Most people on the alternative right have come to accept that genetics account for a decent amount of the variance in behaviour and that this holdds for social classes and races as well. As discourse around this subject aged, people have now pivoted to discussing the implications of this information.

First, there is the issue of whether hereditarianism has policy implications at all, then whether it empirically affects people’s political positions, and finally whether it can function as a political platform. My conclusion is that hereditarianism indeed has massive policy implications, that it does have a moderate effect on people’s political beliefs, but that unfortunately it cannot be a political platform and will stay a fringe position in the near future.

I.

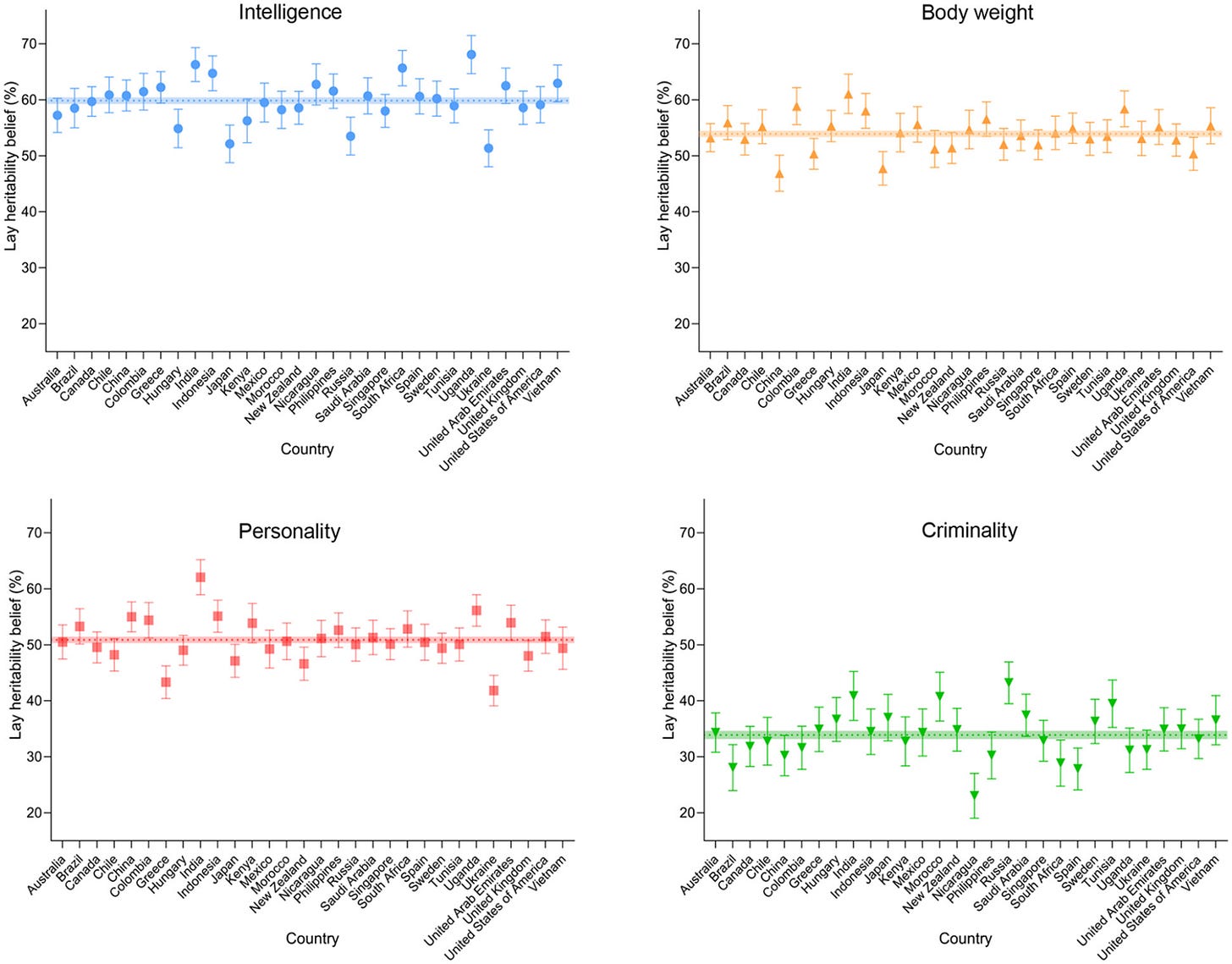

Hereditarianism at the individual level is taken for granted by most of the public: the median human believes that about 50-60% of the variance in intelligence, weight, and personality are caused by genes. I assume would assume these answers vary substantially by person: some people might think that intelligence is 100% innate, while others think that the heritability of intelligence is closer to 15%, like Sasha Gusev.

The estimates made are fairly accurate — for intelligence I’d peg the heritability at 60-90%, personality at 50-90%, criminality at 40-60%, and body weight at 50-80%. The estimated heritability depends a bit on the study and the method: variance in self-reported personality is less heritable (40-50%) than variance in clinical diagnosis or peer-ratings (70-96%). It’s difficult to judge which set of estimates to use — peer ratings or diagnosis might oversample the permanent variance in personality, while self-reports are, well, self-reports.

There is little polling on this, but I would assume that most people think that social interventions are effective, even though it is not what you would predict based on hereditarian theory. The stable component of personality and intelligence are far too heritable to be influenced by interventions. Less heritable traits like income, education, criminality, happiness, and whatnot, beyond being affected by talent, are also affected by a random component that is difficult to predict or measure.

This is not something that is agreed upon among academics — take for example this recent review article on sociogenomics:

Third, heritability is often erroneously interpreted as an index of policy relevance, with higher heritability leaving less room for environmental interventions to have an effect. But as noted by Goldberger (1979, p. 344): “The policy relevant effect of an explanatory variable is properly measured by its regression slope, not by its contribution to R2 ...” His memorable example is that eyeglasses can make a big difference even though naked eyesight is highly heritable. The facts that nutrition has led