Zoomers are characterised by being the first to grow up with the mass internet. Did it make them lazy? Tiktok-brained? Dumb? Anxious? Autistic? Pathetic? People post charts and stories that support each of these narratives, but the internet’s weak memory and attention span seem to impede progression towards understanding and agreeing on what has happened to the zoomer.

The biggest trend I see in zoomers anecdotally is that they are more concerned with status than previous generations, even controlling for age. I have no empirical evidence for this being the case, but I do see it anecdotally, especially in the tech world. Most of the gen x or even millennial tech people like Musk or Zuckerberg were just nerds who did stuff and made money, while the younger founders of today like the Cluely guy are usually motivated by attention or status.

In the early phases of the mass post-2012 internet, content creators asking for money was seen as gauche and grifty. Now, that’s totally normal. I think a similar thing is happening with status, where it used to be gauche or weird to talk about status openly, but now people don’t seem to mind as much — “codes as low status”, “countersignal”, “elite”, and “high-agency” weren’t in tech people’s vocabularies 20 years ago.

I don’t think a lot of the data people cite to argue for this being true is valid — some have cited a gallup poll that finds that Americans have begun to value money more, though that could simply reflect a more pragmatic or utilitarian mindset. Some articles talk about how zoomers are starting to see jobs like “influencer” as increasingly attractive, but that could also reflect changes in what is perceived as high status.

The clout focus in zoomers is not some weird neurosis or fad, instead it reflects rational behaviour and responses to incentives. The macrocause is the internet1: an environment with a low barrier to entry that everybody can participate in regardless of their location/race/class. It fosters a competitive environment where the winners take over and the middle is hollowed out.

The internet makes status fungible, easy to verify, and internationally visible. If you are high status in X community, then that also translates to status in Y community, just to a lesser degree. People are impressed by credentials or titles from institutions that they do not belong to or have never even heard of. Partly because people understand that subcultures assign value to similar kinds of people, but also because we are all just apes that see imaginary numbers over people’s heads.

The internet also makes it so clout isn’t an end, but a means for connections, sponsors, relationships, friendships, and information. To some extent this has always been true, but the internet as an envornment has magnified the effect. People who aren’t temperamentally predisposed towards chasing clout might try to do it anyway because they care about the things status can give them.

My interpretation of zoomer behaviour being driven by incentives is not a tacit endorsement; this is one of the worst developments to come from the internet. Chasing status for the sake of itself is slavish. Even if the people who want status chase it for their own ends, they are still placing the group’s value function over their own. The path of the noble man is to do the thing in itself, for the thing in itself.

The debate on chasing passion vs chasing clout/money/realism is complicated, but this is my view on it: people who are really good at things do them because they like them. Or more accurately, because they receive rewards from doing them, which might come in the form of social status, but frequently does not. I’ve heard it’s common for professional athletes to not be passionate about the sport they play, but I doubt that applies to, say, scientists. I attribute this to extra motivation: the passionate noble is motivated by the thing in itself + money + status, while the striver is only motivated by money and status.

I don’t really believe in authenticity, so I don’t criticise this trend on the grounds that it surpresses our “true selves”, but I do believe in relativity. I don’t think everyone should have the same values or goals, and that they have to create2 them.

Often, when one starts doing a craft, they aren’t good enough to make it on the grounds of their own ability because they are, well, new to it. Chasing passion makes going through the initial phase of getting good at something much easier, since rewards will come from doing the thing in itself. The slave feels no such satisfaction.

Attention span

The main focus of this post is about the status-seeking trend in zoomers, though I figured that I would speak on the other trends that differentiate zoomers from the previous cohorts.

