Cultural drift a phenomenon where natural selection on ideas between regions is relaxed, so forces within a society determine its culture. A simple example: society antenatal hates children and instructs their members to not procreate, and their neighouring society progenesis instructs all of their members to have children. After 40 years, progenesis takes over antenatal’s land once their population collapses. In the modern world, the revealed preference of anti-natalism would be an example of cultural drift, where nations have shifted in one direction without any outside influence or natural selection at bay.

Now, comes obesity. On a diet of rice, wheat, dairy, and meat, it’s difficult for European and Asian peasants to get fat, especially when they live at subsistence levels and work long hours. Any person who would become visually overweight would stick out like a sore thumb, so there was quite a bit of social pressure to stay thin even beyond the environmental difficulties. And any society that, for whatever reason, adopted social norms that permitted obesity, would be out-competed by those who suppress it.

Some think that cultural forces are largely responsible for suppressing obesity; in some cases, this is correct — there is evidence that televisions alter people’s perceptions of what body types are ideal, and that, in Nicaragua, regions with more access to televisions also have more women dieting. But there are also other cultural forces that are responsible for increasing the social acceptability of obesity: namely, the fact that there’s simply more fat people, so fat shaming becomes less prevalent and effective at reducing obesity. Cthulhu typically swims left, and since body positivity is left wing, it will swim there.

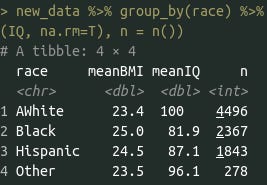

Within countries that are already modernized, there are substantial differences in obesity rates between countries: highest in Blacks, followed by Arabs, Hispanics, Whites, then Asians.

This follows the traditional IQ rank order — so it’s easy to chalk the differences up to intelligence. The issue is that, within the same country, intelligent people tend to have lower weights relative to heights, but the association is very weak (r = -.1).

Every unit of IQ is associated with a decrease in BMI by about -.033, a decrease that is not sufficient to explain the race differences in obesity — within this sample, Hispanics have BMIs one point above Whites, but have IQs that are only 13 points lower, so the IQ difference only explains half of the obesity difference. And this ignores that part of the reason why obesity and IQ are associated is because of the group differences — regressing IQ and race onto BMI hardly changes the race differences in BMI, but it shrinks the relationship between IQ and BMI by about half (regressions in Appendix).

Also, the association between IQ and BMI does not hold up within families:

We used data from four United States general youth population cohort studies: the National Longitudinal Study of Youth 1979 (NLSY-79), the NLSY-79 Children and Young Adult, the NLSY 1997 (NLSY-97), and the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS); a total of 12,250 siblings from 5,602 households followed from adolescence up to age 62. We used random effects within-between (REWB) and residualized quantile regression (RQR) models to compare between- and within-family estimates of the association between adolescent cognitive ability and adult BMI (20 to 64 years). In REWB models, moving from the 25th to 75th percentile of adolescent cognitive ability was associated with −0.95 kg/m2 (95% CI = −1.21, −0.69) lower BMI between families. Adjusting for family socioeconomic position reduced the association to −0.61 kg/m2 (−0.90, −0.33). However, within families, the association was just −0.06 kg/m2 (−0.35, 0.23). This pattern of results was found across multiple specifications, including analyses conducted in separate cohorts, models examining age-differences in association, and in RQR models examining the association across the distribution of BMI. Limitations include the possibility that within-family estimates are biased due to measurement error of the exposure, confounding via non-shared factors, and carryover effects.

I find this very hard to believe, and assume it’s just a power failure. But the fact that the association declines when comparing people in the same family is not debatable.

So, my theory is as follows. Highly intelligent groups of people have stronger preferences for people who are fit (in dating, employment, and whatnot), so people in these groups are more likely to try to lose weight. Because of this, the cultural drift towards higher levels of obesity is weaker within intelligent groups, despite the fact that the rate at which they lose weight is barely linked to how intelligent they are. I have no quantitative evidence that suggests that intelligent people have stronger preferences for fitter partners, but there is a lot of indirect evidence for it. Preferences for slimmer women follow the familiar racial rank order, and they are also correlated with social class.

