The case for IQ measuring intelligence is fairly simple. The positive manifold, that all intelligence tests positively correlate with each other, has been observed within every intelligence test battery to date. If enough subtests are in the battery, then the reliability of the composite score will be high, about .9 on average. The existence of the positive manifold has been observed in the largest test batteries, meaning that it is very unlikely that it exists due to cherry picking on part of test constructors.

While there is only one case for IQ measuring intelligence, there are multiple cases against it, so each must be addressed individually. The number of criticisms of IQ approaches infinity, fortunately most of them cluster in six different categories:

Low validity: IQ scores can only explain so much variance in life outcomes, which implies that they are not measuring intelligence.

Sampling critique: the positive manifold is an artefact of test construction.

Test-taking ability: IQ scores are biased by the fact that people differ in their ability to take tests.

Universality: IQ is a Western concept and/or test scores are biased by demographic indicators like race, class, sex, age, and culture of origin.

Test anxiety: IQ scores are biased by the fact that some people experience anxiety while they take tests, causing their scores to decrease and hiding their true levels of intelligence.

Effort: some people put more effort into tests than others, causing the scores to be conflated with personality traits and random variance.

Low Validity

In terms of life outcomes, the strongest and most relevant correlation IQ has is with job performance (r = .5), meaning IQ scores statistically explain 25% of the variance in job performance. Beyond that, IQ is related with being slightly better at everything: intelligent people tend to be more honest, less criminal, less likely to divorce, and higher in socioeconomic status. The one consistent exception to this rule is happiness: IQ and happiness do not correlate.

These low correlations could be explain by the fact that individuals vary in their goals: somebody might not be interested in being wealthy, but prefers to be fit and to have a wide social network. This theory is hard to test empirically — people might claim that they don’t want to be wealthy, but it’s impossible to tell how honest these kinds of responses are. The theory is probably true, but it is difficult to know the extent to which it is.

Traditionally, the IQ-defenders have objected to the validity critique by arguing that the pearson correlation coefficient (r) should be used over the R^2 statistic when evaluating the strength of a predictor. I personally never particularly liked this line of argument; if IQ only explains 25% of variance in job performance, then 75% of the residual variance must be caused by something else, like passion, personality, or specific cognitive/physical talents.

There are only two ways to go from here: either intelligence isn’t that important, or IQ tests are not good at measuring it. As I document later, most of the proposed biases, like test anxiety and effort, either have null or negligible effects, so the answer appears to be the former.

Sampling critique

The sampling critique argues that the existence of a univariate general intelligence factor is an artefact of testing only a small fraction of mental abilities. I don’t take this critique seriously, since most intelligence test batteries are fairly diverse: they tend test verbal, mathematical, visualspatial, memory ability, and sometimes even more abilities. As I documented previously, the positive manifold also exists in test batteries that have an extremely large number of tests, making it unlikely that the manifold exists due to selective sampling.

Because of this, people have pivoted to identifying specific cognitive tests that are absent in most intelligence test batteries. The most notable one is social cognition. Psychologists have been trying to measure it for as almost as long as intelligence, the first being Hunt’s six part test in 1928:

Six parts measuring different factors in social intelligence are included in the test.

1. Judgment in Social Situations, in which the individual taking the test is presented problems in social relationships, and for each, four suggested solutions from which he must choose one.

2. Memory for Names and Faces, in which a dozen faces and names presented at the beginning of the test must be identified later in a larger group.

3. Recognition of Mental States from Facial Expression, in which the mental states must be recognized from the expressions as portrayed in pictures.

4. Observation of Human Behavior in the form of a true-false test.

5. Social Information in the form of a true-false test.

6. Recognition of the Mental States Behind Words in which the individual taking the test must recognize the mental states behind various quotations from literature and current speech.

The correlations between the six parts are all positive, though not strong.

The correlation between social intelligence as measured by this test and IQ is about 0.5.

