Talent beats hard work

I started to suspect talent beat hard work when I started following esports again, most pros had more or less the same story: they got to a high rank (>98th percentile) after 6-24 months of playing and thought about going pro after they got good. If they started playing before the age of 16, they got better as they matured, and entered the highest rank by the time they were 20. Some players who took breaks, even long ones, could get to the top 200 of the ladder within a few weeks of playing.

Statistically, hard work does not beat talent. In League of Legends, account level (proxy for hours played) explains only 10% of the variance in rank; self-reports of the number of hours spent playing Starcraft explains 6% of the variation in rank; and 60-70% of the variance in SAT scores can be explained with IQ scores1.

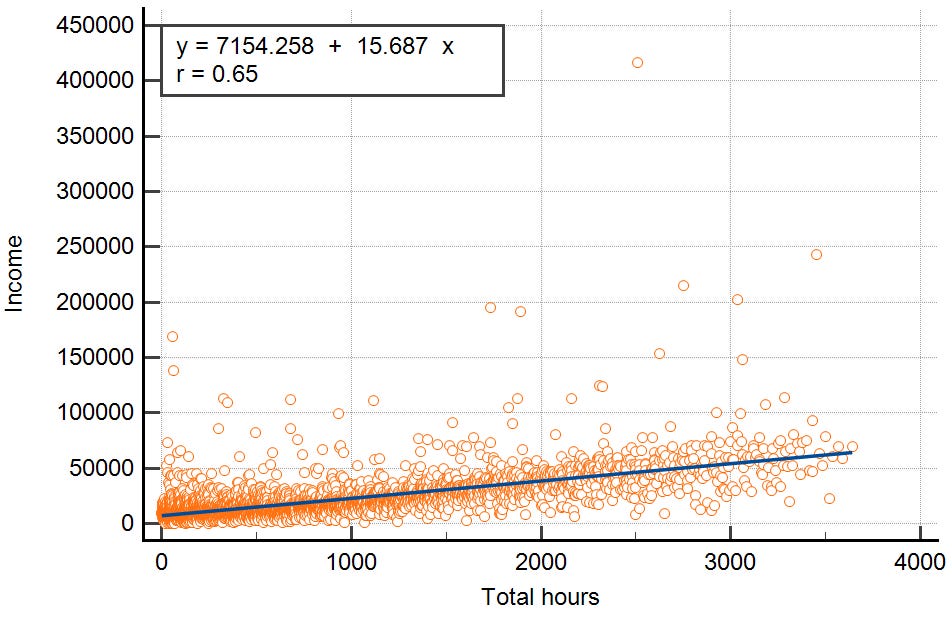

Income is a little more complicated. Cross-sectionally, hours worked in a year explains 40-50% of the variation in income within the United States:

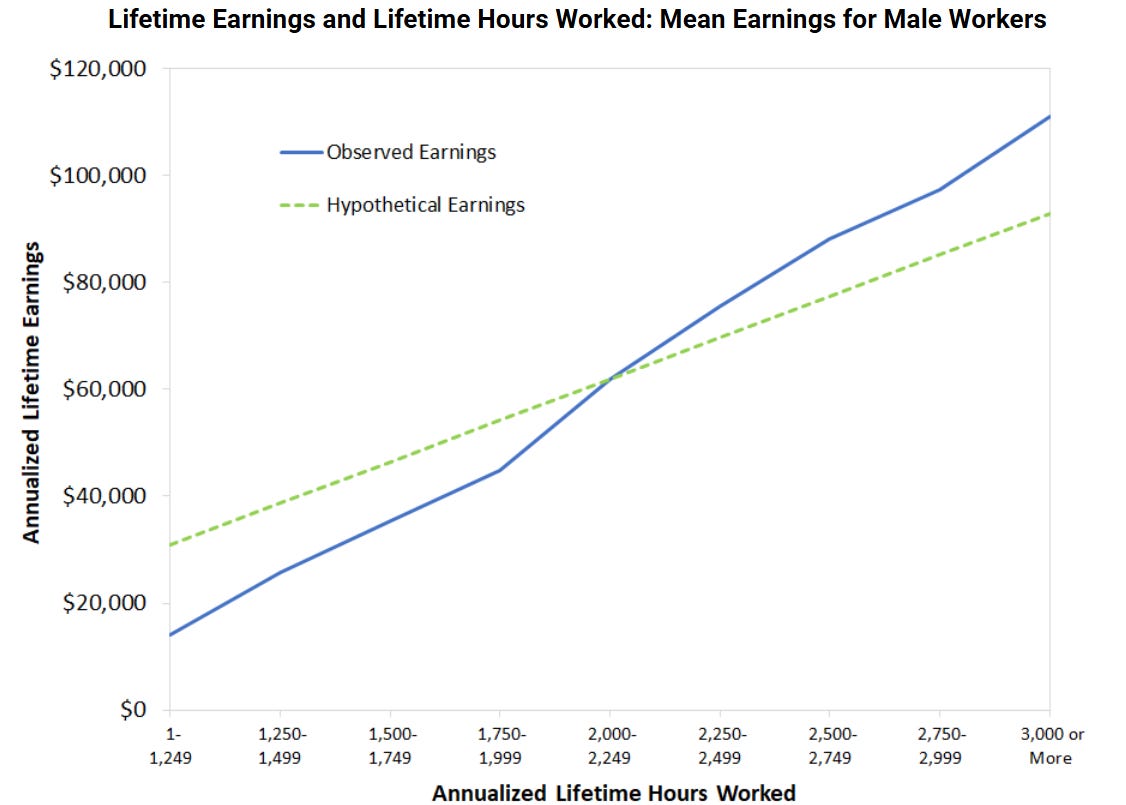

This is less true for lifetime earnings — only 26% of the observed inequality in earnings could be attributed to variation in working hours:

Bick, A., Blandin, A., & Rogerson, R.. Hours Worked and Lifetime Earnings Inequality. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. https://doi.org/10.20955/wp.2024.024

We document substantial differences between individuals in cumulative hours worked over a lifetime. We assess the extent to which these differences contribute to inequality in lifetime income through the lens of a quantitative structural model of human capital accumulation. We show that the model requires both permanent and transitory differences in preferences for work in order to match lifetime hours patterns. In addition to heterogeneity in leisure preferences, we also allow for heterogeneity in initial human capital and learning ability, as well as idiosyncratic shocks to human capital throughout the life-cycle. The parametrized model implies that one quarter of the variance in lifetime income is driven by heterogeneity in leisure preferences, and that much of this effect works through human capital investment. (Note: they restrict their sample to men with a high school degree)

I read their paper, and it looks like they forgot to square their standard deviations; assuming this is a real mistake, hours worked only explains 6.6% of inequality in lifetime earnings ( (0.19/0.74)² = 0.066 ).

Absent preference heterogeneity, our model would imply that all individuals have the same lifecycle profile for hours, human capital and earnings. Our main objective is to assess the extent to which the preference heterogeneity that we add to the model generates inequality in lifetime earnings. We find that the standard deviation of the log of lifetime earnings is equal to 0.19. In our NLSY79 sample the corresponding value is 0.74, so our model with only preference heterogeneity accounts for more than twenty five percent of overall inequality in lifetime earnings.

