Larger families have less successful children

but perhaps more cooperative ones

Bryan Caplan, in his book Selfish Reasons to Have More Children, argues that twin and adoption studies show that the shared environment is largely irrelevant when it comes to most traits that parents care about (e.g. personality, wealth, IQ, physique, appearance…), which suggests that parenting styles do not make a difference in a child’s life. As such, if one were to want a large family, they could do so without sacrificing too much of their time and attention.

My fundamental critique of Caplan’s argument is that “parenting” is encompassed by both the unshared and shared environment. If a parent helps one child but not the other, it is an unshared environmental effect, but if they help both children, it is a shared environmental effect in the twin model. The “shared environment” is also a variance component, not a measurement of effect; given that parents vary little in the amount of calories they feed their children, child malnutrition correlates poorly with future height and health, though this does not mean that a child who starves will not be harmed by the experience.

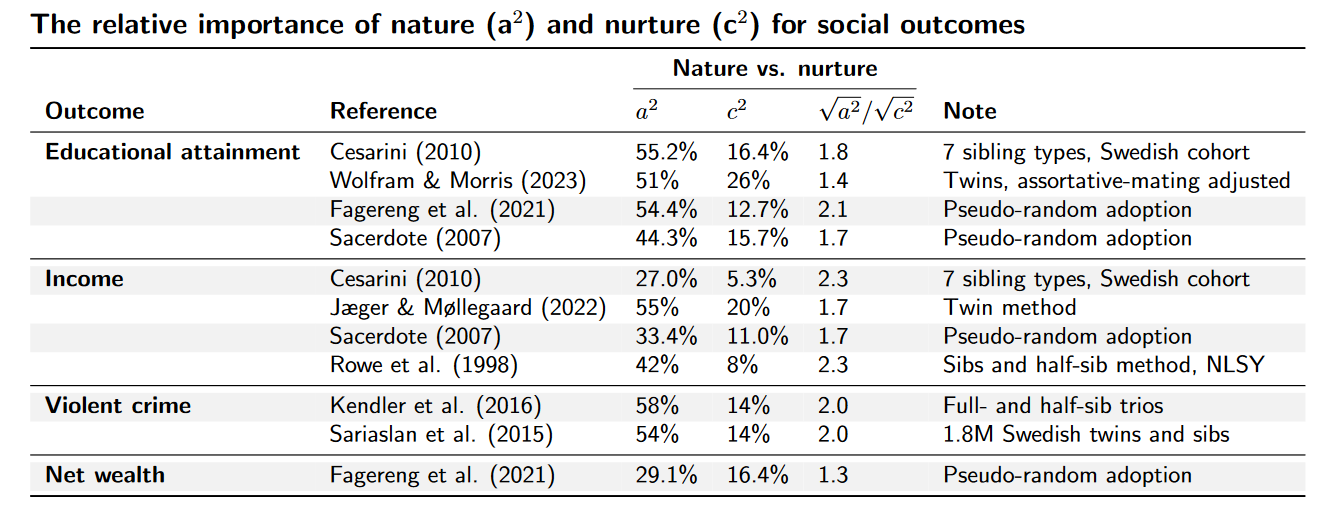

It’s also worth mentioning that the twin studies themselves, in the aggregate, typically show non-negligible effects of shared environment on socioeconomic status:

Korean children randomly assigned to American families show similarities to their American siblings, particularly in their drug habits and the prestige of the university they attend:

Birth order effects

Birth order studies have been criticized on multiple grounds: birth order effects could be an artefact of factors that vary between families, such as parental SES or family size. Some have come to suspect that birth order effects are an artefact of parental age, where younger siblings have older parents who have worst prenatal environments and mutations, and breed lower quality offspring as a result.

