The Six Political Instincts

Hierarchy, Authority, Lindy, Vetocracy, Sacred, Revolution

The Hierarchical Instinct

Hierarchy is the most important political instinct and it underlies every single political issue, which is why I call it the first general factor of political views. Typically, if one does a factor analysis of political questions, the statistical factor that explains the most variance in answers is the right-left or hierarchy-equality factor — the same things, really.

This factor is called hierarchy instead of equality because I believe that living things, by default, are egalitarian, and that hierarchical tendencies are something that animals become rather than are.

The Authoritarian Instinct

All humans have an authoritarian impulse, though they don’t have them to the same degree, and these impulses coexist with revolutionary ones, vetocratic ones, and even egalitarian ones. Humans with revolutionary impulses will feel an authortarian impulse towards their leader, while the vetocracy answers to the committee. Egalitarians prefer to answer to each other, though, due to the iron law of oligarchy, they inevitably choose a leader. This is why hierarchical and authoritarian impulses tend to correlate within humans, despite not being the same thing.

The Lindy Instinct

It’s easy to conflate this instinct with authoritarianism or being right wing. But it’s very different. There are a lot of people who are averse to genetic engineering and ozempic who aren’t hostile to homosexuality, for example. Liking tried and tested things is its own thing besides liking hierarchy or religion. While it is more present in right wingers and authoritarians, the instinct also emerges in left wingers in the form of environmental advocacy and climate change activism.

The Vetocratic Instinct

The vetocratic instinct (an idea I stole from Vitalik) causes humans to make decisions that are less risky and trend towards deciding by consensus. This expresses itself in different ways, depending on the other instincts: in right wingers it manifests itself as a disposition towards zoning laws and private property, while in left wingers in manifests as support for human rights and regulation.

I hypothesize that this instinct is anticorrelated with the hierarchical instinct and the revolutionary instinct. Egalitarians prefer power to be distributed among the masses, and if that is done, they will naturally chose less risky choices. On the other hand, if power is concentrated in just one person, they are more likely to use it to take larger risks. Assuming that people’s competence is distributed on some kind of bell curve, because of the way t-distributions work, the standard deviation of the mean of a sample with one observation will be much greater than that of one that has three hundred, so political structures that rely on a few people being in power are also inherently riskier over those that rely on voting or some kind of committee.

The Sacred Instinct

Typically, humans prioritize their values and needs according to some implicit hierarchy that is difficult to describe. The sacred overrides this structure, and compels humans to and prioritize a thing above what it would be placed at in their normal structure. In humans, this usually manifests itself as theistic religiosity, though in others, it can manifest itself as a personality cult or as the enforcement of taboos against researching race and genes.

The Revolutionary Instinct

Presumably, prehistoric humans would have some kinds of intergroup conflicts that would lead to status hierarchy shifts. Perhaps if one leader starts to grow senile, or if one turns out not to be as ethical as people thought they were, they would be conspired against and thrown out. Those who joined the revolution survived more than those who didn’t, and thus came this instinct to be.

How this maps out:

I don’t think that political ideologies are rational, that is, they serve political convenience and personal feelings more than logical coherence. Of the 21 ideologies I counted, I consider them to load on the 6 instincts in the following manner:

Allow me to elaborate on my reasoning with a few examples.

Monarchism is hierarchical and authoritarian because it places one person at the top who has a lot of power, it’s lindy because it’s a classic political structure, it’s sacred because people are meant to acknowledge the king as having a divine right to rule, and it’s not revolutionary because it assumes a continuing power structure. It’s not vetocratic or “bulldozey” because the decisions that are made are based on the king’s will — if he wants safety, then it’s safety. If he wants risk, then it’s risk.

Liberalism isn’t defined by anything besides being a type of vetocracy that prevents revolution or rapid change, because anybody is allowed to win as long as they play by the system’s rules.

Some potential challengers to my theory. First, we have the political compass:

So, the obvious two things that they got right are the axes. Besides that, it suffers from low levels of dimensionality — it notably lacks a proper tradition/lindy vs progress/rationalism factor as well as a secular/profane vs sacred/pure factor.

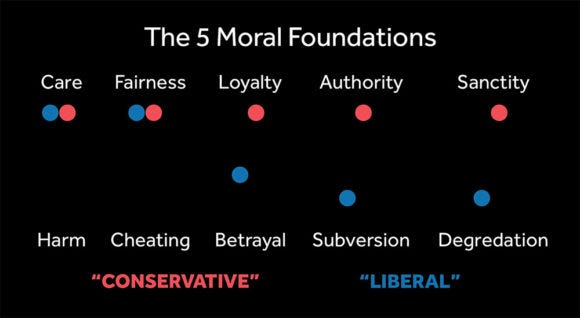

And, we have moral foundations theory.

The main issue here is the loyalty vs betrayal axis. All political movements are structured around the friend-enemy distinction. They just do it in different ways.

The second is the choice of care and fairness — I think hierarchy vs equality condenses these foundations into a more informative and reduced fashion. Consider this: somebody wants humans to be more equal, they might naively try to equalize the rules and environments they live under. Which, if done competently, will actually magnify the phenotypic differences between humans. So they have to settle for a different method of enforcing equality.

Really good. Would love to see a cross-comparison of this with Big 5.

Interesting. Would be curious to hear more about Lindy, not sure I understand it very well. Something about survival? Survival on an individual level?

Btw, side point: the political compass plottings are a bad joke, and it’s worth taking the Political Compass quiz “as Trump” or “as Harris” and see how far you get from where they put the dots.