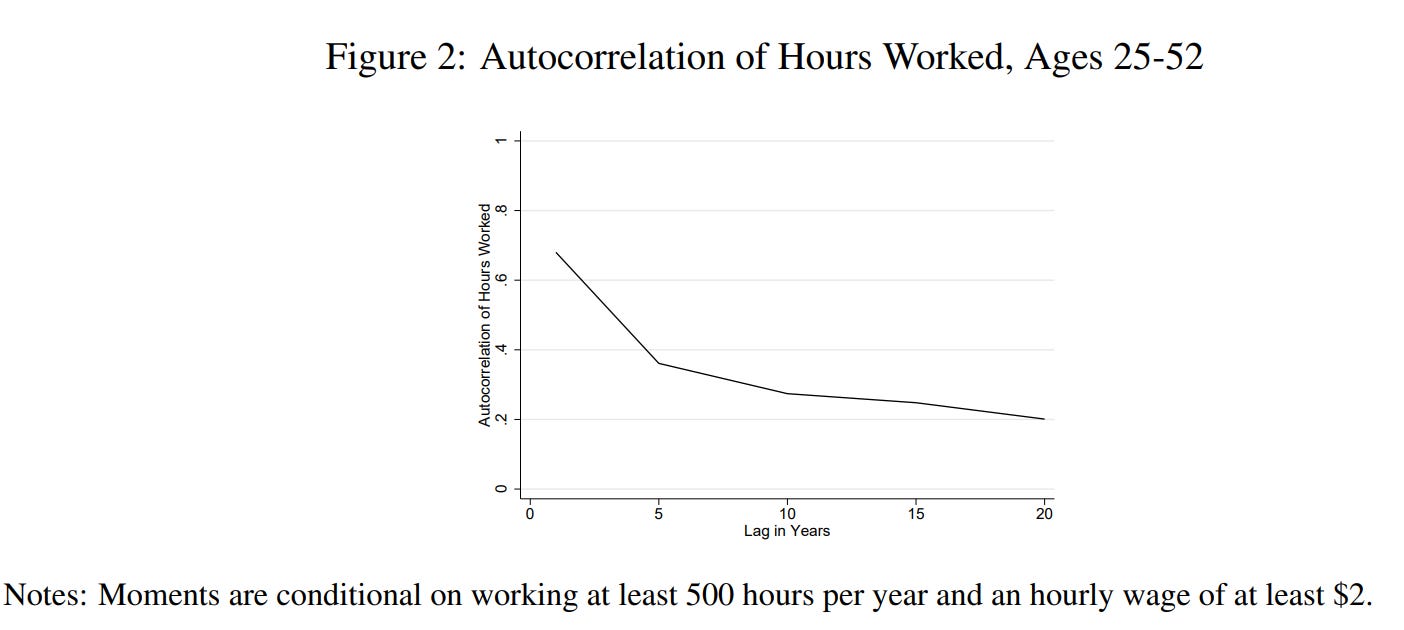

Lifetime income being less affected by working hours than yearly income is due to people’s working hours varying substantially year to year: the correlation between hours worked in one year and hours worked in the next is 0.68, 5 years later it falls to 0.38, and by 20 years later it is down to 0.20:

One could argue that hard work isn’t measured in hours, but in the amount of effort that is put into time. 20 hours of hyperfocus might be better than 60 normal ones, but the hypothesis itself is not empirically testable. It’s also not clear whether people are able to “choose” invest more focus into their working hours, or whether that is a function of unconscious cognitive processes.

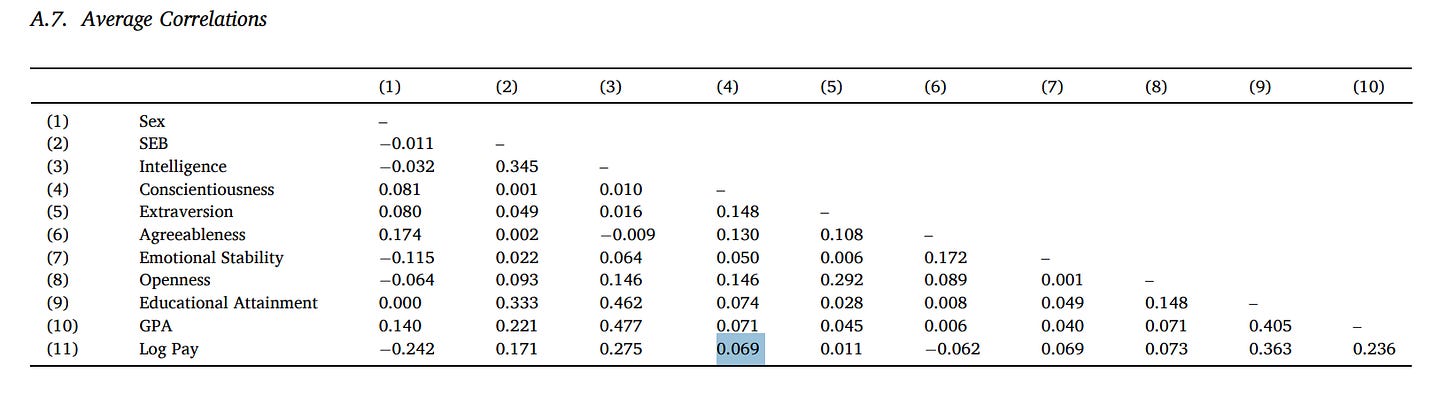

Just as time investments are poor predictors of rewards, self-reported conscientiousness only correlates at .07 with income2:

Assuming that self-reported personality has a validity of .47 and that self-reported income has a validity of .85, the correlation corrected for attenuation is .11. I assume the true correlation is higher, but I find it hard to believe that it’s much higher than that3.

Luck?

Luck matters. Sometimes people meet the right people at the right places, get sick on the wrong day, or die to hard drugs laced with the wrong stuff. The problem with luck is that it’s fleeting, like hard work in, but even more so in that respect.

Statistically, about 40-60% of permanent income is due to genetic variance, 5-20% is due to environmental factors shared by siblings, and 30-50% is due to unshared environmental factors4. One could argue that said variance explained by the unshared environment is luck, but I disagree — identical twins raised together have different heights, weights, personalities, and levels of intelligence. Luck makes us who we are.

Why talent beats hard work

One may accept that, empirically, evidence supports that talent beats hard work or see the phenomenon in their own lives, but not know why.

Consider the following diagram:

Conscientiousness has to go through two paths to get to the reward, while talent only has to go through one. Mathematically, an effect is attentuated if it goes through a mediator — in the following diagram, every effect size is the same, but the effect of conscientiousness on rewards is 0.49 (0.7 x 0.7).