to large improvements in average height and that variation in height at any point in time is largely explained by genetic factors are not contradictory (Visscher, Hill and Wray, 2008). Moreover, policy can itself change heritability. For example, if income were redistributed from those with a high genetic factor for income to those with a low genetic factor, then the heritability of post-transfer income would be reduced. Rimfeld et al. (2018) find that after Estonia gained independence from the Soviet Union, the heritability of educational attainment and occupational status increased, and they interpret this change as resulting from an increase in meritocracy.

The argument is that the efficacy of interventions is analogous to the magnitude of the regression slope of environmental effects on traits, not the percentage of observed variance that is caused by the environment.

This is fallacious reasoning. There are exceptions to the rule such as eyesight and body weight where a heritability coexists with malleability. But a high heritability implies that, on average, effective interventions are much less likely to be discovered.

Allow me to be more concrete. Heritabilities are affected by the following four factors:

The effect of genes on a trait.

Genetic variance within the population.

The effect of the environment on a trait.

Environmental variance within the population.

The factor that is most relevant in relation to the efficacy of interventions is clearly the third. But the other three matter as well: the larger the first two factors are, the lower the relative impact of an intervention will be. And the lower the environmental variance, the more difficult it is to judge which environmental factors are causal for trait variance. Because of this, heritability and the efficacy of interventions should be expected to strongly correlate.

This is supported by the literature on interventions fairly well, at least the ones that correct for publication bias and other common biases. Allow me to elaborate:

Educational interventions do not increase academic ability.

The effects of IQ interventions fade out after a few years.

Mindfulness interventions are not effective.

Many medical and dietary interventions are probably not effective.

The efficacy of psychotherapy is overstated by publication bias and regression to the mean.

Interventions to reduce criminal reoffending are probably not effective. And Norwegian recidivism is not uniquely low, contra reports from the media.

The cross-sectional relationships between income and crime are not causal, based on studies that use lottery winners to estimate the causal effect.

Relevant to the discourse on interventions is what I like to call the “shared familial confounders” literature, which analyzes whether associations between family background and behaviour survive controls for genetic and cultural confounding.