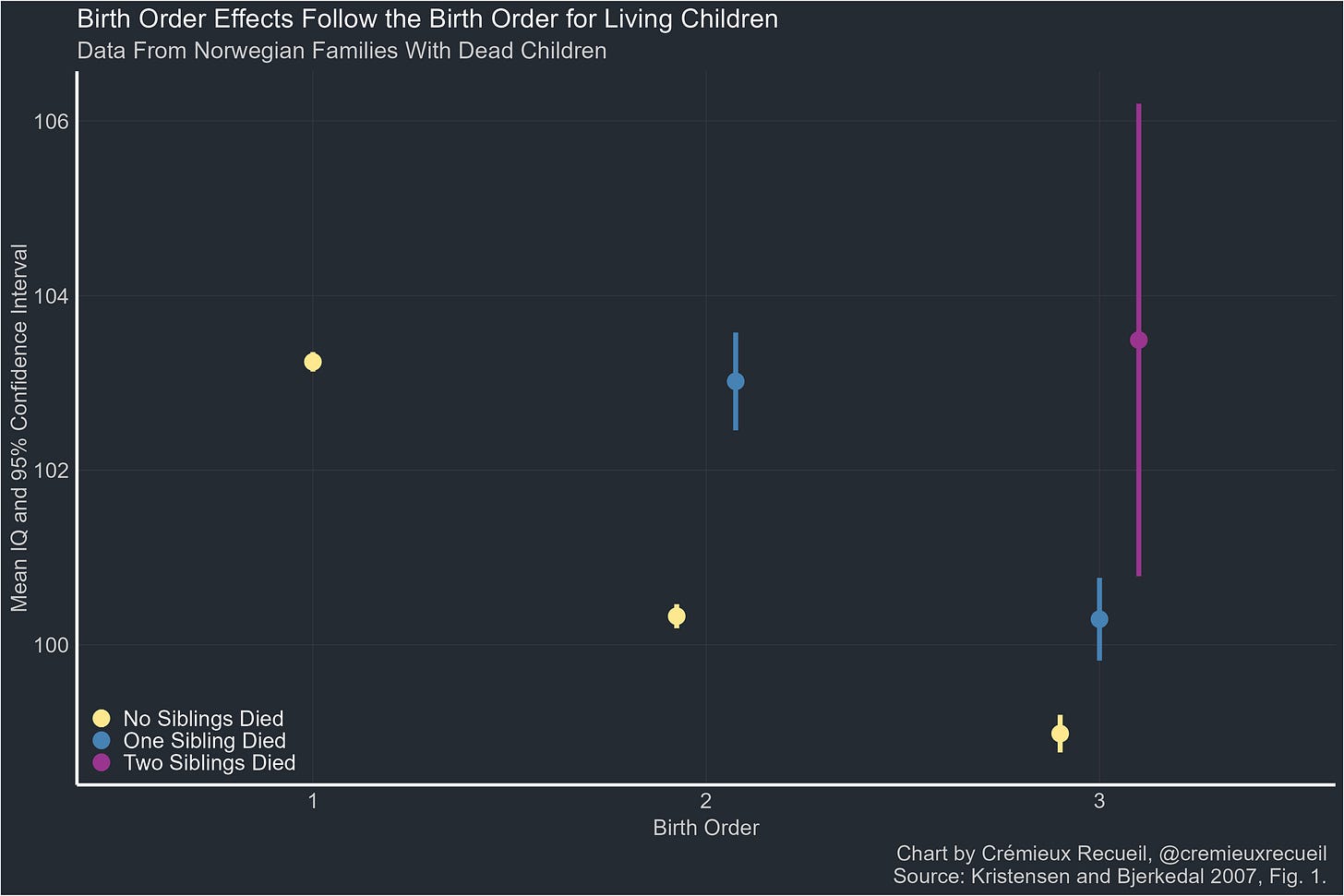

The family size confound problem is very easy to solve; use statistical models that separate the effect of birth order and family size1. The parental SES confound theory has been tested many times and I’ve never seen it confirmed. The idea that they are mutationally/hormonally caused is also wrong, as it is easy to verify that the effects are socially caused — just use deaths: if an older sibling dies in infancy, then the second-born will socially resemble a first-born. These tests find that, for intelligence, the rank order follows the social order:

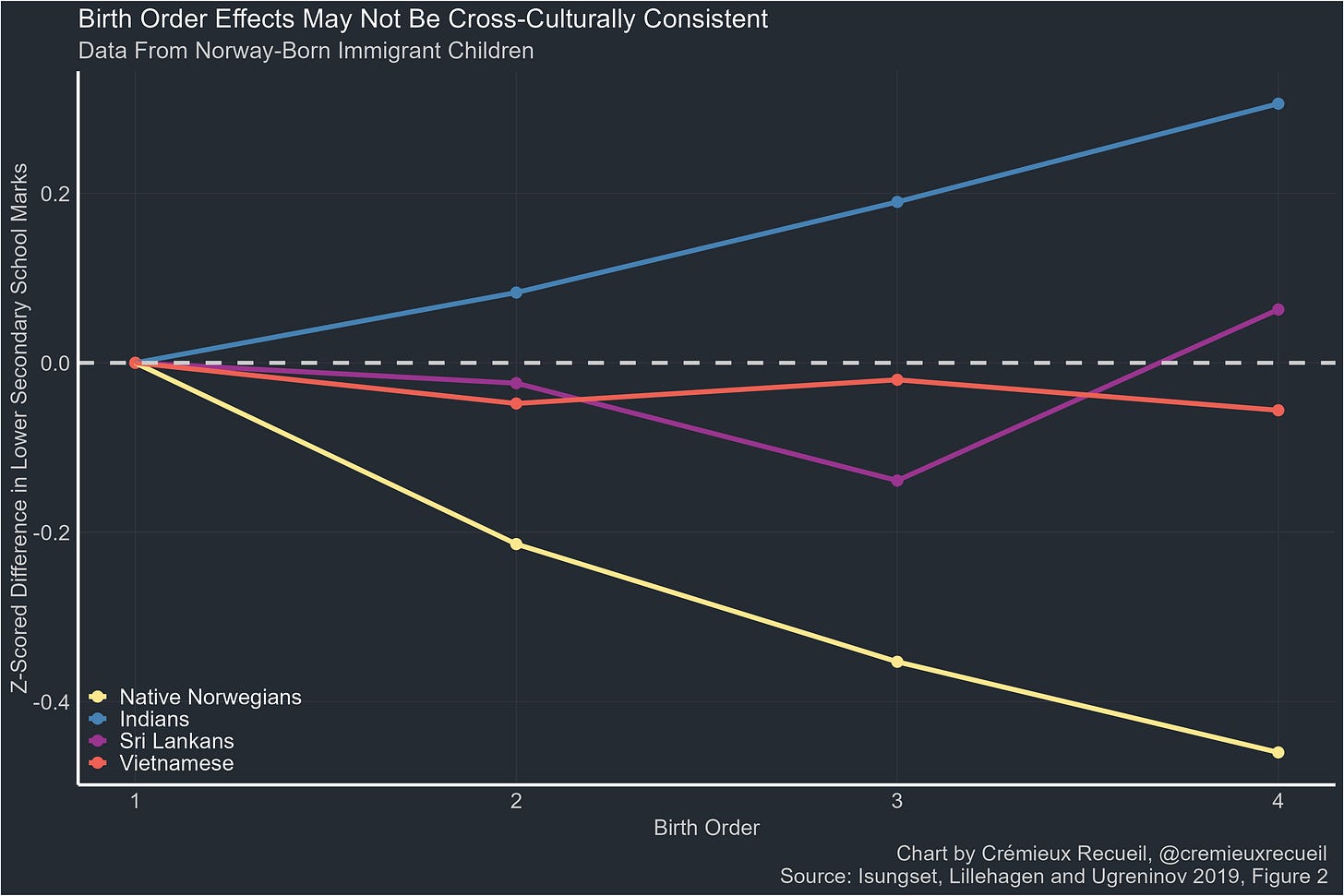

They also vary across cultures, implying that they are socially caused:

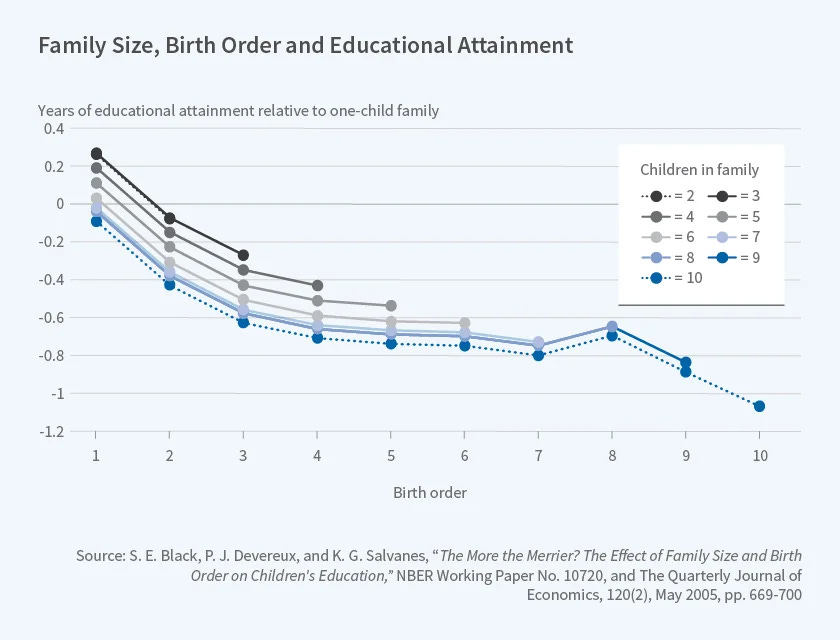

As of date, there is evidence for birth order effects in intelligence, education, income, height, BMI, and health; all of the effects survive controls for birth month/year and family size. Birth order effects on education are fairly substantial: a -0.2 SD penalty for each level in the order until level 5, controlling for family size. The birth order effect of intelligence (~2 IQ per level) explains about a third of this effect, as IQ/education correlate at 0.5 - 0.6, with most of the relationship going from the former to the latter. I assume the rest of the advantage is due to personality or rearing.

Birth order and personality.

Larger groups of people imply a weaker correlation between individual preferences and aggregate preferences. Members of said group will have to compromise on rules, activities, or resources. Therefore, one would think that living in a large family would make somebody better at working with others; in popular culture this idea is transmitted as “only child syndrome”.

I have found one study that does suggest that this is the case:

Ashton MC, Lee K. Personality differences between birth order categories and across sibship sizes. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2416709121

We examined associations of self-reports on the HEXACO Personality Inventory—Revised (HEXACO-PI-R) with birth order category and sibship size, controlling for participant sex and age. In a first sample ( N > 700,000 online adults, mainly from English-speaking countries), Honesty-Humility and Agreeableness both showed the highest means for middle-borns, followed in order by last-borns (youngests), firstborns (oldests), and only children, with differences between middles and onlys of d ≥ 0.20. The same result was replicated in a similar but smaller second sample ( N > 70,000) in which sibship size was also assessed, thereby allowing birth order differences to be separated from sibship size differences. In that sample, Honesty-Humility and Agreeableness showed higher means with larger sibship sizes, with differences between sibship sizes of 1 and 6+ of d = 0.30 and d = 0.36, respectively. Controls for upbringing religiousness and current religiousness reduced these differences by about 25%. Within sibship sizes, birth order differences in these dimensions were considerably smaller but oldests remained up to d = 0.10 lower than middles and youngests. Openness was d ≈ 0.10 higher for onlys than for non-onlys collectively, and within sibship sizes, Openness was d ≈ 0.10 higher for oldests than for middles and youngests.

In line with the stereotypes, middle children are the most agreeable, followed by last-borns, first-borns, and only-children. There are other studies that find no effect of birth order on personality, even with large datasets (total n > 20,000). Discrepant findings in birth order research are rather boring as there isn’t much to say beyond “this study found X” and “this study found Y”, but I am inclined to believe positive more than negative findings here.

I was also able to find one study that found that having a larger number of siblings lowers the odds of divorce — one sibling is associated with a reduction in divorce risk of 3%2, net of confounders such as their educational attainment, their parent’s education, whether their parents divorced, race, age, homeownership, region, year, gender attitudes, and religion.

If the divorce rate of an only child is 40%, then the predicted divorce rate of somebody with 5 siblings is 36%; I contend that this implies a moderate or large effect of family size on cooperation skills. Consider that the theory is that larger family size → cooperation skills → lower likelihood of divorce — there is a lot that goes into cooperation skills besides family size (e.g. genes), and there is a lot more that goes into divorce besides somebody’s cooperation skills (e.g. the other person in the relationship, circumstances, mutual respect). As such, one would not expect there to be a large effect of family size on divorce risk, even if the effect of family size on cooperation skills were to be considerable in size. It’s a multiplied effect size problem3.

I trust the 3% estimate p < .001 regression model over the 1.8% p < .05 model because it isn’t controlling for the Kitchen Sink.

if A causes B by .4 and B causes C by .4, then A causes C by .16.

People who have larger families literally are more successful children.

Ah, but do they have fewer successful children :)