Why are both recruiters and applicants frustrated with the white collar job market?

credential inflation, inefficient selection, AI, the internet

Two different narratives with regard to the job market pervade on the internet right now: the youth complain about an extremely selective, cutthroat environment where qualified candidates are rejected by default from most jobs, while managers and employers complain about lazy, entitled hires who can’t even print ‘Hello world’ or define what a p-value is even if they have relevant degrees.

Both of these stories may appear incompatible, but there are two theories that explain both of these observations:

Signalling theory of education.

Most mechanisms used to select employees (e.g. interviews) don’t work well.

Signalling theory of education

People with better education have higher incomes, every year of education confers an increase in income of about 8-12%. This can be due to three different factors: education → skill acquisition → income (human capital theory), education → positive productivity signal → income (signalling theory), or education being correlated with skills which cause income (ability-confounding theory, which everybody believes in to some extent).

Economists don’t exactly agree on which factors have a greater role in the relationship, but the bulk of the evidence favours signalling over human capital theory. Several entire books have been written on the subject; the best is Bryan Caplan’s Case Against Education where he lays out the different pieces of evidence in favour of the theory.

The best one is the sheepskin effect, where most of the effect of education on earnings is concentrated on the year that confers the diploma. Statistically, controlling for degree status reduces the effect of years of education on income from 11% to 2.5% in the GSS.

If skill acquisition were the primary reason that educated people earn more money, then you would expect the effect of each year of education to be similar in terms of its effects on income; the sheepskin effect is more consistent with the signalling theory. Presumably some of this reflects ability confounding where people who drop out just before finishing are likely to have mental/emotional issues that prevent them from succeeding in life, though I would note that if signalling theory were not true then people would not be so reluctant to drop out after 6-7 semesters in the first place.

Caplan also details how individuals with humanities/social science degrees (which do not confer job-relevant skillsets) still have higher incomes than individuals who do not graduate from college, which is consistent with the signalling explanation because the existence of their degree still shows that they can put up with academic coursework.

They also have the same incomes regardless of whether they claim to use the skills they learned in university on the job (an admittedly loaded question).

To weigh the power of human capital versus signaling, however, we must zero in on occupations with little or no plausible connection to traditional academic curricula. Despite many debatable cases, there are common jobs that workers clearly don’t learn in school. Almost no one goes to high school to become a bartender, cashier, cook, janitor, security guard, or waiter. No one goes to a four-year college to prepare for such jobs. Yet as Figure 4.1 shows, the labor market pays bartenders, cashiers, cooks, janitors, security guards, and waiters for high school diplomas and college degrees.

In terms of how much each factor contributes to the education~income association, I would peg it to be 15% skill acquisition, 30% signalling, and 55% ability confounding. I lean towards higher estimates of ability confounding because controlling for even imperfect measures of g/skills (vocabulary, math, reading tests) and noncognitive ability (self-perception, perceived teacher ranking) results in the education premium falling by half:

7 When researchers correct for scores on the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT), an especially high-quality IQ test, the education premium typically declines by 20–30%.

8 Correcting for mathematical ability may tilt the scales even more; the most prominent researchers to do so report a 40–50% decline in the education premium for men and a 30–40% decline for women.

9 Internationally, correcting for cognitive skill cuts the payoff for years of education by 20%, leaving clear rewards of mere years of schooling in all 23 countries studied.

10 The highest serious estimate finds the education premium falls 50% after correcting for students’ twelfth-grade math, reading, and vocabulary scores, self-perception, perceived teacher ranking, family background, and location.

Employers are bad at evaluating job performance

One of the traditional objections against signalling theory is that the effect of education on earnings persists in older individuals, meaning that employers never discover the true value of employees, inconsistent with an efficient market. Which is an objection that never really made sense to me, surely it would be more reasonable to evaluate whether employers actually can evaluate performance.