Take, for example, a study that tracks family income longitudinally and tests whether differences in income within a family predict differences in the criminal offending of children.

We calculated mean disposable family income (net sum of wage earnings, welfare and retirement benefits, etc.) of both biological parents for each offspring and year between 1990 and 2008. Income measures were inflation-adjusted to 1990 values according to the consumer price index provided by Statistics Sweden (http:// www.scb.se/en_/). Econometric researchers have long recognised that single annual income exposure measures generally suffer from substantial measurement error because of their inability to accurately depict long-term SES, often leading to attenuation bias.18,19 Therefore, annual variables were used to calculate the mean parental income throughout each offspring’s childhood (ages 1 through 15).

[…]

To assess the effects also of unobserved genetic and environmental factors, we fitted stratified Cox regression models to cousin (n = 262 267) and sibling (n = 216 424) samples with extended or nuclear family as stratum, respectively. The stratified models allow for the estimation of heterogeneous baseline hazard rates across families and thus capture unobserved familial factors.23 This also implies that exposure comparisons are made within families.24 Model III was fitted to the cousin sample and adjusted for observed confounders and unobserved within extended-family factors. Model IV was fitted on the sibling sample and accounted for unobserved nuclear family factors and for gender, birth year and birth order

They do not.

This is also the case for criminality in the United States, according to the Bell Curve:

We will use both self-reports and whether the interviewee was incarcerated at the time of the interview as measures of criminal behavior. The self-reports are from the NLSY men in 1980, when they were still in their teens or just out of them. It combines reports of misdemeanors, drug offenses, property offenses, and violent offenses. Our definition of criminality here is that the man's description of his own behavior put him in the top decile of frequency of self-reported criminal activity.''0' The other measure is whether the man was ever interviewed while being confined in a correctional facility between 1979 and 1990. When we run our standard analysis for these two different measures, we get the results in the next figure.

Both measures of criminality have weaknesses but different weaknesses. One relies on self-reports but has the virtue of including uncaught criminality; the other relies on the workings of the criminal justice system but has the virtue of identifying people who almost certainly have committed serious offenses. For both measures, after controlling for IQ, the men's socioeconotnic background had little or nothing to do with crime. In the case of the self-report data, higher socioeconomic status was associated with higher reported crime after controlling for 1Q. In the case of incarceration, the role of socioeconomic background was close to nil after controlling for IQ, and statistically insignificant. By either measure of crime, a low 1Q was a significant risk factor.

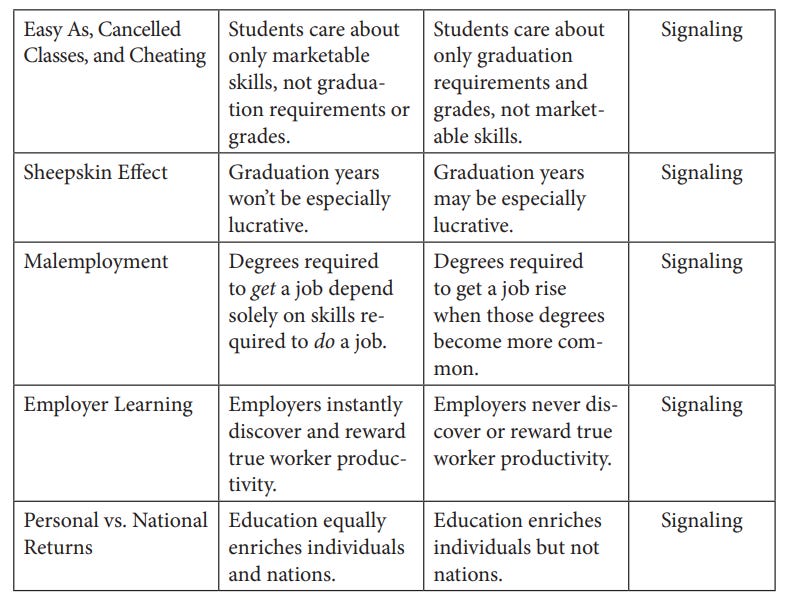

Hereditarianism also predicts that returns to education are largely due to signalling instead of improvements to ability — this appears to be the case, according to Caplan’s The Case Against Education. Properly making the case for this in an unrelated article is impossible, so I will simply post his summary:

There are a few social interventions that seem promising: divorce cooling off laws, intense tutoring, and nudging. Besides that, the rule is no efficacy.

