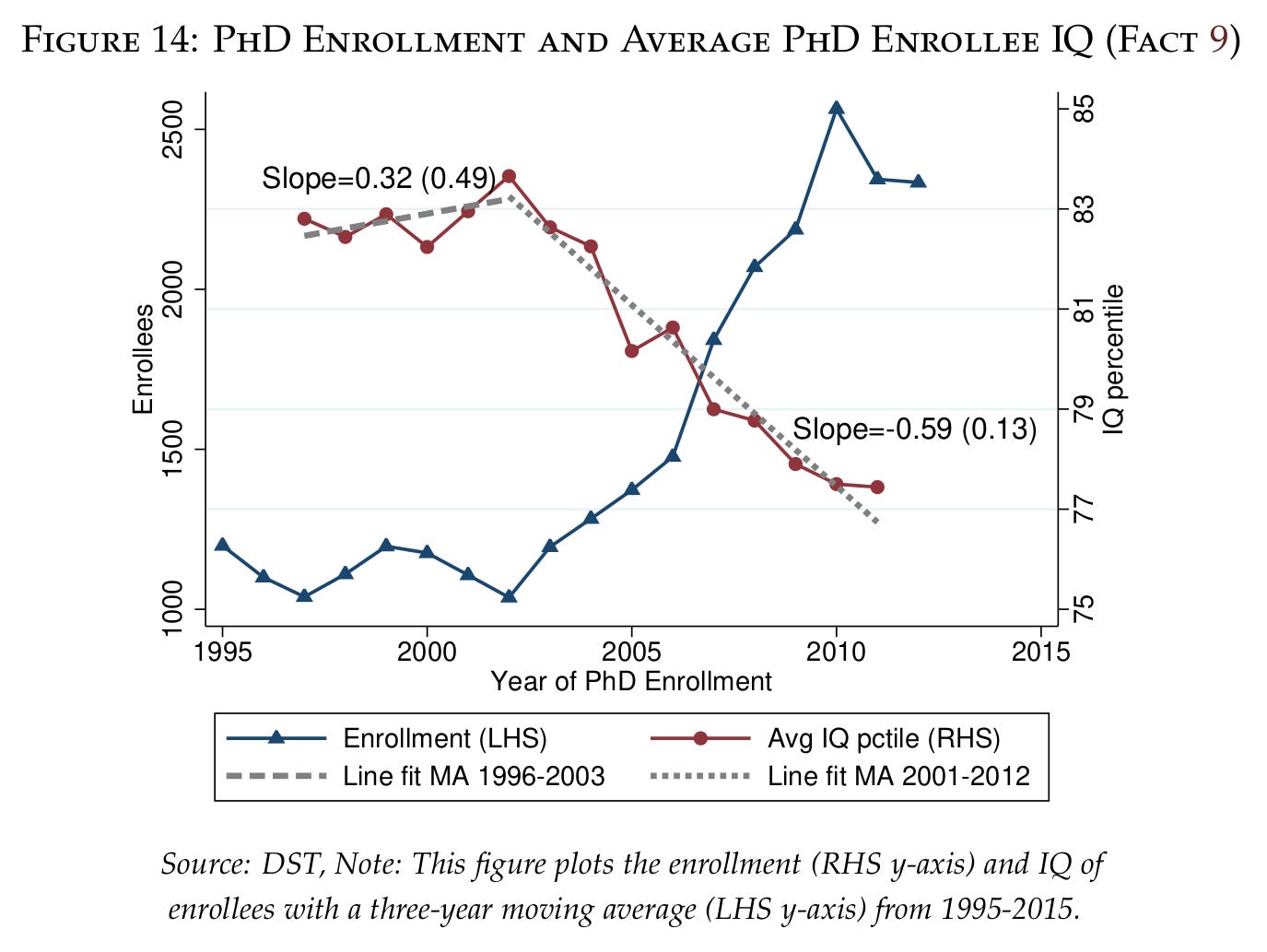

Over time, educational institutions have been graduating more and more people from their programs. Most of this is not due to improvements made to the education system, but to decreases in the standards for graduating, meaning that the degrees have become devalued over time. Notably, the date at which PhD enrollment skyrocketed due to a policy change in Denmark is also the date at which the average IQ of a PhD student decreased from about 115 to 110.