The scores employees were given on social intelligence tests also correlated highly with ratings their managers gave on how well they dealt with people:

Hunt found the correlation between-social intelligence scores and rating by a superior executive (who had good opportunity to know their ability in dealing with people) for 98 employees in a large sales company to be .61. Of those making above average scores, 75% were above average in ability to get along with people as rated by the judge, and of those making below average scores 77% were below average on the rating.

Most people would take the strong correlation between social IQ and normal IQ as evidence that the social intelligence test does not measure social cognition, but something else, like a test-taking specific ability. I don’t agree with this interpretation; I will go through several other attempts to measure social cognition to explain why.

The reading the mind in the eyes test was another attempt to measure social cognition, which correlates at about .4 with IQ. In this case, it’s difficult to judge if this is due to the fact that the test requires people to know the definitions of emotions that are assigned to the faces.

For what it is worth, autistic people score about a standard deviation below neurotypical people on this test, indicating that it the test measures social cognition to some extent.

The ‘comprehension’ test in the Weschler is often assumed to measure reading comprehension, but really, it attempts to measure common sense and social accumen. In this test, participants are asked questions on the lines of what the function of taxes are, or what should be done when they find a lost wallet on the street. They are then are graded on how well they understand those concepts. Autistics score an average of seven points on the comprehension subtest, a standard deviation below the population mean.

Despite their issues, I think it’s fair to conclude that the results of these studies are accurate, and that social cognition correlates with g at about 0.4 (note: this means it is one of the least g-loaded cognitive abilities). It is true that social settings are fluid and test settings are structured, that social judgement is immediate and not considered, and that the interpretation of cues like body language or voice is difficult to test; that said, knowing the definitions of word, reading comprehension, mathematical ability, the ability to properly rotate objects in the brain, the ability to remember digits, fast reaction time, and being able to do simple tasks quickly all correlate with g. Social cognition not correlating with g at all would make it a massive outlier.

Besides ignoring social cognition, one blogger has argued that intelligence tests only contain well-defined problems where everybody can agree on a correct solution, but not poorly-defined ones, such as who the best political candidate is or what the best way to live life is:

Just like those lines, I think all of our various tests of intelligence aren’t as different as they seem. They’re all full of problems that have a few important things in common:

There are stable relationships between the variables.

There’s no disagreement about whether the problems are problems, or whether they’ve been solved.

There have clear boundaries; there is a finite amount of relevant information and possible actions.

The problems are repeatable. Although the details may change, the process for solving the problems does not.

I think a good name for problems like these is well-defined. Well-defined problems can be very difficult, but they aren’t mystical. You can write down instructions for solving them. And you can put them on a test. In fact, standardized tests items must be well-defined problems, because they require indisputable answers. Matching a word to its synonym, finding the area of a trapezoid, putting pictures in the correct order—all common tasks on IQ tests—are well-defined problems.

[…]

This is why the people who score well on intelligence tests and win lots of chess games are no happier than the people who flunk the tests and lose at chess: well-defined and poorly defined problems require completely different problem-solving skills. Life ain’t chess! Nobody agrees on the rules, the pieces do whatever they want, and the board covers the whole globe, as well as the inside of your head and possibly several metaphysical planes as well.