III.

Back to the topic of hereditarianism and politics.

Let me be clear: it would be delusional to think that what I described earlier does not have massive policy implications. Based on the lottery and family confounding studies, redistribution is likely to have no effect on criminality and mental well-being. Increasing the educational attainment of children will increase their earnings, but this is largely because degrees signal ability, not because the education system is improving their abilities.

Some simple policy proposals based on these claims:

No economic redistribution. Income has a small or null effect on mental well-being, does not affect the criminality of children, and income inequality is not associated with social ill between countries

Set funding for social interventions to zero.

Make graduating from high schools and universities much more difficult, and make SAT/ACT scores public.

While hereditarianism may theoretically have massive political implications, that doesn’t mean that the public will agree.

Within experts in intelligence research, right-leaning attitudes correlate at .48 with the percentage of variance in the Black-White IQ gap they think is caused by genetic factors.

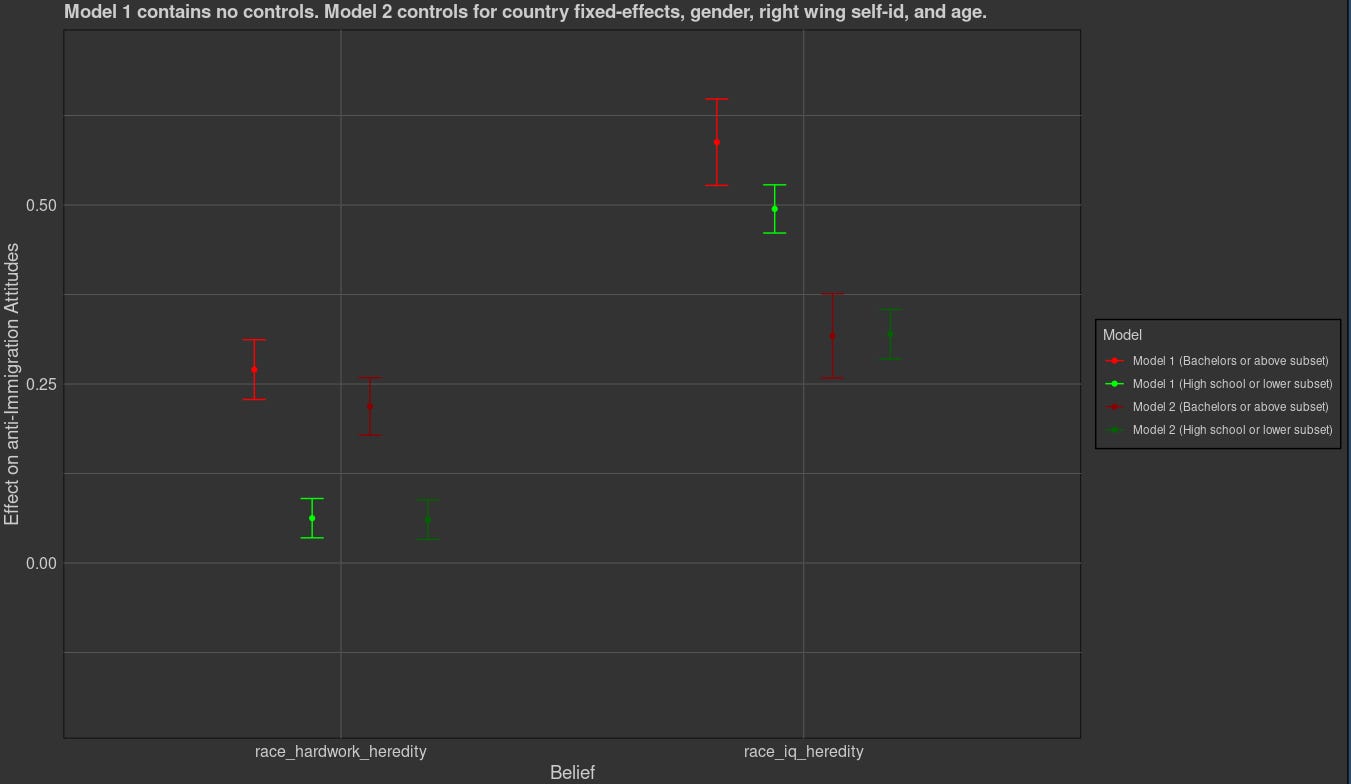

A big effect, but the study has clear limitations (non-representative sample, opaque causality), so I analyzed the ESS dataset to test whether race realism affects political policy beliefs. The survey asked about whether races differ in inborn intelligence and ability to work hard, as well as some questions about immigration that I aggregated into one composite score to better measure their opinions.

Here are the descriptive statistics of the variables and the correlation matrix.

