Conservatism doesn't make people happy, but conservative brains do

Causation from mental health to conservatism is not off the table, however

Conservatives reporting higher levels of mental health could be due to self-report biase, demographic differences (e.g. age, income, sex), causation, or overlap due to common causes.

Some of these theories can be easily refuted, like the demographic differences theory:

I don’t like the self-report theory because it seems to be motivated by partisanship — conservatives claim that the liberals are over-claiming their mental illnesses, and liberals claim that the conservatives are lying about how healthy they are. The differences in mental health between the two groups are also evident in everyday life. There’s some studies that try to test for the self-report bias theories using differential item functioning, and find no evidence of bias (see Kirkegaard and Cremieux). Personally I doubt the method works, but I don’t think the results are without merit.

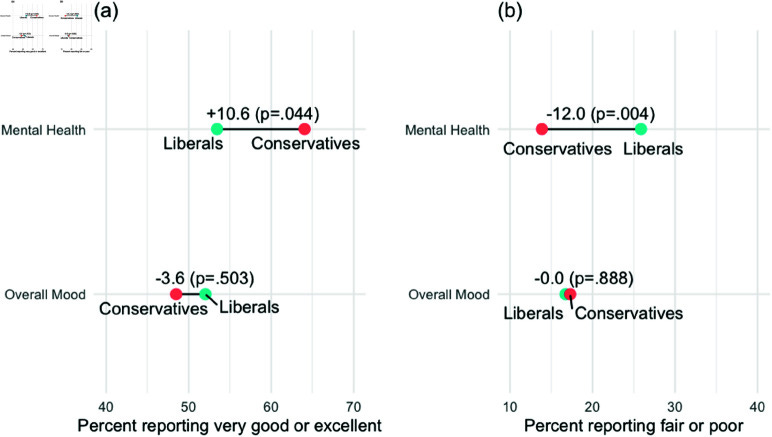

That aside, the best evidence for the difference being motivated by self-reporting is that conservatives and liberals report different levels of mental health, but similar moods:

The authors argued that this was evidence of the relationship being a function of self-reporting; the problem here is that mood and mental health are not the same things: somebody in a really good mood could still have bipolar disorder, for example. I would have predicted prior to seeing the data that conservatives have better moods, though this is by no means a refutation of the existence of a true difference.