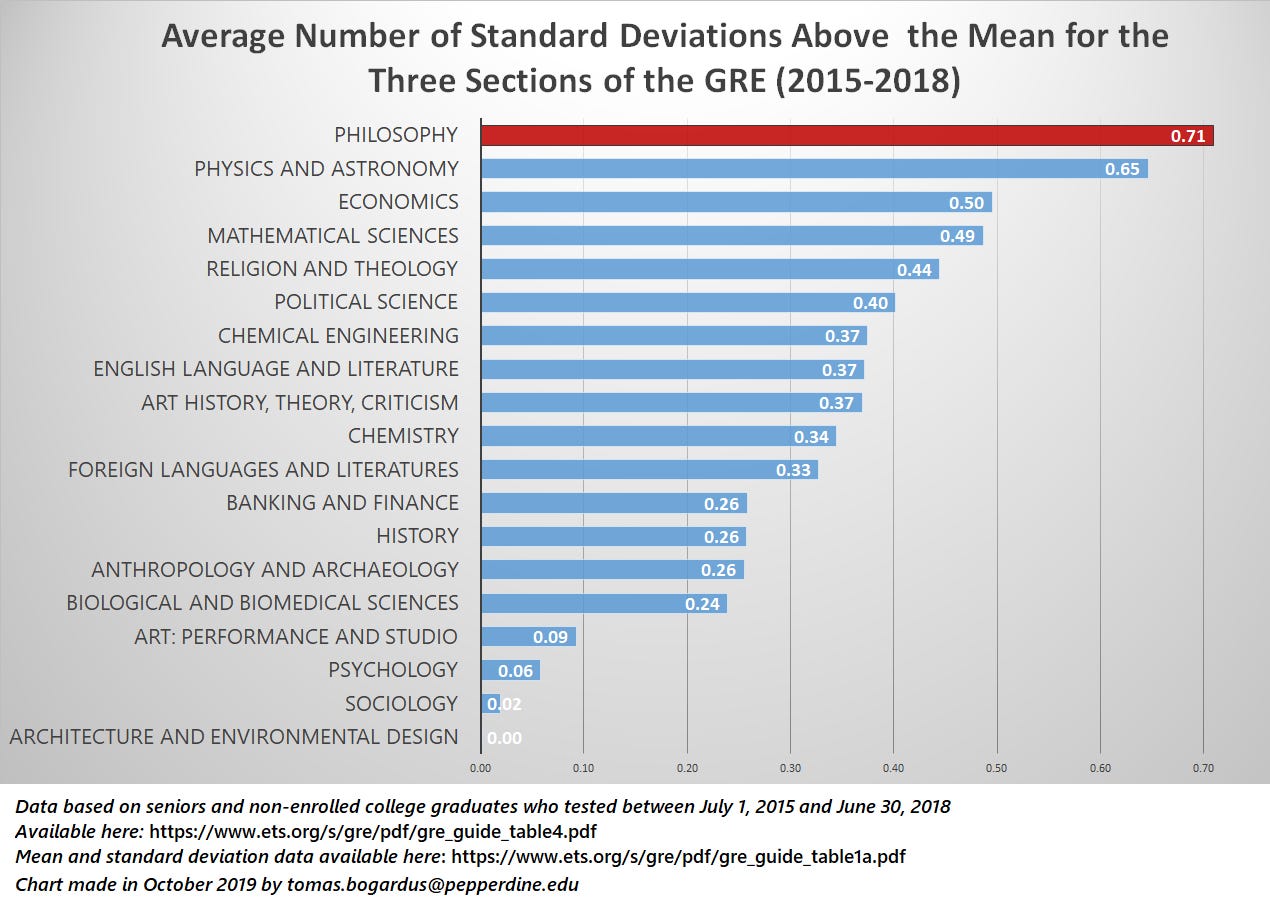

The counterexample I will use here is philosophy, which deals with the most poorly defined questions in the world, such as the nature of morality and the existence of free will. Yet, philosophy students are among the best performers on the GRE, a test used to select graduate students in the United States. Philosophy students do not just do well on reading or writing tests: despite little formal mathematical training, philosophy graduates also rank 14th out of 44 on the quantitative reasoning section.

Most philosophy students probably aren’t good philosophers, but the self-selection effect should be strong enough to the point that philosophy students are better at answering poorly defined questions in comparison to the general population. If it was the case that the ability to answer poorly-defined and well-defined questions correlates weakly, then you would expect philosophy students to not be strong performers on cognitive tests, yet they are, implying the theory is probably false.

This case collapses further when you remember that many top philosophers were also great scientists and mathematicians. In Human Accomplishment, the top 5 philosophers in terms of eminence are Aristotle, Plato, Kant, Descartes, and Hegel. Of these, Aristotle was a biologist and Descartes was a mathematician.