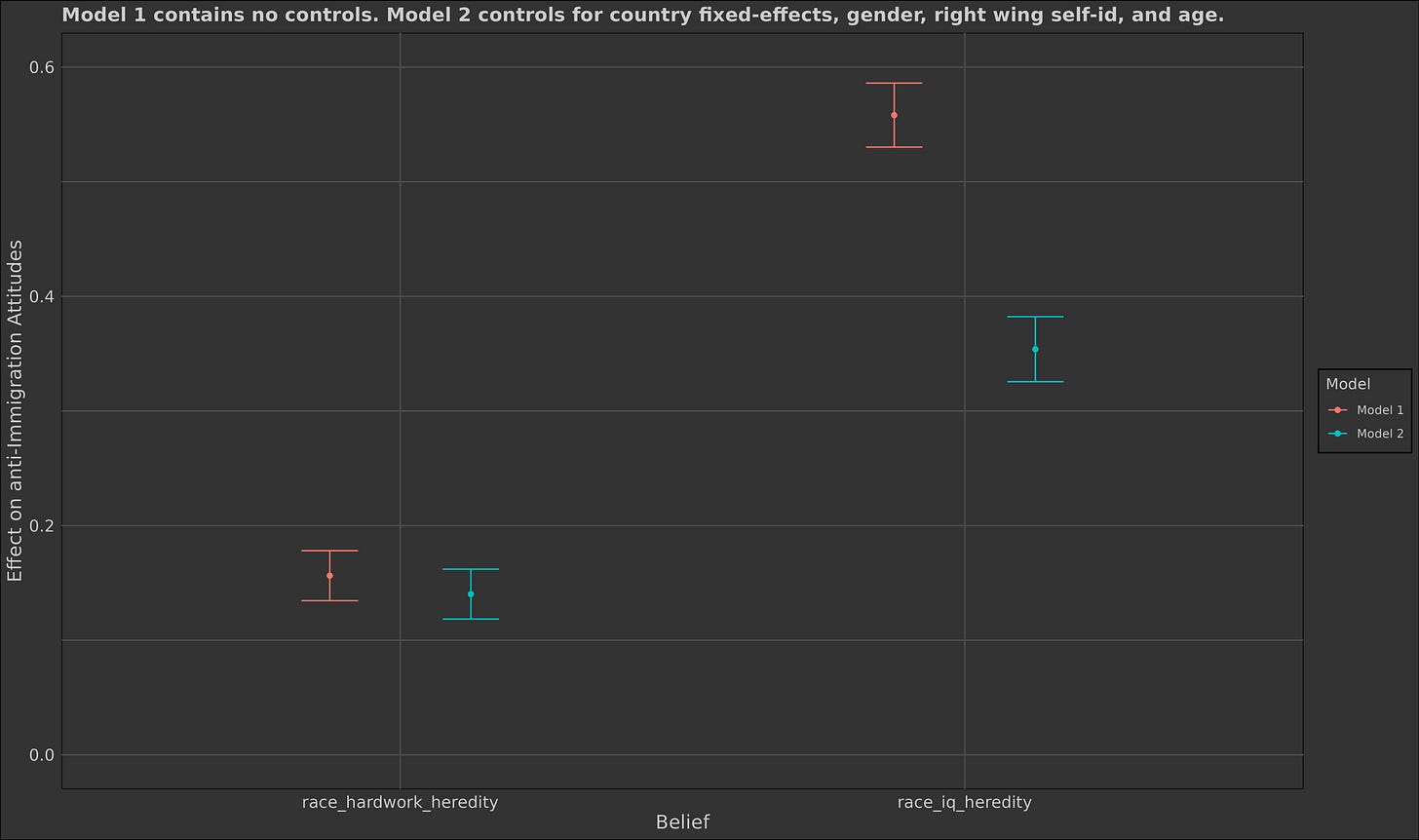

I tested the effect of believing in both strands of hereditarianism on support for restricting immigration using two models:

Model 1: anti_immigration_attitudes ~ race_iq_heredity + race_hardwork_heredity (no controls)

Model 2: anti_immigration_attitudes ~ race_iq_heredity + race_hardwork_heredity + cntry + rcs(age, 6) + righwing_stand + gender (controls for age, gender, and country fixed effects)

These are the results:

After implementing the proper controls, believing races differ in innate intelligence appears to have a moderate effect on being against immigration (0.4 SD), while believing races differ in innate conscientiousness has a smaller effect on being against immigration (0.15 SD). None of these effects seem very encouraging to me.

I also tested another theory: whether this effect depended on political interest. I subsetted the data to two subsets: those who said they were ‘very politically interested’ or ‘not at all politically interested’. The effect of believing in IQ-based race realism did not differ between groups, but the effect of conscientiousness-based race realism increased by a large amount within the politically interested subset.