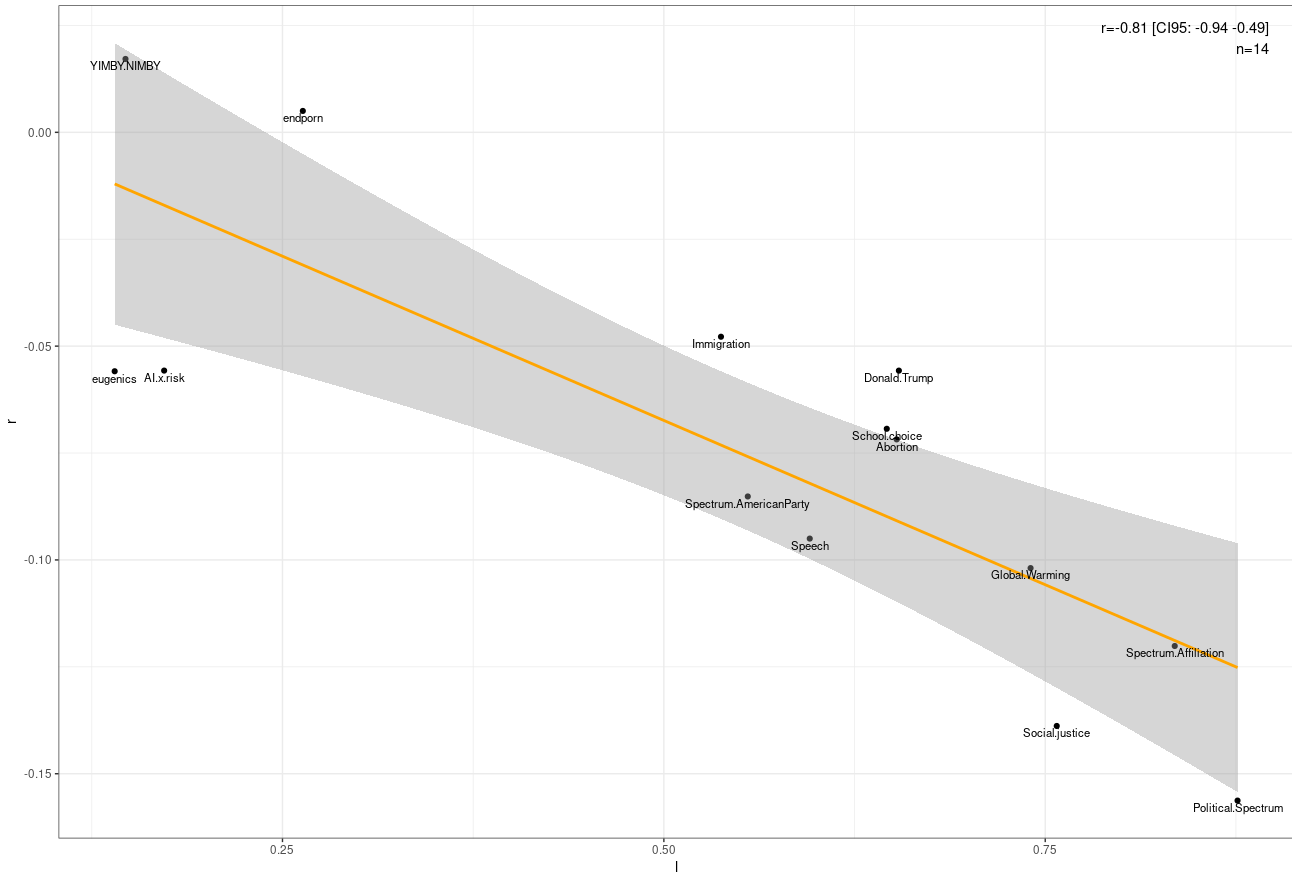

I also tried testing whether the relationship between general psychopathology and right wing beliefs was an artefact of item-level data using the method of correlated vectors, which tests the correlation between the general factor loadings of variable 1 (say, intelligence) and the correlation of those items with a second variable (say, education). The idea is that if there is a correlation between these two vectors, then the two constructs are related because of the general properties that the items of variable 1 are measuring.

I tested the method of correlated vectors in both directions, and I found that questions that loaded higher on the general factor of conservatism were more negatively associated with mental health, and that questions with higher loadings on the general factor of mental health correlated more negatively with conservatism. Both of the correlations were strong and passed statistical significance by any conceivable margin.

Given anecdotal experience and the MCV findings, I am inclined to believe that the relationship exists and is not an artefact of self-reporting. That leaves causation or the common causes theory.

I don’t think the causation goes from conservatism to mental health — conservatism is a tendency, not a belief — and whether a political belief predicts mental health is largely a function of how well it measures how conservative people are. The association between conservatism and mental health is fairly uniform within demographic groups, which is not as consistent with a causal model — perhaps conservative beliefs could make men feel better and women feel worse.

I often find that correct beliefs make the world a more predictable place, but I don’t think that is as true for political beliefs. Partly because many of them are not relevant to people’s lives, and partly because many political beliefs are prescriptive in nature. There are papers that try to test whether conservatives are more happy/satisfied than liberals when controlling for a set of beliefs1, and some of them find that these beliefs account for the difference, but this could easily be an artefact of self-reported conservative beliefs more accurately measuring conservatism than self-reported conservatism2 .

That leaves the last two theories: causation from mental health to conservatism or the common causes theory. To my knowledge, the first person to contrast these models was Hatemi:

Hatemi reports that findings are more consistent with the common causes model: the correlation between personality traits and political views is mostly genetic, but partly environmental3 and the observed effect of self-reported personality on political views disappears when controlling for prior reports of personality.

The longitudinal model has also been applied to mental health and conservatism, which found that conservatism did not cause mental health. This can be seen easily from their correlation matrix, where the association between conservatism and mental health does not depend on when the measurements are taken:

(Edit: their models did find that conservatism did not predict well-being over time, but that their results depended on study; in the first one, life satisfaction predicted conservatism, but in the second one, conservatism negatively predicted life satisfaction. In their cross-lagged model in study 1, they found that life satisfaction increased conservatism and depression lowered conservatism. h/t Norman Angleson).