It turns out the inter-rater reliability of supervisor ratings is 0.52, meaning that “latent job performance” only explains about 50% of the variation in supervisor ratings (no need to square as it is a latent factor, not a direct path). A 1996 meta-analysis finds that other attempts to analyse the same statistic have come to similar conclusions:

Accordingly, we are unaware of any evidence that directly contradicts this estimate. In fact, .52 is consistent with previous estimates, including Conway and Huffcutt’s (1997) separate meta-analytic estimate of .50 (k =69, N =10,369); Rothstein’s (1990) asymptotic estimate of .55 (for duty ratings); Hunter’s (1983) estimate of .60; King, Hunter, and Schmidt’s (1980) estimate of .60; and Scullen, Mount, and Sytsma’s (1996) estimate of .45.

One professor from Oregon attempted to study the reliability of interviews using his undergraduate students. He found roughly the same poor reliability:

In the present study, naive observers evaluated the initial greeting that took place within 59 employment interviews. Two trained interviewers conducted each employment interview, which was videotaped. After each twenty-minute interview, the two interviewers completed a post-interview questionnaire evaluating the candidates on their interview performance, behavior, rapport, and professional skills. These evaluations constituted the interview outcome criteria that we attempted to predict. Brief video clips were extracted from the recordings such that each began when the interviewee knocked on the door and ended five seconds after the interviewee sat down. Only the interviewee could be seen on the video. The video clips were shown to naïve observers who rated the interviewees on 12 interpersonal attributes, among these were hirable, competence, and warmth. These judgements were used to predict the outcome of the interview, operationalized as the mean of the two interviewers’ assessments. Naïve observer judgments based on the initial 20-seconds significantly predicted interviewers’ assessments who questioned the applicants for over 20 minutes. The present study showed that a personnel director’s assessment of an applicant’s skill, knowledge and ability might be fixed as early as the initial greeting of the formal interview.

The agreement between evaluators regarding the competence, likability, and confidence of interviewees was low, with reliability coefficients ranging from .3 to .7:

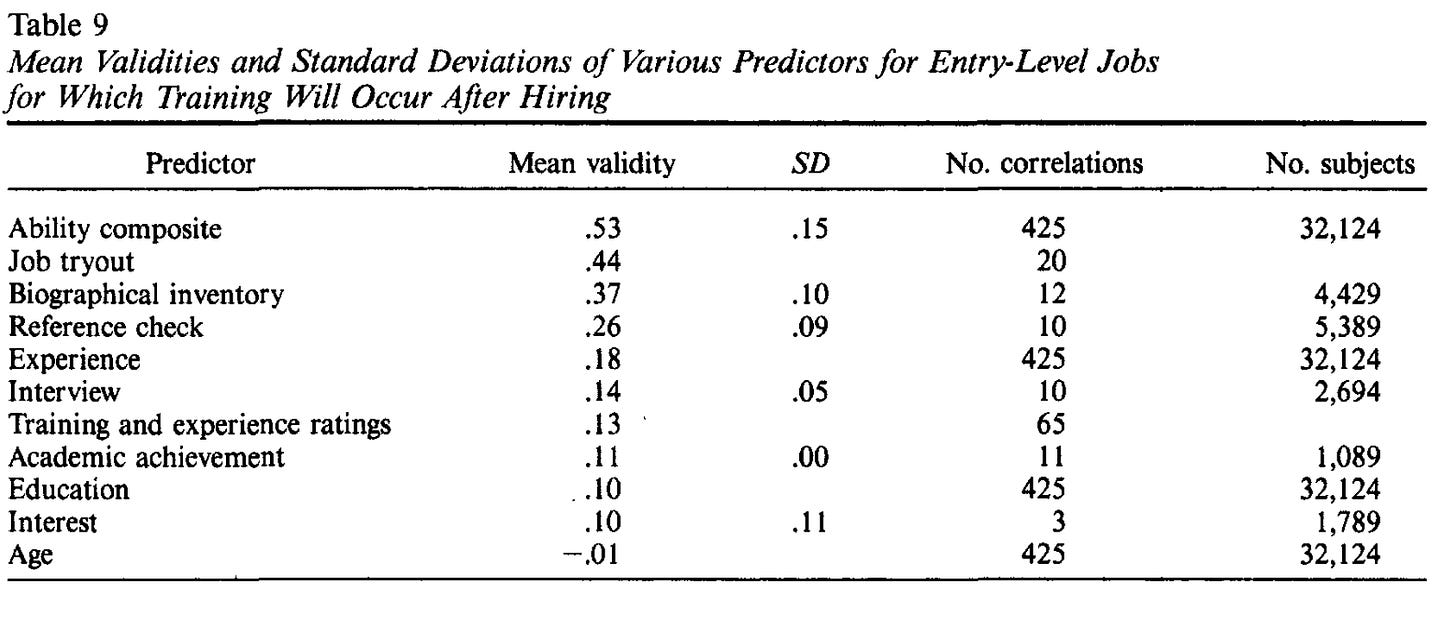

The reliability of a variable acts as a ceiling to its predictive validity, so the true validity of interviews/supervisor ratings is probably lower than it appears. And it is — performance in interviews only correlates at .14 with performance in entry-level jobs. Other typical measurements of competence (biography, references, experience, academic achievement) are not promising.

I don’t “blame” the employers for this per say, as this is also true for any subjective rating of anything. The inter-rater reliability of peer reviewers is .35. The correlation between self-ratings of personality and peer-ratings of personality is .47. I haven’t seen the statistics on this but I assume that ratings for works of art, games, or television series would also be inconsistent between raters. Presumably S-tier entrepreneurs or programmers would be able to rate the competence of interviewees well, but these statistics describe averages, not tails.

Selecting for IQ would also not fix this. The .5 correlation between IQ and job performance that is often cited comes after relevant corrections for unreliability in testing and restriction of range, both of which will be present when evaluating the competence of candidates in a real world setting. Absent these corrections, the correlation between IQ and job performance is typically .2 to .3.

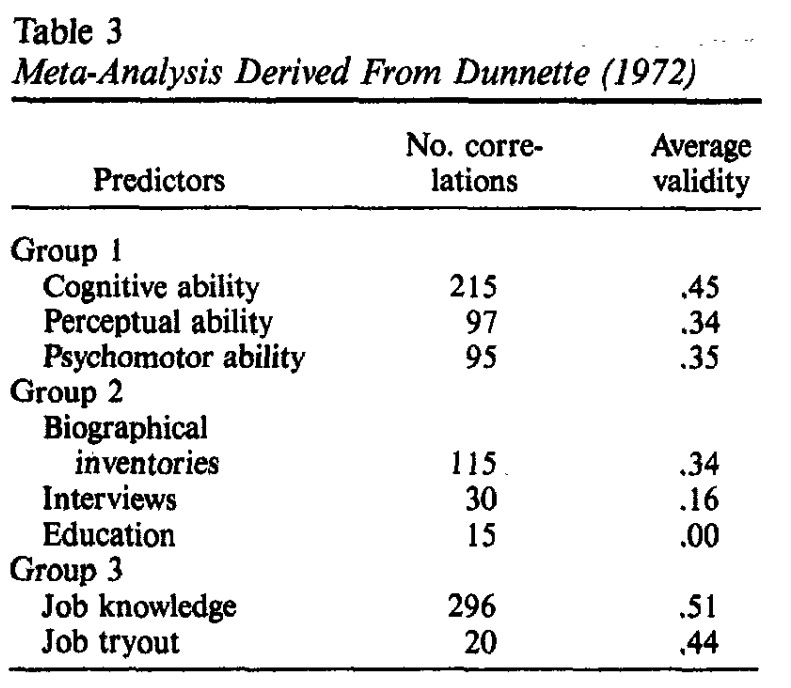

In fact, job knowledge is a superior measurement of ability on the job:

Back on topic

People in the United States (and most countries around the world) have been getting more educated over time. From a human capital perspective, this is good because it means that the skills that are drilled by schools are being gained by a wider audience. From a signalling perspective (and ability confounding perspective, to an extent), this is only means that students have to waste more of their years studying to stand out in the job market.