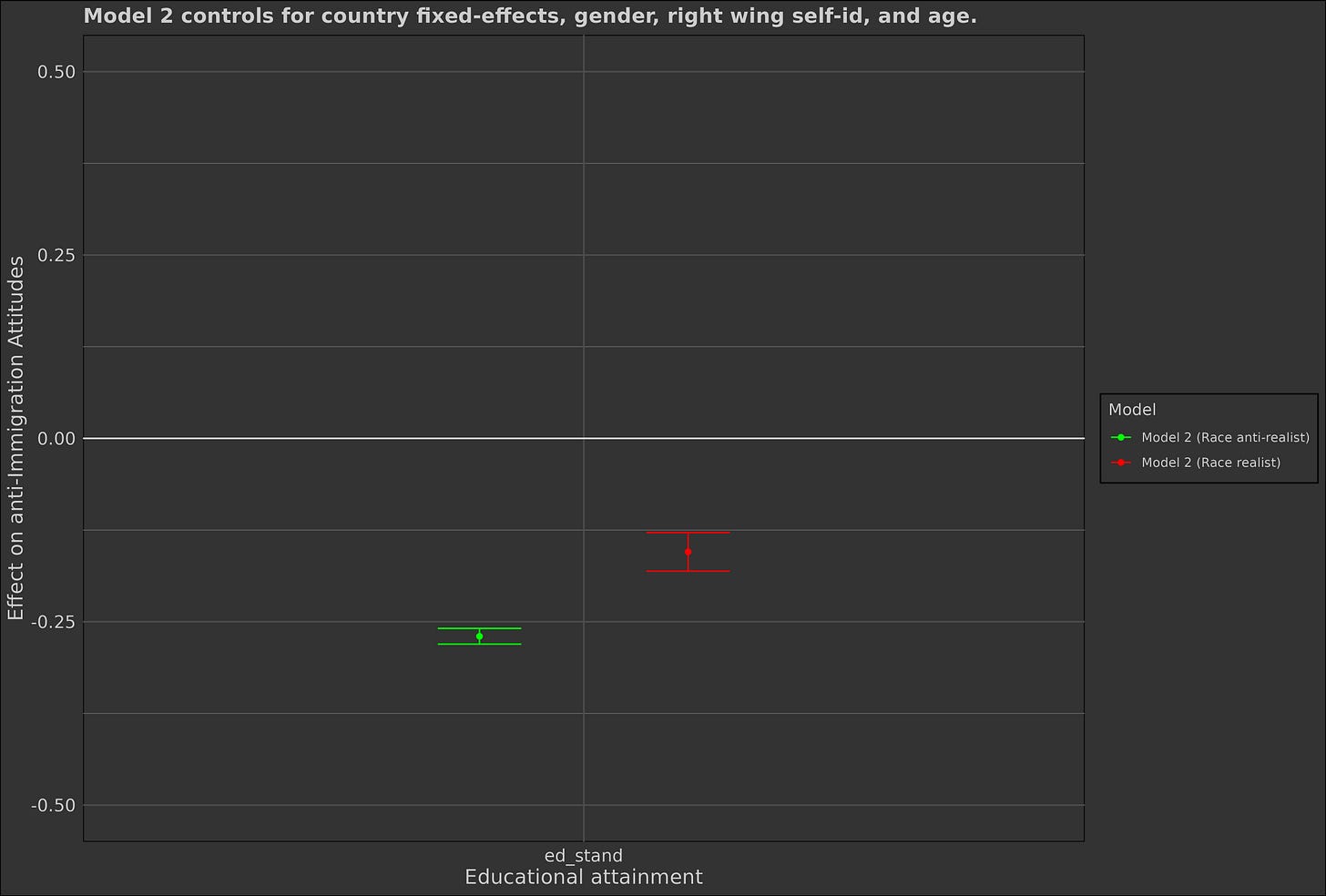

I also tried testing what I like to call the ‘Cofnas theory’, which is that wokes are more intelligent than non-wokes because the equality thesis implies wokeism is true. I tested for this by observing whether there was an interaction between educational attainment (proxy for intelligence) and hereditary belief when predicting attitudes about immigration, and it did exist. But this could also be due to highly educated people having more consistent responding patters; I would not put too much stock into the results.

IV.

Hereditarianism as a theory has massive political implications. And some people in the public seem to agree, at least those who are politically aware and smart. But this is not a project that can be communicated at a large scale because of game theory, as Spandrell notes in his article on the hereditarianism of politics.

If groups and individuals differ in valuable traits, then there must be differences in value between groups and individuals. This is the case regardless of whether the differences are genetic or environmental, but more so if they are genetic, as the sexual marketplace is the pinnacle of all other markets, and bad genes imply lower sexual value.

Hereditarianism also implies that “unfair” causes of status (e.g. family background, luck) are less relevant than the ones that cannot really be attacked on moral grounds (genes). Because of this, people who favour redistribution and rent-seeking will try to deny heredity, while those who do not favour these policies will argue that the differences between the successful and the unsuccessful are genetic.

The successful and the well-bred have little to gain from cooperating to promote heredity as a political program, while the rest of the populace have much more to gain from promoting redistribution and rent-seeking operations. Advocates for the inefficacy of social interventions will not be perceived as the better angels of our nature, but as political actors who are promoting the interests of a certain group over another.

Besides the game theory involved, the deterministic implications of hereditarianism are uncomfortable. Behavioural genetics models tend to assume the existence of several factors, such as an additive genetic factor, an unshared environment, a shared environment, a vertical transmission effect, and so on. In no paper have I ever seen a “free will” variance component, simply because choice independent of genetics and environment is impossible.

A detail I’ve seen overlooked is that the percentage of intelligence researchers who believe that genes account for a substantial fraction of the difference in ability between Whites and Blacks increased from 1970 to 2020. This is not a surprise to anybody who has been following the field, which has experienced a slow burn of published findings being more consistent with the hereditarian theory (e.g. transracial adoption studies, GWAS hits, persistence of the differences).