High status philosophers disagree on poorly-defined questions despite being high in g, but the quality of an answer to a poorly-defined question like whether morality exists isn’t so much the answer itself, but the rigor and aesthetic of the answer itself. A low IQ individual might be able to tell you that morality is fake, but would not give a well-reasoned and argued answer for why, but a high IQ individual would be able to give a more complete answer.

Test-taking ability

A golden rule of cognitive traits is that if a trait exists, people will differ in it. So, it should be expected that some people will know how to game cognitive tests better than others. However, the idea that the ability to take tests is independent of general intelligence is unreasonable; surely intelligent people would learn test-gaming strategies faster than others.

Beyond this theoretical issue, there are some cognitive subtests that are very difficult to game. It’s not clear, for example, how a vocabulary test or general knowledge test can be gamed by knowing how to take tests. Guessing the definitions of words, or the locations of cities is not something that can be done reliably. Despite being practically ungameable, these subtests are just as g-loaded (.74 for vocabulary, and .65 for information) as the ones that are gameable.

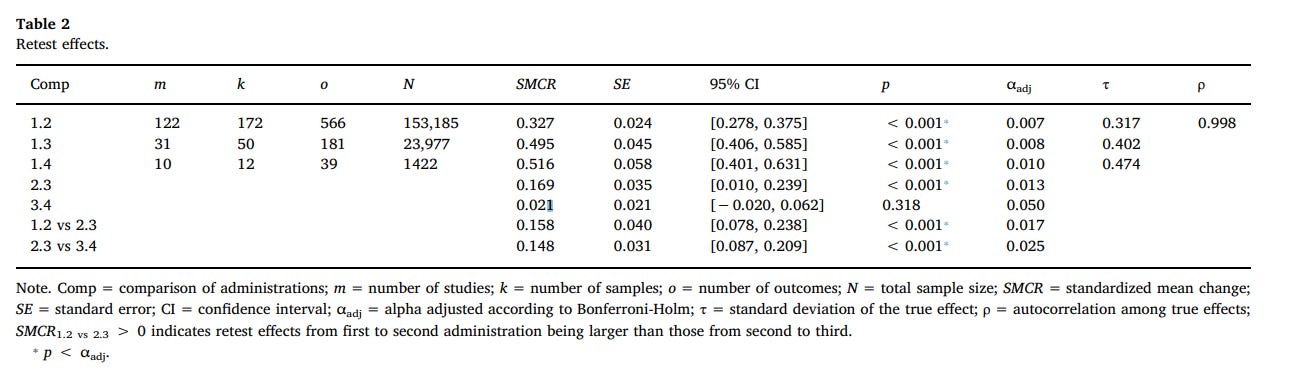

It’s also possible to evaluate the extent to which test-taking is learnable by having people retake IQ tests. If IQ tests are contaminated to a large degree by test-taking ability, then there should be large gains to be made from exposing people to the testing format. After retaking IQ tests, people’s scores on them increase by about 4.5 points on the first retest, 2.5 points on the second retest, and close to 0 points for the third retest — which is not negligible, but not high either.

Out of all criticisms of the ability of IQ tests to measure intelligence, I consider this to be the most plausible one, despite my conceptual criticisms of it. It’s become increasingly difficult to explain why the Flynn effect exists; some have begun to argue that it’s due to increases in test-specific performance, and I find it hard to disagree.

Universality

Intelligence is a perennial concept, though the measurement of intelligence itself is a modern phenomenon, starting in England with Galton. This clearly does not mean that intelligence cannot be tested in other places, though I’m sure that people have made this argument before. Empirically, the observation of a general factor of intelligence has been seen in 31 different countries and even in non-human animals, so the existence of g cannot be dismissed as Anglo-specific.

This does not necessarily mean that the tests themselves are unbiased. Traditionally, test bias is tested for by regressing an unbiased predictor variable onto test scores within two groups, and observing if the slopes or the intercepts differ. Here are two examples of tests of this hypothesis:

In both cases, any slope and intercept bias, if statistically significant at all, is negligible. Jensen summarized the results of these studies in his book Bias in Mental Testing and concluded that mental tests were not biased across racial groups. Since then, it’s been unfashionable in the intelligence research community to believe that IQ tests contain a large racial bias.