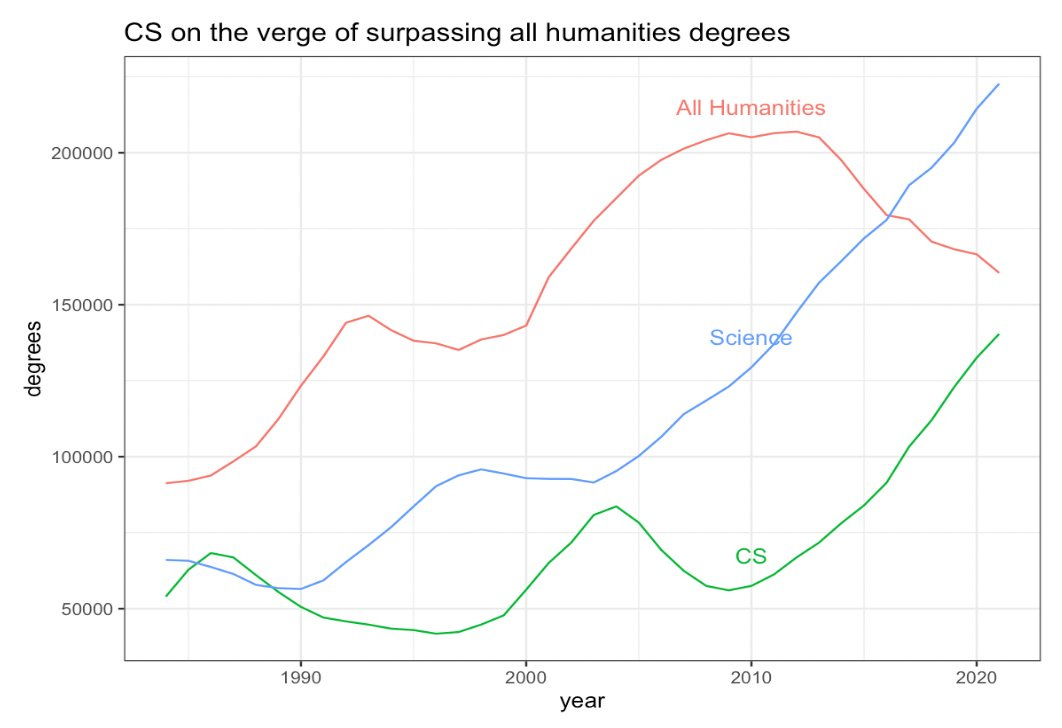

Credential inflation has been particularly awful for STEM, where there are about 3x as many STEM graduates in the modern day as there were in the 80s, while humanities have jumped in size by only 50% over the same time period.

