People have preferences.

Some states of affairs are more consistent with those preferences than others.

Those states are independent of the preferences of any one person.

“Morality” (here defined as a rule or action that contributes to a better state of affairs) is therefore objective.

All other theories of ethics are dysfunctional: deontology is arbitrary, natural law is for the religious, and the social contract is an illusion.

The caveats I mentioned earlier?

In practice, ethical behaviour is a signalling mechanism, not a utility maximization mechanism.

There is nothing that obligates people to act morally.

Social communities praise those who behave in accordance with morality, so some people take advantage of that and behave in ways that are endorsed by the community. The paradox of people thinking they are deeply moral people can be reconciled with the Nietzschean/Hansonian self-deception paradigm: a ruse is most effective if the ruser is convinced that no ruse is occurring.

It is easy for utilitarianism to become hijacked by people who want to optimize for something else — e.g. socialists who only care about the weak claim their policies are for the greater good, while libertarians advocate that their policies would lead to more economic growth for everybody. I blame this largely on the fact that the concept of the “greater good” is nebulous and difficult to measure.

Would nuking all of civilization be for the greater good? The answer may seem intuitively obvious, but you could make a reasonable case that it could be for the best. What about war? It kills a lot of people. It’s scary. But it also makes civilizations try hard to optimize for something and gives people a grander purpose in life.

This nebulous status of the greater good is why people advocating for their own interests works — most people are introspective enough to know what is good for them, at least to some degree. There are some obvious situations like broadcasting the torture of a child where there is clearly little to be gained, otherwise the greater good is difficult to understand.

Effective Altruism

Effective Altruism (EA) is a cult movement that tries to employ science and reason to maximize value around the world. Despite my inclination towards utilitarianism, I do not support them for two reasons: humans are too selfish for a mass altruistic movement to work and the causes they focus on are inappropriate.

Take their frontpage as an example:

Right now, their main causes are focusing on preventing AGI doom and donating to charities. Charities that send aid to the poorest places in the world in particular are bad because they exist to expand structures that are disfunctional, not to make them functional. If foreign aid was able to lift the poor out of poverty, it would not be called aid, it would be called something else: loans and investments.

Their push against factory farming is cool, though I do not think they will accomplish much. Legislation in this area is notoriously stubborn.

Of the issues that they tackle, the only one that is right wing coded is charter cities — I concede that the EA people have been remarkably stubborn in their support for PRAXIS, despite the fact that it is overtly right wing. There are many other right wing causes that they could support: eugenics, deregulation (with the exception of housing), obesity prevention, researching microplastics, and banning toxic pesticies and additives. The problem is that they do not want to advocate for them because they are either libtards (so not they are not altruists) or because they do not want to signal being right wing (still not altruists).

