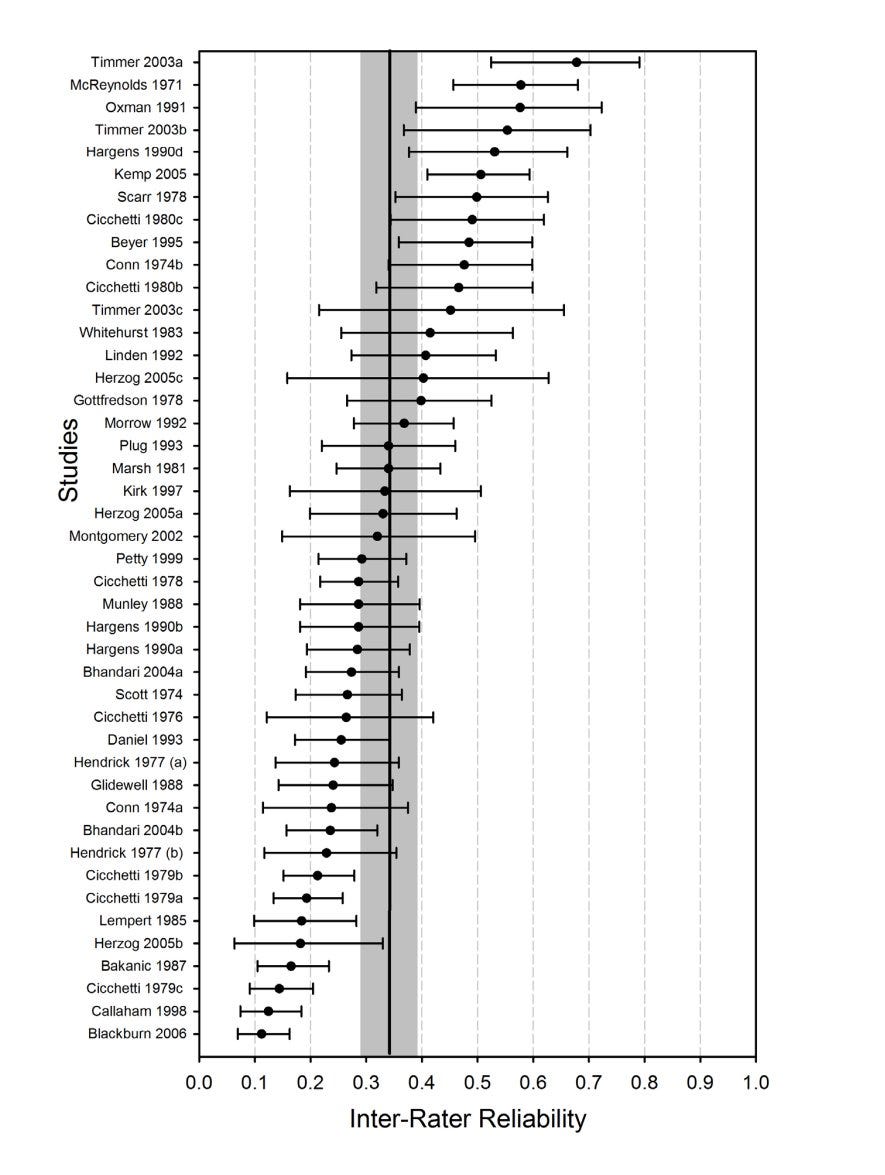

I think my favourite statistic in the world is that the inter-rater reliability of peer reviewers is .35, which qualifies as “poor” or “questionable”.

It’s not clear to me exactly why anyone would think peer review is good at quality control. Two guys who may or may not know the topic at hand, and may or may not care about doing a good job are tasked with critiquing1 a paper.

I’m not sure why peer review caught on, whether it’s having a mechanism that prevents people from publishing a ton of super low quality papers to boost metrics, or whether people noticed that papers reviewed by peers tend to be better and therefore made it mandatory. I don’t think it matters. People are trying to bolster the process with more technique (e.g. blinding, more reviewers, public review) but none stand out as particularly helpful. The process is also tedious.

Incentives

People primarily try to get into academia because they like the job itself, are into ideas, want money, or strive for status. People may be motivated by several of these drives, but often one dominates. To become tenured (free), professors have to publish papers that get cited and keep a clean reputation.

Sometimes professors cheat. The most common method is p-hacking: getting a dataset, fishing for an association that reaches p < .052 or even p < .01, coming up with a post-hoc theory as to why it exists3, and publishing it. Some people understand this is a problem and have tried to implement norms to avoid this, such as forcing public code/data, conducting preregistrations, or correcting for multiple testing.

All of these methods are flawed. Some studies can’t really be preregistered (e.g. studies that track inceldom over time) and even then sometimes preregistered studies fail replication. Open code can still have issues running on other people’s computers and correcting for multiple testing isn’t possible if the authors can selectively present their findings.