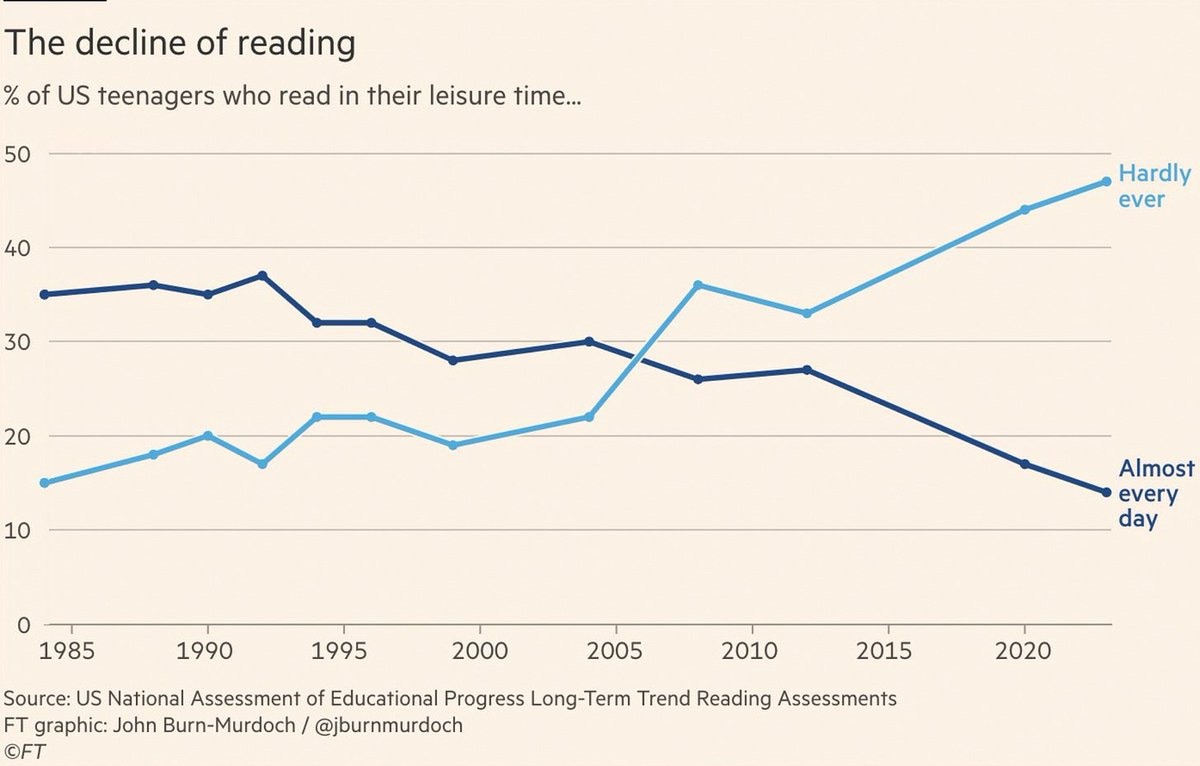

Shortening in attention span in the youth is something I and many others have noticed that can also be empirically proved. The best quantitative evidence of this is that zoomers simply read less than their elders now:

One could argue that perhaps this trend is specific to reading, but if one looks at internet platforms and their users, the same pattern emerges: Gen Z dominates shortform platforms like snapchat, tiktok, and instagram, while media like TV, facebook, and youtube have relatively older userbases.

The attention and status trends are also connected. Status is something that can be communicated easily and quickly, while other characteristics like value, truth, or motivation are harder to parse and require more time to judge.

A more uncommon rebuttal to this narrative is that there is a Flynn Effect in terms of concentration and sustained attention, with recent cohorts seem to be outscoring higher cohorts. This is only a good criticism if one thinks the problem is that zoomers don’t have the intellectual ability to concentrate, the issue could simply be the informational environment and the habits it creates.

I think this is bad. Genuine understanding of anything, be it a trade, skill, or field, must be acquired through longer content and sustained attention. Tiktok might not actually make people dumber, but it will not teach people anything more simple than an internet meme.

Risk assessment

There is no good psychometric evidence for risk assessment having changed in zoomers, but there is a lot of good behavioural evidence. Drinking, smoking, getting pregnant as a teenager, and approaching the opposite sex are all dropping among the recent generation.

What I don’t understand is how exactly risk assessment changed: have zoomers gotten more calculated in terms of their risk assessment or more conservative? The difference here being that conservatives do not want to take risks regardless of how good they are, while calculated people simply take better ones.

One could argue that not wanting to approach the opposite sex is a clear marker of conservatism — the worse thing they can say is no. Which is well, not actually true. While it is correct that the social and legal risks of approaching the opposite sex (particularly women) are overblown, approaching the opposite sex carries an energetic and emotional cost that people don’t want to admit exists.

It’s also further confounded by the problem of arrested development: teenagers are working and driving less as well, activities which aren’t really that risky, but require a certain level of advancement and desire which just isn’t there. Given the decline in traditional risk-taking behaviour extends to drug use as well, I’m inclined to think that risk assessment is genuinely changing beyond just the effects of slower maturation.

Acceptance of foreign cultures

Millennials weren’t a particularly racist or xenophobic generation, but the white ones did keep outside culture like anime at a distance. People into anime or games kept those interests to themselves or had to stand up to bullies. Some time around 2010-2015, everything changed and watching anime and listening to KPOP became as normal as watching TV. This is also reflected in zoomers adopting black and nazi/incel slang.

This mainstreaming of foreign cultures is good in my opinion. It’s worse a symptom of the greater problem which is that culture and art have begun to stagnate everywhere, be it TV series, games, anime, or film3. This can be inferred from the rise in sequels and remakes in the past 20 years and from, well, observation with the naked eye. Anybody who wants to experience art or media that is actually good will be forced to branch out.