As of now, universities are coasting on the prestige that they accumulated from the somewhat competent PhD students of the late 20th Century. If we have reason to believe that the degree-holders of today are less competent than the ones of 40 years ago, then the prestige of the institutions that they create should also be expected to decrease.

So?

I’m not interested in starting a “graduate school blackpill blog”, where I spit out a bunch of statistics about PhD students failing to find jobs and screaming at people not to attend. That’s the way losers think. Life is too particular and context-dependent for advice to work. Some have even called for people to attend state schools instead of prestigious Ivy-tier ones, which is a terrible idea. Prestige is falling much more in lower-ranked universities than higher ranked ones, which can still afford to select for a student body with an average IQ of about 125 or so.

What I will bet on, however, is that if academics want to be taken more seriously, they will want to have a popular following, like Haidt, Hanania, or Henrich. Or, at the very least, be respected by people with a popular following (e.g. how Dwarkesh Patel platforms a lot of niche academics). Traditionally, having a clout in the popular sphere is not given the same status as clout in academia — scientists have even created a statistic called the “Kardashian index” which measures the discrepancy between a scientist’s social media following and publication record, with the implication that academics with a large social media following and poor publication numbers are just celebrities. Even now, I think the opposite is true: paper pushers with no presence are less valuable than “celebrities” who actually write things that people want to see.

Even if, consciously, there is a pseudo-elitist disposition that causes people to be skeptical of academics with a large popular following, on the unconscious level, people will respect academics who are able to command attention.

My full reaction to sebjenseb's new article on academia and prestige:

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION HOAX:

Huebner's finding that innovation peaked between 1840 and 1880 is wild. Every modern convenience -- phones, computers, refrigeration, air conditioning, cars -- didn't become accessible to consumers until the 1950s. These conclusions are radically contradictory to "common sense,” but I’m open to them.

Murray's estimate that "rate of accomplishment" peaked in 1550 is even more astounding. It debunks the entire concept of the "industrial revolution." According to Murray, we are less innovative than Europeans in the 1400s. If peak invention occurred in 1550, and everything since then has been downhill, this challenges a few assumptions:

1. That the dysgenic selection of the 18th century is responsible for a decline in innovation (the decline began two centuries earlier);

2. That democracy or liberalism is at fault (again, two centuries late)

3. That warfare is bad for innovation (there’s no correlation, maybe even a positive correlation between military deaths per capita and innovation)

THE EVERYTHING CRISIS:

It’s not just academia that is becoming less prestigious. Everything is becoming less prestigious: corporations are less productive, businesses are less efficient, anyone can call themselves a CEO, anyone can be a college graduate, it's all worthless. It's an "everything crisis" of prestige. As a result, people are ghettoizing into political theologies where prestige is revived within cloistered spaces. E-celebs are prestigious within their internet circles. This is more volatile and less stable than the traditional university system, but so was the "prestige" of a 15th century inventor.

WHAT IS PRESTIGE?

Prestige is "social recognition and acclaim." In the 16th century, inventors didn't get much recognition and acclaim. Who even knows the name of the guy who invented the pocket watch? Anyone? (Henlein, 1510) But we know Edison and Tesla because the prestige of invention started to exponentially increase as it started to affect the lives of common people. Isaac Newton was one of the first “celebrity scientists,” and the Royal Society helped increase his prestige. Everyone knows who Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Elon Musk are. They are famous, but they are not necessarily prestigious. It seems that innovation prestige peaked around the time of Tesla's death in the 1940s, and since then, Americans have become increasingly cynical about inventors.