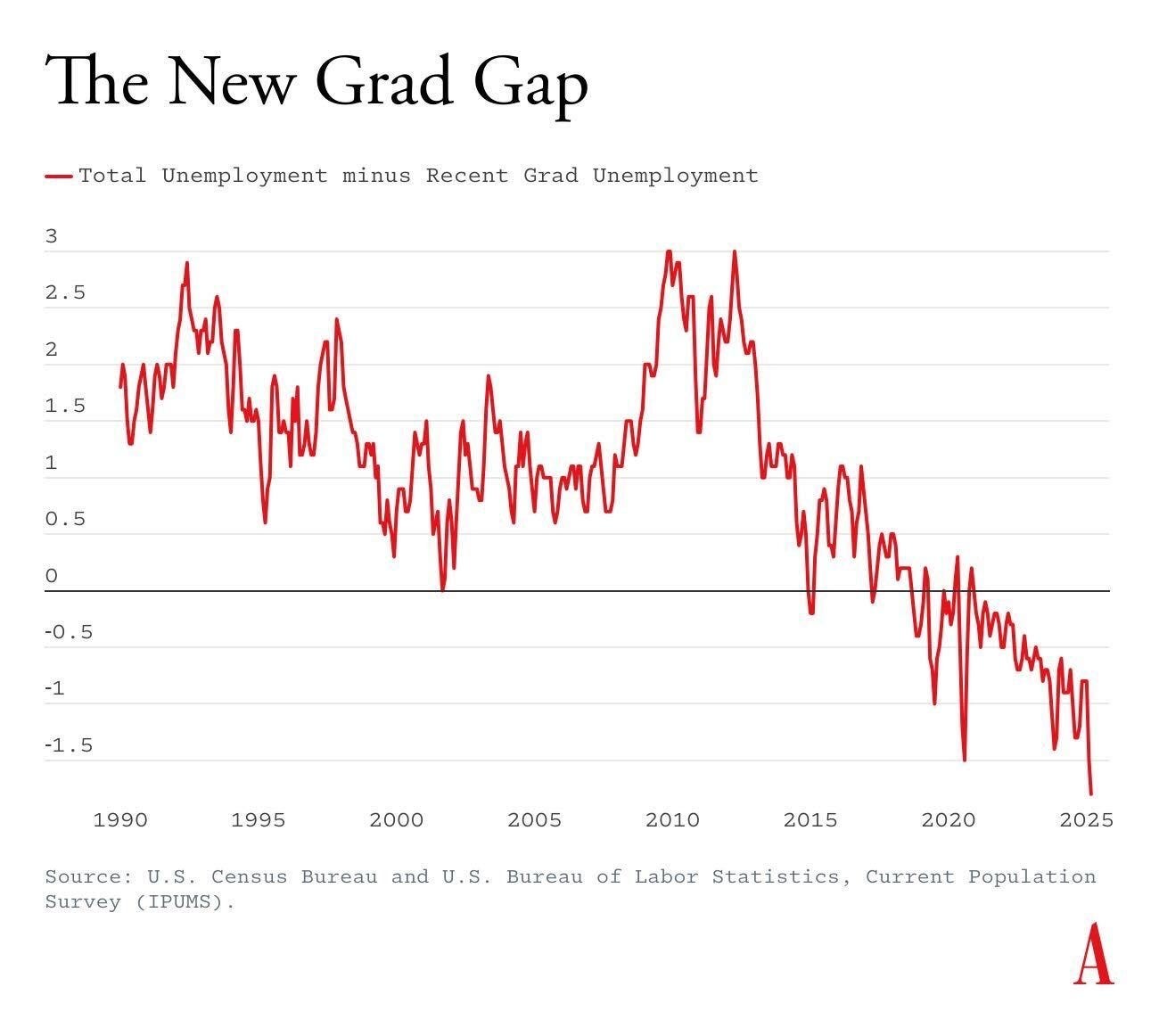

As such, employers hiring white collar workers (particularly tech workers) have to sort between 2x the number of new hires (adjusted for population change). As employers have never been particularly good at identifying talent, qualified applicants get left out or have to put in more effort to attain the same position. Empirically, the difference in unemployment rate between new graduates and the general population has been decreasing since the 10s, and new college graduates are now more likely to be unemployed than regular people:

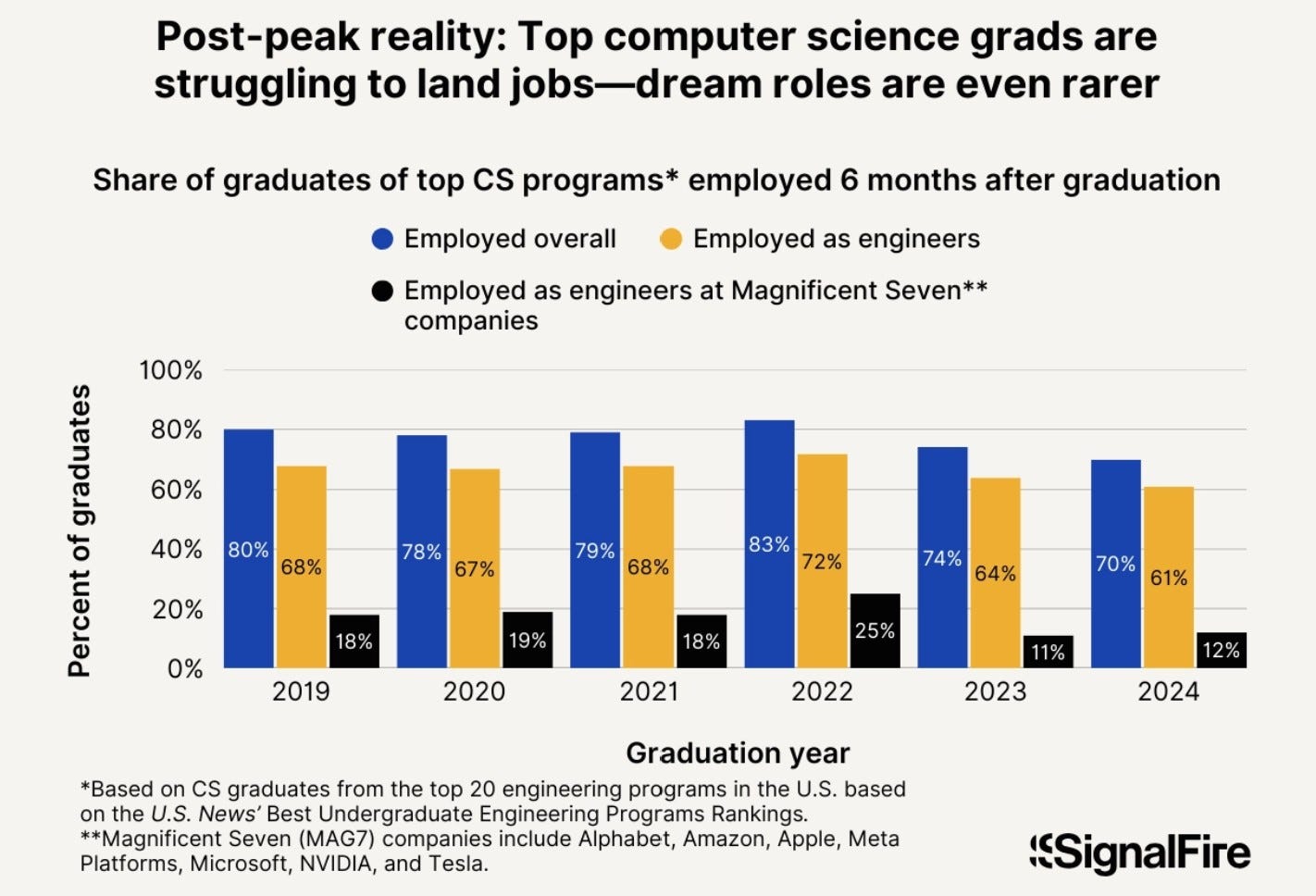

Even graduates of top CS programs are having trouble in the job market:

AI + the internet

The credential inflation problem has been going on a while, but the complaints with regard to the job market have been accelerating ever since 2022, particularly for tech jobs; AI is the obvious culprit here.

One would expect younger people to adopt new technology faster and therefore be better able to leverage it, but LLMs in particular have made it so employees in senior roles have started automating more of the menial work that they would delegate to interns or recent hires, therefore reducing their need for them.