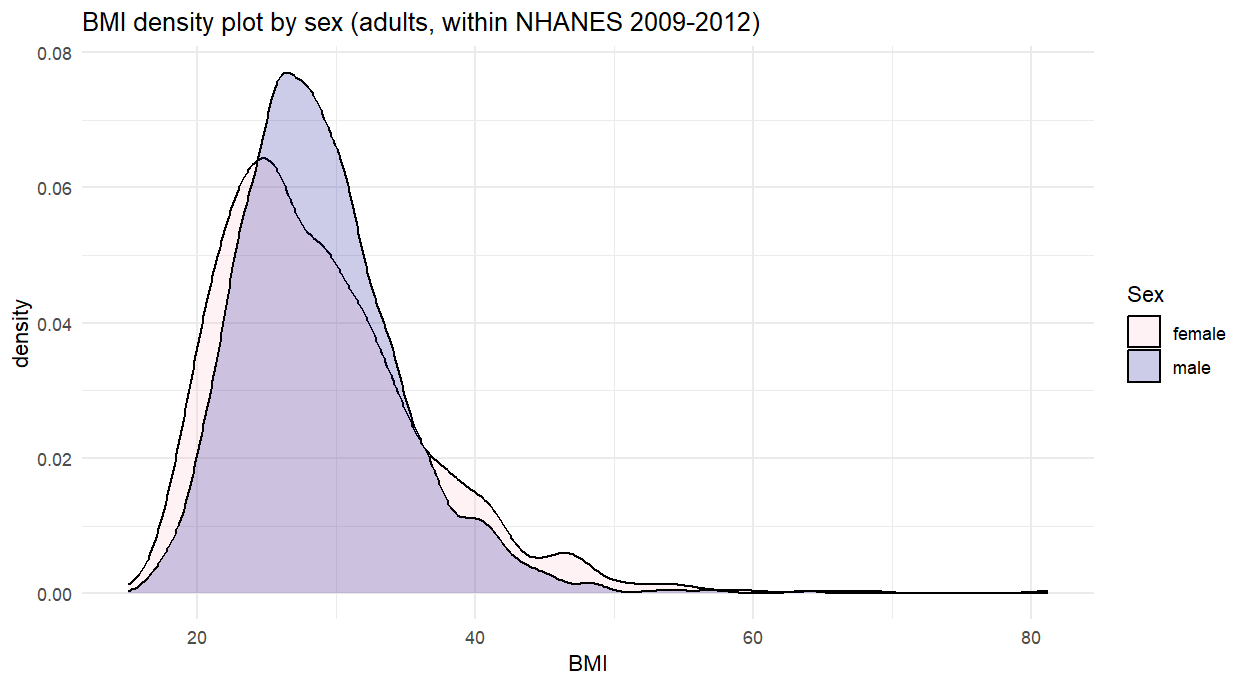

There also appears to be an interaction between being a woman and IQ when predicting BMI — the relationship is nonexistent within men, but negative within women, even after controlling for race and parental SES.

The interaction also exists at the national level. Countries with higher IQs tend to have more overweight men than women, while the opposite is the case for low IQ countries.

The greater variance in female BMI is also consistent with a cultural explanation, where culture has greater effects on women’s BMI, so it causes it to vary more.

This also explains why cross-national obesity correlations don’t pick up on very much besides identifying which countries have modernized more: the rate of cultural drift between countries differs — this seems to correlate somewhat with national IQ, where more intelligent countries have lower levels of obesity independent of development, but even past that there is substantial variation: France and the USA are about equally intelligent, but have large differences in obesity rates.

Appendix

> Now, comes obesity. On a diet of rice, wheat, dairy, and meat, it’s difficult for European and Asian peasants to get fat, especially when they live at subsistence levels and work long hours. Any person who would become visually overweight would stick out like a sore thumb, **so there was quite a bit of social pressure to stay thin even beyond the environmental difficulties**. And any society that, for whatever reason, adopted social norms that permitted obesity, would be out-competed by those who suppress it.

I think the opposite it's true. Pre-industrial peasant cultures were so poor compared to modern standards than been somewhat plump, specially as a juvenile or a female, was seen as positive and interpreted as a sign of wealth. Some boomers and genX's in southern and eastern Europe still experience their grandmas, who grew up in borderline famine condition, trying to fatten them as children. I'm sure similar experiences persist in younger cohorts in the middle east, India and East Asia.

I was not expecting China to be fatter than India, or for Czech Republic to be one of the fattest countries in Europe.