TL;DR: students with extremely impressive, hard to fake achievements (e.g. chess grandmaster or skipping 3 grades) should be prioritized. After that, selecting for intelligence using test scores or GPA would be the most effective method of getting the most competent student body. Everything else (assessments of character/personality from personal essays, leadership, volunteering, extracurriculars, interviews) is worthless.

The first things that come to mind are GPA/SAT/ACT scores, which are not that predictive, so intuitively it makes sense to select based on variables like essays, recommendations, or interviews… Which would be a good idea if any of these methods worked.

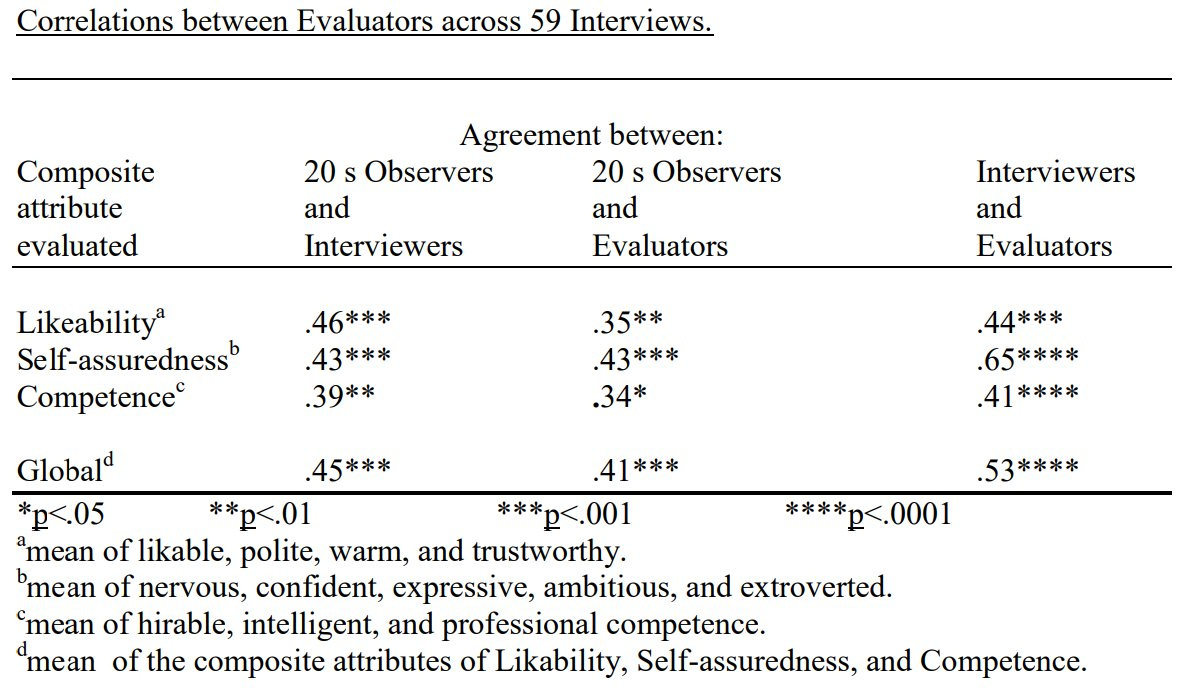

Unstructured interviews don’t work because raters cannot agree on how to rate the candidates. On average, interviewers agree at about .45 when it comes to assessments of traits. And there is no guarantee that the traits that cause them to give consistent ratings are ones that are actually valuable.

And neither do references for that matter.

Besides the issues with interviews, nonacademic ratings suffer from the fact that they simply have little predictive validity. The following data I cite is from this excellent study which examines the effects of attending highly selective Ivy-Plus universities (Ivy league schools + MIT + Duke + Stanford + UChicago):

Abstract:

Leadership positions in the U.S. are disproportionately held by graduates of a few highly selective private colleges. Could such colleges — which currently have many more students from high-income families than low-income families — increase the socioeconomic diversity of America’s leaders by changing their admissions policies? We use anonymized admissions data from several private and public colleges linked to income tax records and SAT and ACT test scores to study this question. Children from families in the top 1% are more than twice as likely to attend an Ivy-Plus college (Ivy League, Stanford, MIT, Duke, and Chicago) as those from middle-class families with comparable SAT/ACT scores. Two-thirds of this gap is due to higher admissions rates for students with comparable test scores from high-income families; the remaining third is due to differences in rates of application and matriculation. In contrast, children from high-income families have no admissions advantage at flagship public colleges. The highincome admissions advantage at private colleges is driven by three factors: (1) preferences for children of alumni, (2) weight placed on non-academic credentials, which tend to be stronger for students applying from private high schools that have affluent student bodies, and (3) recruitment of athletes, who tend to come from higher-income families. Using a new research design that isolates idiosyncratic variation in admissions decisions for waitlisted applicants, we show that attending an Ivy-Plus college instead of the average highly selective public flagship institution increases students’ chances of reaching the top 1% of the earnings distribution by 60%, nearly doubles their chances of attending an elite graduate school, and triples their chances of working at a prestigious firm. Ivy-Plus colleges have much smaller causal effects on average earnings, reconciling our findings with prior work that found smaller causal effects using variation in matriculation decisions conditional on admission. Adjusting for the value-added of the colleges that students attend, the three key factors that give children from high-income families an admissions advantage are uncorrelated or negatively correlated with post-college outcomes, whereas SAT/ACT scores and academic credentials are highly predictive of post-college success. We conclude that highly selective private colleges currently amplify the persistence of privilege across generations, but could diversify the socioeconomic backgrounds of America’s leaders by changing their admissions practices.