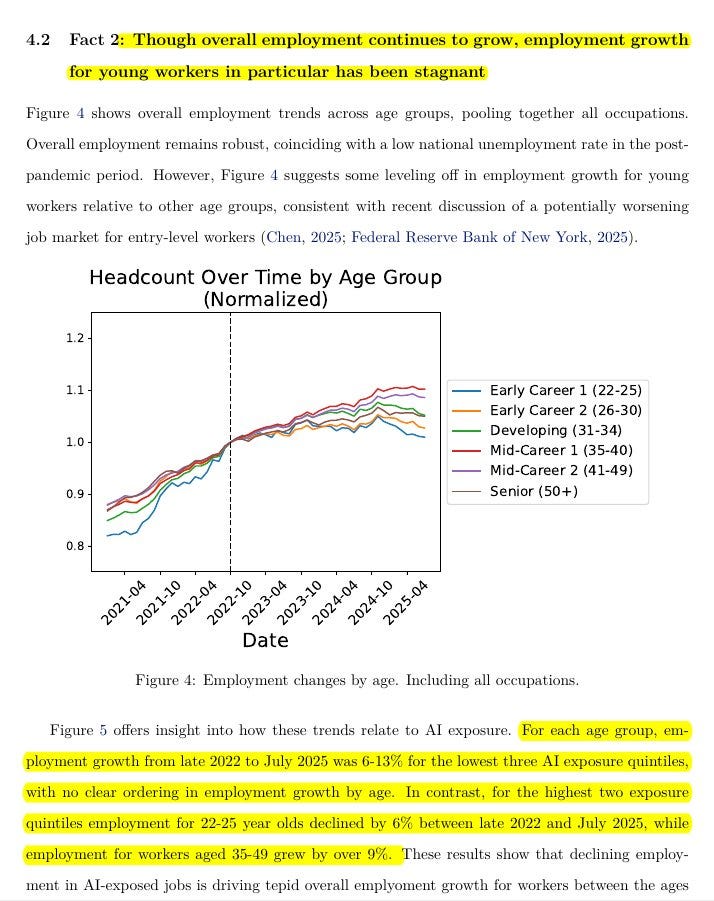

Empirically, the dropoff in hiring in certain occupation seems to have coincided with the adoption of LLMs:

This paper examines changes in the labor market for occupations exposed to generative artificial intelligence using high-frequency administrative data from the largest payroll software provider in the United States. We present six facts that characterize these shifts. We find that since the widespread adoption of generative AI, early-career workers (ages 22-25) in the most AI-exposed occupations have experienced a 13 percent relative decline in employment even after controlling for firm-level shocks. In contrast, employment for workers in less exposed fields and more experienced workers in the same occupations has remained stable or continued to grow. We also find that adjustments occur primarily through employment rather than compensation. Furthermore, employment declines are concentrated in occupations where AI is more likely to automate, rather than augment, human labor. Our results are robust to alternative explanations, such as excluding technology-related firms and excluding occupations amenable to remote work. These six facts provide early, large-scale evidence consistent with the hypothesis that the AI revolution is beginning to have a significant and disproportionate impact on entry-level workers in the American labor market.

The role of the internet in the job market is rather obvious. The internet allows people to send in massive numbers of job applications remotely. As the number of applications sent increases, the rejection rate increases, which is something nobody likes; sending job applications is boring for employees and employers get too many applicants to properly sort, so they must defer to ATS + AI + HR to sort out the mess.

Beyond the difficulty of getting a job, I suspect that a lot of malaise with regard to the job market is more related to the experience of mindlessly filling out form after form only to be rejected from 90+% of positions regardless of relevant qualifications or competence on the job because of the ATS/AI lottery.

I recently came through a stint of unemployment in the tech sector and think it would be helpful to share my experience. I'm in my 40s and have a long track record of success in my industry and my role, my specific skill set is hard to find, and there are lots of open positions being advertised for this role so I initially wasn't worried. The first few companies where I applied and thought I was an extremely good fit rejected me immediately without even a conversation. At first I was bemused: "If they don't want to even interview a candidate who is an exact match for what they are looking for, it's their loss", but as the rejections kept coming, even from a company where I knew the CEO personally and have spoken as a keynote speaker at their annual conference for 7 years in a row, I became very concerned. I talked to a hiring manager at a company I used to work for and he said that he gets 1000 applications a day for any open position and practically every single resume is a perfect match for the job qualifications meaning that who he chooses to interview is a lottery. But, he said, when he does actually interview the candidates, it's clear that many of them have vastly mischaracterized their skills and experience to match the job description with no regard to the truth. And of course because he's selecting those applicants who are perfectly matching, he's filtering out the more honest candidates who might have only 85% of the skills desired. Eventually, I did get a generous offer from one of the first companies that I actually landed an interview with, I suspect because once it was obvious that the skills and experience I claimed to have were genuine, but it did take two months and certainly wasn't pleasant.

Why is the cover picture of this a guy wearing a bowser backpack