Country-level bias is a little more complex; unfortunately, there’s little high quality research on the topic, so it’s difficult to make a definitive conclusion on the matter. I wrote on this topic at length in a preprint; I think there is some bias, but that it cannot explain the massive differences in performance that are observed internationally.

Due to the large differences in group factors of intelligence between sexes, it’s impossible to make an IQ test that has zero sex bias in composite scores. Men do well in general knowledge and spatial reasoning tasks, and women perform better in reading comprehension and processing speed. Fortunately, most IQ test batteries in adults only have a small male advantage, indicating that it is not much of an issue.

Text anxiety

“If you are too anxious to think on a test, how will you be able to think in the real world?” — is what I would say about test anxiety in the real world, partially as a joke but also as a rebuttal. Here I have time to reflect and research, so I might as well take advantage of it.

Empirically, intelligence and test anxiety correlate at -.2 or -.3 depending on the meta-analysis consulted. Add in some generous corrections for unreliability and the true correlation could be close to -.4 or so.

This is not only due to test anxiety causing poor performance, but people being aware of their performance on cognitive tests, and that performance being causal for anxiety. This can be inferred from the fact that the relationship between test anxiety and performance is stronger when anxiety is measured after the test has been taken in comparison to before.

There is also no observed relationship between test anxiety before testing and performance when controlling for anxiety after taking the test. I am very reticent to conclude that anxiety has zero effect on cognitive performance, but it clearly cannot account for why some people have higher IQ scores than others; IQ tests are not anti-neuroticism tests.

Effort

If somebody signs up to take an IQ test, checks zero boxes, and walks out, they will have an extremely low measured IQ. But it is unlikely said score corresponds to their true level of intelligence. So it would be kind of insane to think that the amount of effort somebody puts into a test is completely unrelated with how well they perform. It’s really a question of how much effort biases scores.

There is a meta-analysis on the topic of effort and cognitive test scores, which finds that incentives increase IQ scores by 0.64 SD on average. With a catch: some of the studies they included were fraudulent. Which is not a big deal in the abstract; it’s inevitable that a large meta-analysis will include fraudulent research. The issue is that the fraudulent studies they included are massive outliers and skew the overall effect size.

Bates and Gignac have since conducted a study that finds that the overall effect of incentives on test performance is much smaller than previously reported (d = .16, n = 1201) and was not statistically significant in any of the individual samples they tested the hypothesis in. The correlation between self-reported effort and measured IQ was .28 (n = 3k). Even if generous assumptions are made, one cannot conclude from this evidence that IQ tests are just effort tests.

Conclusion

Most of the proposed issues that have been raised against IQ tests, such as test anxiety, confounding with effort, and test-specific ability are probably that not much of an issue. Although it’s difficult to tell what exactly the true correlation between an IQ score and intelligence is, it’s probably somewhere in the .7 to .9 range — high but lower than most intelligence experts would think it is.

Edit 1: I improved the wording of the article, and some of the argumentation. No big mistakes were made.

Edit 2: 2nd round of wording changes.

By gaming a verbal IQ test, you'd be demonstrating that you deserve the "gamed" score because you'd have to remember vast amounts of information, have a deep enough understanding to define it to the one testing you/find the correct answers if the task involves reasoning, and demonstrate that you have the intellectual curiosity to do this in the first place. I'm sorry you got doxxed bro

Great summary. One thing I think should be examined more on this topic is the existence if individuals who do not match the positive manifold pattern. If we find subsets of people who have out of sync test scores then it tells us a bit more about whether g is a real thing or a statistical thing. Do you know of any studies that explore this? An analogy for this might be that a computer built of parts from the same year will show a positive manifold of performance of the various parts even though there may not be a true underlying computer g that is of the same magnitude. What the underlying cause is is the year each of the parts were built and put together. Similarly a brain might be built of various parts of similar quality and this will increase the seeming singular underlying thing causing it? This is not a argument against g but rather a query about the underlying nature of it or at least it's strength.