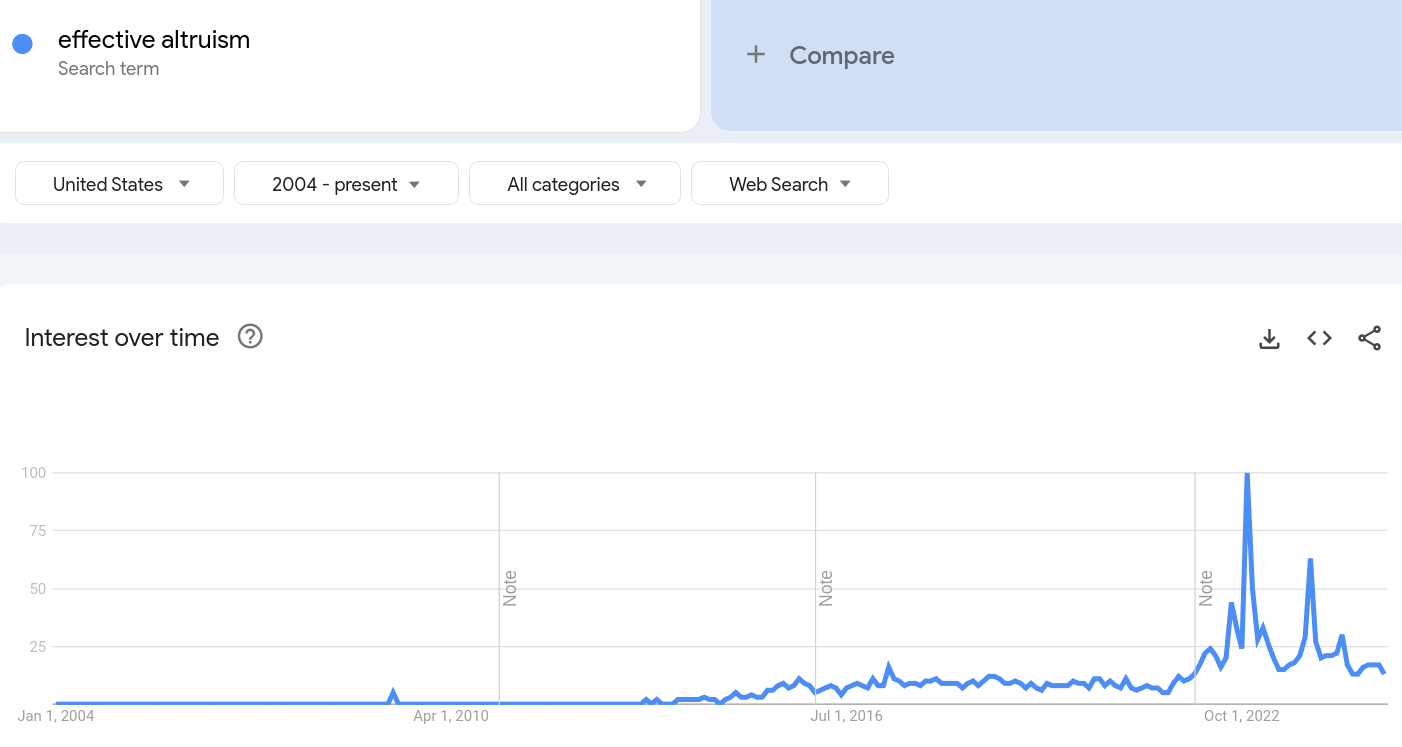

On a side note, the movement is likely dying soon.

Slave morality?

Whether or not utilitarianism is “slave morality” was the initial disagreement that set off the Walt Bismarck and Bentham bulldog beef, which spawned the most hilarious article header I have ever seen.

Scott Alexander also published on the topic, arguing that liberal utilitarianism is not slave or master morality, but a compromise between the two, and that Hanania/Yglesias as thinkers most imitate Nietzsche. An ultimately wrong take.

In Nietzsche’s philosophy, slave morality and master morality are negative ideas; the purpose of them is to deconstruct people’s conceptions of right and wrong, not to advocate for any particular system of morality, be it master or slave. Whether or not utilitarianism is “slave morality” is not really relevant to Nietzsche; what he critiques is morality itself. The man himself considered utilitarianism to be vile and slavish.

I see no reason why, in theory, utilitarianism could not accomodate for the fact that some people are much more valuable than others. In practice, utilitarianism devolves into people’s genetic morality or is a front for the interests of a particular group because of the hazy nature of the greater good as a concept, so I don not mind the fact that the theory is rejected by many. But in practice, most people can’t really be 100% cynical amoralists who have zero political opinions because they only care about what is in their best interests, and so they will need to have some kind of framework by which to judge what is better and worse. For me, that is utilitarianism, and I see it as the only valid method by which to do this.

So I guess you could call utilitarianism an infohazard: something that is true, but if believed by the masses, causes them to want to donate 20 trillion dollars to Africa.

I identified as a utilitarian for most of my life but stopped after SBF.

My main critique of utilitarianism is that as an ideology it is criminogenic. EA generated at least three crypto criminals over a one year period and SBF himself was the child of two utilitarian philosophers. The odds ratios here are undeniable.

I don’t really know what you do with that, but it’s made me more sympathetic to folk skepticism around it.

If I had a dollar for every time someone read Neitzsche, and came away with the wrong conclusion that master morality is 'good' and slave morality is 'bad', well...

(Americans, in particular, seem highly predisposed to a moralistic worldview, that is to say making moral lenses on society primary.)