Evidence for the feedback-loop theory can also be seen in the lifetime earnings paper: people who work more hours have higher earnings beyond what would be expected from the effect of working the hours themselves:

A conscientiousness person who gets no rewards due to a lack of talent will eventually wear out, while the averge talented person will be more incentivized to invest into their skillset. I never understood why people contrasted the two concepts — conscientiousness is as innate as any other personality trait — therefore one could argue that hard work itself is a talent. But now I get it: talent makes work easier, but hard work doesn’t make talent.

The R^2 vs r debate is meaningless. At the end of the day, 10% of variance in y being explained by x means that 90% is explained by something else.

In the paper I cited, the personality measurements come from surveys not administered by employers, meaning the results cannot be blamed on self-presentation during the hiring process.

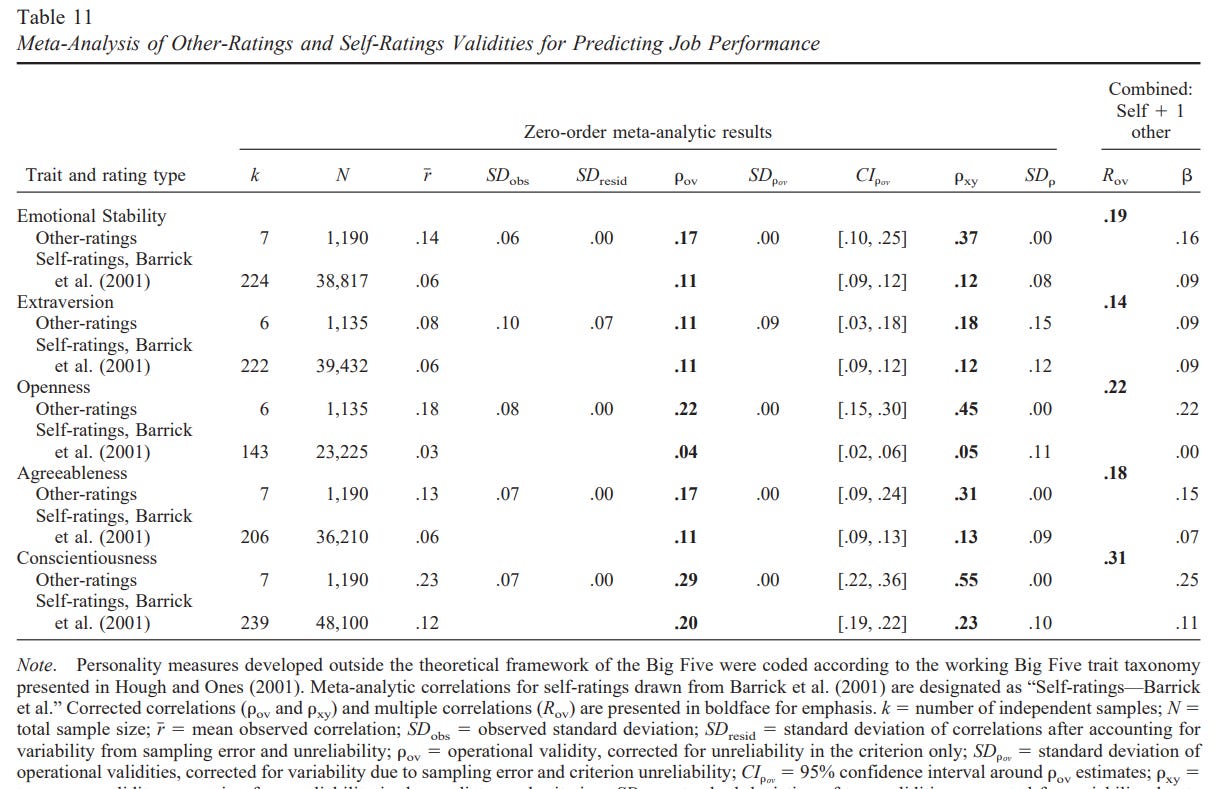

There’s one paper that finds that peer-rated conscientiousness is better at predicting job performance (r = .55) when correcting for attenuation, which is pretty good, but still leaves 70% of the variance unaccounted for. Their correction also assumes that peer-rated conscientiousness is only correlated with job performance only insomuch that it correlates with true conscientiousness, which is an untenable assumption — I assume people infer how conscientious others are based on how they behave.

I also have no idea how they got from .29 to .55 in their correction for error, when the correlation between self and peer ratings of conscientiousness is .44 according to the paper ( .29/sqrt(0.44) = 0.44 ).

My guess is that the true correlation between conscientiousness and lifetime earnings is 0.35 (changed mind).

Hyytinen et al and I estimate a similar heritability of permanent income, but I think their paper downplays the role of the shared environment; based on different pairs of relatives reared apart vs together it clearly explains over 5% of the variance, perhaps even as much as 20%.

Talent stratifies people. Hard work sorts people within strata, or might move someone on the edge from one level to the next.

Seems obvious if you pay even a little attention to your peers. Good post.