There is not one single paper that proved it: a cultural model fits the transracial adoption studies, the admixture results could be explained by environmental confounding, and the polygenic score hits could be a coincidence. But it is a bit convenient that every observation that would be expected under the hereditarian theory just happened to be true.

This release of information and change in expert consensus coexisted with a worsening of the political situation and the decrease in the number of people who support hereditarianism. Because of that, it is unlikely that expert consensus within a field can independently have a large effect on politics: many more factors like the media and the rest of academia have a role to play in what happened.

Another thing that has gone under the radar is two recent papers published by “normal” people who argued that group differences in traits such as education and cognitive ability are caused by genes. The former argued that this was the case for differences between White people in the United Kingdom, while the latter argued that some alleles that are associated with cognitive ability are not expressed to the same extent within Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics.

Not trying to paint any targets here, but from what I see, there was no outburst over any of these papers, and the first authors of both papers are still employed at their respective universities. So it’s not implausible that, in the future, researchers could publish pro-hereditarian pieces, as long as they are not written by “bad” people and do not cite “bad” people.

Could this shift public consciousness? I’m going to take the contrarian position and say no. The arguments that involve molecular genetic evidence have already been abstracted to oblivion, as polygenic scores are not comparable between races due to LD-decay bias and several other factors. There are ways these biases can be adjusted for (according to colleagues), but making these corrections does not stop the argument from being abstracted, therefore less accessible, and therefore less influential. I also note that NONE of these pieces got any media attention, as was the case for the Reich and Alex Young admixture papers.

The races, classes, and sexes will remain unequal for as long as the genes stay the same. We have been trying to eliminate these inequalities for about a hundred years now; at some point, people will start asking questions about what exactly is causing these differences. Or, maybe society could collapse and the forces that were causing people to look the other way vanish.

Because of this, I do not believe that the current political climate can remain for eternity. At some point, the cost of denying a reality that is becoming increasingly obvious will outweigh the rhetorical benefits of doing so. When this happens, I predict the left will move to the Harden liberalism position, which is that HBD is true, but all of the left’s policy choices should be pursued anyway.

Appendix

Variables used from the ESS.

Interaction test. Note that more ‘polintr’ = less interest.

Testing the Cofnas theory.

Reliability of composite of immigration attitudes.

Figures that are too complicated to read:

´´Hereditarianism also implies that “unfair” causes of status (e.g. family background, luck) are less relevant than the ones that cannot really be attacked on moral grounds (genes). Because of this, people who favour redistribution and rent-seeking will try to deny heredity, while those who do not favour these policies will argue that the differences between the successful and the unsuccessful are genetic.´´

This is wrong. First of all, one can absolutely attack genes as unfair and this is already done. For example, liberal and socialist philosophers, when arguing why income inequality is unfair, will argue that the effect of genes in creating differences in people's abilities, is one reason why income inequality arising from differences in abilities is unfair. Just as an individual cannot choose the parents who raise him, he also cannot choose his genes, this is the most obvious argument in the world.

You just don't see this argument in the mainstream these days, because hereditarianism has become such a taboo, but the creators of the Welfare State were often hereditarians who explicitly argued that redistribution to the poor was moral because the poor could not be morally culpable for having the genes that they have, it would then be immoral to let the poor suffer from material deprivation. If hereditarianism were to become dominant again, leftists would just have to return to those arguments.

One policy that hereditarianism would make very difficult to defend is low-skilled immigration, because nowadays the justification for low-skilled immigration is often that the children and grandchildren of these immigrants will integrate and become like natives. Of course, this wouldn't be an argument against high-skilled immigration, and one always has the option of just being a pro-open border utilitarian like Bryan Caplan.

It is difficult to see how conspiracy theories about White privilege could survive hereditarianism, because these conspiracies are dependent on a factual version of the world where hereditarianism does not exist, where every group has exactly the same abilities on average, and where therefore group inequalities are attributable to evil actions on the part of White people.

> choice independent of genetics and environment is impossible. Philosophers settled this issue years ago.

It’s not true this is a settled issue in philosophy. Why do you think (libertarian) free will is impossible?