Relevant sections of the text:

In summary, and consistent with Study 1, Study 2 showed no significant cross-lagged correlations where conservatism predicted a higher level of well-being using three indicators in a four-wave longitudinal dataset. Specifically, we did not find associations between conservatism and depression, and health status over time. Furthermore, conservatism predicted life satisfaction, but this association was negative—and not positive, as we had predicted. Nevertheless, when using the same analytical approach as in Study 1 (i.e., CLPM), we found that life satisfaction longitudinally predicted more conservatism, and depression predicted less conservatism, which is not consistent with the order we had predicted (i.e., conservatism did not longitudinally predict higher subjective psychological well-being).

In this research, we sought to contribute to filling this gap in the literature using two longitudinal datasets. Importantly, our analyses captured multiple dimensions of subjective well-being, including life satisfaction, anxiety, depression, and health status. Contrary to previous findings (e.g., Napier & Jost, 2008; Schlenker et al., 2012; Subramanian & Perkins, 2010), our results showed that conservatism did not positively predict well-being over time. Most of these associations were nonsignificant, especially when considering anxiety, depression, and health status. Those associations that reached conventional levels of significance indicated that life satisfaction predicted conservatism (Study 1) and that conservatism negatively predicted life satisfaction (Study 2). Importantly, these results differed from those obtained when using the first waves in both studies. Crosssectionally, conservatism predicted greater life satisfaction, lower depression, and higher health status in Study 1 and not in Study 2—but only when not including covariates. These results are different from those in the extant literature that relies on large datasets such as the World Values Survey, which includes a wider array of countries and higher sample sizes, but also includes fewer and less elaborate indicators of psychological well-being (e.g., Napier & Jost, 2008; Stavrova & Luhmann, 2016).

Technically, the existence of a longitudinal association between conservatism and mental health could be a function of the common causes changing over time — which leaves causation from mental health to conservatism left standing.

Conclusion

I tabled the implications the 8 observations have for each of the four theories:

The fact that the gap exists in all demographics easily refutes the demographic differences theory4. It’s less consistent with the bias and causality models, but not a complete refutation of them. The fact that the association exists even after accounting for bias in items using DIF is strong evidence against the self-report theory, but whether the method actually works is up for debate.

The MCV results are consistent with the association between mental health and conservatism being on the “general factor” of both variables. Technically, the causal model could be consistent with these results if it was conservatism itself that made people mentally stable, but it is inconsistent with models that claim that specific conservative beliefs make people happy.

The existence of a genetic and environmental overlap between the two variables is also a point against the demographic differences theory, say, if the association was purely due to race and sex, then there would be no genetic overlap between the traits in twin models. This would not be the case if the confounding was due to a demographic trait that is heritable (within twins) like sexual orientation or income.

The longitudinal evidence is consistent with conservatism not causing mental health, though I was wrong about the evidence not being consistent with the causation going from mental health to conservatism. In the case of personality, changes in The self-report bias theory would also expect people who change their political views to report their mental health in a different way, which also counts against this theory.

The common causes theory isn’t decisively confirmed by any of these observations, but it is the only theory that has not been refuted by a valid method. Technically, the path from mental health to conservatism hasn’t been decisively ruled out either, though the conceptual distinction between “mental health” and “whatever exists in your brain that causes both mental health and conservatism” is rather murky.

I didn’t read this paper (or any paper that used this method) because I think the regression ‘mental_health ~ conservatism + belief’ is not informative.

Regression to the mean fallacies, by gwern. Must read for statisticians.

I misremembered this on twitter; I thought his models suggested that the overlap was completely genetic.

Technically the association could be due to several demographic effects (e.g. sex and age), but anybody who believes this can download Nate Silver’s data and see for themselves.

Conservatives want to signal strength, while liberals want to signal weakness. The problem is that signaling strength *actually makes you happier* and signaling weakness *actually makes you more anxious/depressed*. So it's a self-fulfilling prophecy. Sort of a "fake it till you make it" effect.

It kinda shocks me how much time and energy we've all wasted trying to convince each other of mostly unimportant political ideas.

What political perspective you hold usually won't affect the world, apart from ruining family dinner, and it doesn't really change your behaviour or happiness either. Most of the time it's all hardware.