The myths

Some have speculated that zoomers have become depressed, autistic, dumb, or lazy. The source of blame for these illusory changes in highly generic traits is always “da fonez”, no matter how much genetically-informed studies suggest social media does not cause mental health issues. Others have written good debunkings of these myths, so I may as well link to them explanations:

Autism: diagnosis of autism has increased over time, but symptoms for it have not.

Depression: depression rates have increased in the United States, but this is not true for the rest of the world. There is also no guarantee that this isn’t one of those cases of traits changing over time due to diagnostic drift or some other artefact.

Test scores: changes in test scores over time rarely pass measurement invariance.

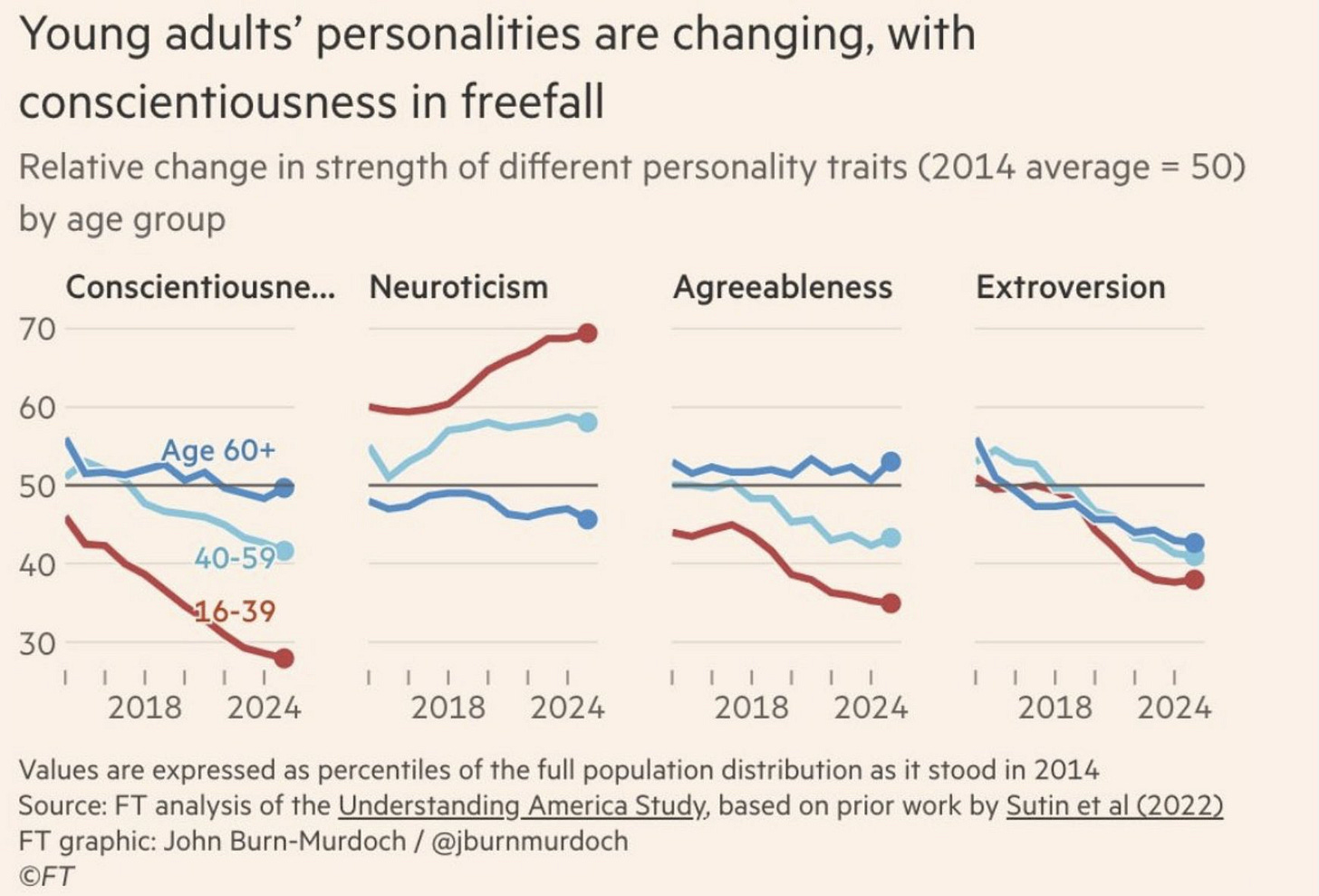

Laziness: the original FT chart was misleading, and the change in conscientiousness it portrayed was a simple d = .40 effect (analogous to 6 IQ points). It’s also not clear if the effect would survive controls for measurement invariance; zoomers are more likely to stay inside or engage in brainrot hobbies, but that could reflect cultural/environmental changes rather than psychometric ones.