I call this phenomenon the cycle of tragedy: some people find some way to cheat the system, some people find out the method exists and patch it, the effectiveness of that cheating method decreases, and so on. Adding these rules makes it harder for people to cheat and publish legitimate research too. Not to mention how much more difficult it makes it to get into academia as a newcomer.

The process of studying and learning is something that is best done unconsciously and genuinely; one cannot force sustained interest in abstractions. The anti-cheating protocols involved in publishing things results in more academic labour being conscious, which decreases people’s productivity and satisfaction with their work.

The academic protocols that people would agree to in the age of the internet/LLM would also be very different. Lengthy introductions that flesh out the topic would no longer be encouraged as reviewers can just look up concepts they do not understand or request a summary from an LLM; discussion sections would be less valued for similar reasons.

These problems leave academia populated by different types: personally I see the narcissist, autist, nerd drone, and impostor the most. By “narcissist” I don’t mean a selfish person4 who likes being special, I mean a person who can’t differentiate themselves from their surroundings and devolve into hyper-confident or hypo-confident behaviour depending on their temperament, often seeking external sources of validation and value.

Some time ago I tried researching the group selection question and found it tedious as all people wanted to argue about was altruism and racism. Predictably, altruists and racists like the idea of group selection while Randian individualists don’t. I suspect that group selection does happen, but not in the way people think it does: some psychological types are better for the group (e.g. hero, everyman, genius) while others are detractive; I suspect the narcissist is the type that drags down groups the most.

Over time, the average intelligence of an academic has definitely decreased due to the education system being less selective. I actually don’t think the decreased intelligence itself is that much of a problem, intelligent people can work on their own or with each other if they wish, the issue is that decreasing the barriers to entry of academia has opened it up to the striver class and caused the rule and regulation cascade.

Where does academia go?

I am doubling down on my prediction that academia’s prestige will nosedive in 50 years5 for reasons I outlined in a prior post: lack of progress, lower trust, rise of AI, worsening demographics, and the decreasing selectivity of academia.

The silver lining is that if academia’s prestige reduces, then the strivers will leave, opening up the doors to people who like ideas or just want a job again. It will take a while for people to start up a new way of doing science that doesn’t involve all of the weird rules that we used between 1950 and 2050, but I have faith.

The only reasons I would recommend getting into academia are using your status as a professor to publish books and get onto talk shows, dating hot female (or male) students, getting tenure and proceeding to do absolutely nothing for the rest of your career, and doing important work like GWASes or metascience.

All critical things are bad.

The “p” here refers to a p-value, the probability a statistical association as or more extreme than the one that was found would be observed under the null hypothesis, which is (usually) the absence of a true statistical association. “p < .05” refers to the p-value being under .05, the cutoff where people conclude that their association is (probably) true.

It’s important to differentiate tinkering (good) from p-hacking (bad). See Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge for more information.

I blame The Last Psychiatrist and Lasch for this conception of narcissism.

15 more years for the millennial + zoomer cohort to wreck havok on the institutions and 35 more years for the generations that grew up with high status academia to be replaced.

I would like to see models of the net benefit of forging credentials. How easy / expensive would it be to forge a PhD? You have the easiest method, which is to claim it on your resume and hope the interviewer doesn't bother checking or googling. Then you have the next level, which is to purchase a PhD from a fake university. Then you have the next level, which is literally to pay a person to do all your PhD work for you.

Assuming that getting a PhD requires 20 hours of work over 4 years, 8,000 hours, I assume that would cost $80,000, plus the cost of enrollment (although some programs actually pay you a stipend). For each of these methods (maybe there are additional methods), what is the cost, risk, reward? Can we quantify the value of a PhD as $10,000 per year, and say that these methods pay off in 8 years?

Let me try to understand what you're saying: strivers infiltrate academia, they make up fake studies, then academia must try to stop them, which hurts real research. If you just let fake studies proliferate, trust plummets and the value of research approaches 0. If you introduce tests of fakeness, you decrease the production of real studies as well. Barrier to entry.

Ideally, there would be zero barriers to entry, so that as much research could be produced as possible. But without barriers, there is a problem of pollution, where fake research is being produced.

Maybe the problem is that we are too risk averse, and too afraid of fake research. If academia was a free-for-all where anyone could do anything, yes this would produce a lot of fake research, but it would also produce more innovative/creative and ultimately productive research. We shouldn't punish the productive for the sins of the striver.

This seems to be a problem of perfectionism, of maximizing efficiency over total output, which is itself part of the striver package. The problem isn't that strivers exist within academia, but that they dominate it, and it is their mindset which drives increasing peer review. Strivers are, first and foremost, concerned with status, so their entire psychology is built to prevent reputational harm -- which peer review is meant to stymie.

The solution I believe is to introduce personality tests to prospective students to select for higher risk taking, with more intense testing for administrators. My assumption is that sports correlate with risk taking (testosterone), but there might be better ways to test this.

"It’s not clear to me exactly why anyone would think peer review is good at quality control."

Existing in blissful ignorance of both human nature and their own, human, nature, is enough to also be unaware of what ćpeer review" must forever end up being like, and doing.