[…]

2 Data

We construct a de-identified dataset on parent characteristics and student outcomes by linking five sources of data: (1) federal income tax records on parents and children’s incomes from 1996-2021; (2) 1098-T tax forms on college attendance from 1999-2015; (3) Pell grant records from the Department of Education’s National Student Loan Data System from 1999-2013; (4) standardized test score data from the College Board from 2001-2005 and every other year from 2007-15 and ACT from 2001-15; and (5) applications and admissions records for undergraduate first-year student admissions spanning subsets of years from 1998- 2015 from several Ivy-Plus colleges and highly selective public flagship universities, as well as data for all colleges in the University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) systems and all four-year public colleges in Texas from the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board (THECB). We include data from UC-Berkeley, UCLA, and UT-Austin among others in our sample of highly selective public flagship universities with internal data. These five sets of data were linked to each other at the individual level by social security number and/or identifying information such as name, date of birth, and gender.8

They tracked many of the student’s characteristics, such as their academic ratings, nonacademic ratings, earnings, and test scores. Nonacademic ratings predicted reaching the top 1% in earnings after graduating, but this effect disappears after controlling for the effect of attending selective universities.

Nonacademic ratings did not predict attending elite graduate schools or prestigious firms.

Test scores, however, did predict achievement in this sample, even after controlling for attendance, race, gender, and GPA:

Given that there are no threshold effects for cognitive ability, it should be expected that high scores exhibit no threshold effects. This appears to apply to SAT scores, but not GPA.

As nonacademic ratings assessed by admissions departments don’t predict anything, my priors are that most conventional selection methods (e.g. volunteering, extracurriculars, interviews, personal essay ratings, references) do not work, which corroborates the results from Hunter and Schmidt’s meta-analysis of predictors of job performance. I’m not sure if this is the case for athletics, thougy — they’re a decent signal of a prosocial and functional personality.

III.

There are other methods of evaluating students besides everything that I brought up earlier, such as extreme levels of achievement: skipping grades, winning national competitions, or high elo in chess. Hard to fake signals of extreme competence and intelligence should be considered the gold standard when it comes to admitting students to elite universities. Stuff like businesses or starting nonprofits can easily be faked using parents or friends.

After admitting these students, the next priority should be selecting for high GPA/test scores.

An experimental strategy for elite universities could be selecting for old money: this is not a good idea from an optical point of view, but I think it could work pretty well. Because regression to the mean happens once, this means that selecting for social class itself would not be effective, as there is a chance that the parents of the child succeeded due to environmental factors or non-additive genetic effects. Old money is a little different — if a lineage has managed to stay wealthy for a long time, then that perhaps speaks to their genetic quality. Or to a large inheritance that is well-managed. Who knows.

Asians and men should be discriminated against at elite universities — this is because a sex ratio of 50-50 is ideal for social purposes, and because Asians exhibit lower levels of eminence (e.g. extreme wealth, creative achievement) in comparison to what would be predicted from intelligence alone.

#######################################

This post was motivated by the story of an Asian student who had a 97.3% GPA average, multiple extracurriculars (captain of NYC math team, volleyball player, and Jazz musician), and a 1560 SAT score who got rejected from many universities went viral recently. Responses to the story were quite polarized — some said he was trying too hard and deserved the rejections, others said it was an unfortunate incidence of universities discriminating against Asians.

From an objective standpoint, this is clearly a very impressive student. A 1560 on the SAT corresponds to the 99.75th percentile relative to the nation; in IQ notation that would correspond to a score of 142. He also has the close to perfect GPA, in one of the most competitive high schools in New York. Most people with this SAT score are not fantastic students because of regression to the mean, as SAT scores and GPA only correlate at .45. I’d guess that, in terms of latent academic aptitude, he would be about 3 to 4 standard deviations above the mean relative to American students. If admissions to Ivy league universities were only based on academic ability, then he would probably get in.

The average IQ of harvard students is definitely higher than 122, there are some factors that attenuate the IQ observed in this study, the sample is mostly composed of psychology students, ceiling effect, they used the abbreviated WAIS which obviously has a lower g-loading than the full WAIS and I'm not sure if it's right to correct for the flynn effect in this case.

Taking all this into account, the average IQ of Harvard students should be around 130.

"and men should be discriminated against at elite universities — this is because a sex ratio of 50-50 is ideal for social purposes"

Why exactly? For the purpose of increasing the likelihood of high IQ men and women having children with each other? I don't see any other reason.