The Verdict

Zoomers are looking like a rough generation. I might be more optimistic about us than some, but the clout-chasing fad and short attention spans are going to do in a lot of otherwise talented people. I once thought that zoomer artists would clear out the Millennials in terms of quality, as they weren’t infected with the same authenticity/irony culture, but now I’m not so sure. Making good art requires having a long attention span and an appreciation for the thing-in-itself, things I do not see as often in my generation.

The computer models predict that the fraction of >130 IQ people peaked somewhere between 1990 and 2020, given that most big creative/intellectual work is accomplished by people between the ages of 20-40, an IQ-only model would predict that the most artistically eminent generation of people were the Xers and early Millennials. I do think intelligence and creative ability are correlated, though not to the point that one can deterministically predict artistic achievement across time with this model.

See Mikka’s take on The Average is Over:

When I was a teenager I read Tyler Cowen’s book Average is Over. It posited that two things are, basically, unique to the 21st century.

Globalised economies of scale

The Internet

The combination of these two things means that for any job, there is someone, somewhere in the world who can do that job better than you; and that this person can monetise doing that job to a global audience. The rewards are much higher but the opportunity for success is much lower as well. Cowen, iirc, uses the example of a violin player; if the best violin player in the world can upload their recordings to YouTube, they can get a potentially greater audience than any classical performer ever did in the 19th or 20th centuries, it also means that many will be less incentivised to patronise their local concert hall when they can listen to much better music at home.

Yes, create. Nietzsche wasn’t wrong about that one. “You” (the conscious you, the fake you) don’t create your values, but YOU (your body, the real you) does.

Music I think is the one exception to this. Radio music is stagnating but there’s still a lot of good and even popular songs that are better than what came before. Youtube/soundcloud + cheap DWS tech is a boon to the industry.

> people who are really good at things do them because they like them

This, I think, is wrong. A myth at best, flat out untrue empirically, and very misleading at worst.

What you need is a positive feedback loop. The nature of that feedback look probably DOES play a role in the rate of success as well as the qualities of the resulting outcome. But the positive feedback loop is the driver, and while it can be borne of liking what you do (which again must split into very different kinds of scenarios!), it can also be slavish, devoid of the satisfaction of self-realization.

Young kids want to please their parents, this I postulate as a fact here. Complicated, maybe, but another discussion. The most common start of a prodigy is simply parents or other important adults praising the kid for whatever they happen to naturally do. Praise is what ignites the natural talent. Mozart didn't play the violin because "he liked it". He probably did though, because by playing well, he received praise. Self-realization is not prominent on a 5-year-old's hierarchy of needs.

> Making good art requires having a long attention span and an appreciation for the thing-in-itself

As for art, the traditional source of praise would be a mentor of sorts, an older master or a sensei. It could be your parents, but... let's just say, I beat my dad in chess when I was 6, and I didn't much respect him since, intellectually (later I've learned to appreciate different kinds of people, but kids can be like that). If you're lucky, your parents are your artistic masters as well (like for Mozart), but it's by no means necessary: the sensei can be any adult person taking note of properly ignited natural talent.

The positive feedback loop then shifts naturally from praise from parents (who will praise you, really no matter what you did) to praise from the masters. And the masters, knowing what True Art™ is, only dish out praise when the apprentice's work approaches that vision. And when the artist surpasses their masters, this way of working has already been ingrained: chasing a vision, appreciating the "thing-in-itself", even if now it's your own vision and you no longer need that feedback loop.

The feedback loop may just as well be money: you do it, you get paid, you indulge your passions in your free time. How many senior software engineers go to the work every morning for the thing-in-itself?

The feedback loop may be praise from the public, stroking the need for validation that many young people have. When a 13-year-old video maker breaks in Youtube, the positive feedback loop is a mass of people (who have no natural reason to care for the well-being of the video maker...), and while this may work just as well as "directed praise", the dynamic and also the end-result are going to look very different.

I can imagine it's common that an 8-year-old would watch the 13-year-old tube celebrity and develop a sort of "virtual older sibling" relationship, much like with the pop idols of the past. With the added bonus, of course, that the idol will actually answer their comments and read out loud their chat messages (unlike the past pop idols who would receive a million letters, handled by their managers). The feedback loop then becomes a 13-year-old stroking the feel-good receptors of a mass of 8-year-olds. I can imagine this – instead of developing a direction towards a vision – simply running directionless in a spiral that occasionally bumps to limits of moderation, laws, or propriety.

I've made this point before but our era reminds me of Paris as described in 19th century novels of Maupassant, Balzac. The promise of riches, ambition, social mobility -- if you think about it, there is an unprecedented amount of people in content creation, podcasting, YouTubing, etc, from lower class backgrounds; unlike the 20th century, where career tracks were more rigid. This possibility of social mobility makes status more visible. Conversely, downward mobility is stronger as well, and many nominally elite find themselves in a lower social class than their class of origin.