Part of this might have to do with sci-fi. On the one hand, sci-fi oversells science, so that real life seems disappointing. On the other hand, it fear-mongers (Frankenstein) about the negative effects of technology. Most Americans see social media and automation as the fruit of technology, and they hate it (even as they use it and benefit from it).

THE GRADING APOCALYPSE:

The problem of incentives in grading is huge. Universities are never punished for grade inflation. Grade inflation is just as problematic as real inflation, but from the reverse. Whereas monetary inflation destroys the wages of the poor and the savings of the middle class, grade inflation destroys our trust in institutions, because it levels the playing field and destroys competence. There is absolutely no will in academia to fight this -- not even from conservatives. Conservatives are too busy fighting "wokeness" and "gender studies." No one is willing to start firing professors or holding them accountable for handing out A's like breadsticks at the Olive Garden.

AI INTERVIEWS:

Companies have always had difficulty testing employees for competence. That's why degrees are valuable -- they tell companies something about employees, and help filter out low-value candidates. But if a degree becomes worthless, then they need another way to filter employees. However, interviews take time and are expensive. Anyone who goes through a corporate hiring process understands that it's not just one manager taking one hour to hire a person. It's four rounds of interviews with ten different people. Assuming a company is paying every $100 an hour ($200k salaries), that's $4,000 just to get a person through the interview process. If you have 100 applicants, that's $400,000 just to hire a single person for a single position.

Maybe this is where AI saves the day. AI spends hours and hours putting applicants through various hoops without any human oversight or interview necessary. If the applicant satisfies the AI, then they move on to a real human interview, which hopefully is a one-and-done with their direct manager, to control for personality defects and clear mental illness. Basically, the job of AI is to construct a virtual job environment for the applicant, and force them to waste enormous amounts of time succeeding in that environment. It's a bit like Ender's Game.

BIRTH-RATES:

The graph you show is amazing. Between 1972 and 2007, the birth-rate-acceleration "slammed the brakes." What I mean by this is that during those 35 years, the decline in the birth-rate slowed dramatically, to the point that in 2007 it seemed like birth-rates may have begun to turn positive again. EDIT: I originally misread this as USA data, but it's actually global data.

Seb says: "my own prediction is that fertility will stop declining around 2030, as the drop is largely driven by the increase in smartphones and internet use. In addition to this, I predict that culture in societies with consistently low fertility will shift slowly towards high fertility norms"

I am more cynical here, because I believe low fertility is being driven by biological factors, both in terms of psychology and biological fertility. As people become more mentally ill, LGBTQ+, neurotic, fearful, and risk averse, they want less kids. And then even if they want kids, they can't have them because their reproductive organs aren't functioning properly. Even the Amish are seeing a decline in fertility. This doesn't rely upon mutational load theory, because it can be a function of microplastics and forever chemicals. No cultural revolution can fight this, at least not without biologically changing our environment. And even if we did get rid of all the microplastics, the effects are epigenetic, and therefore heritable. You can't reverse these effects without inducing a massive genetic bottleneck, which takes time to bear fruit "naturally" (meaning, no eugenics).

Yes, eventually humans will evolve to cope with microplastics by overcompensating with ridiculous amounts of testosterone production and excessive sperm counts. But that type of evolution would take several generations, and I don't expect to see the selective effects becoming visible in this century. But that's an assertion that needs to be proven by mathematical models. The problem is that most of these models contain assertions that don't account for the heritability of fertility, and instead rely on ad hoc sociological models in an area where we have no historical data, because fertility rates have never been this low before.

I would trust a successful businessman over a random person with a PhD in gender studies.Even if a plumber has a slightly lower iq that a colonial oppression studies scholar,I would still favor him to better complete 99% of given tasks,considering lower neuroticism and narcissistic that the activist upper cllass is cultivated with.If universities grade people on leftists instead of skills/competence/test scores why should we assign value to their judgements