Contra Lyman Stone on national IQs

Emil Kirkegaard, Bryan Pesta, George Francis and I did a meta-analysis of dysgenic fertility across the globe a year ago:

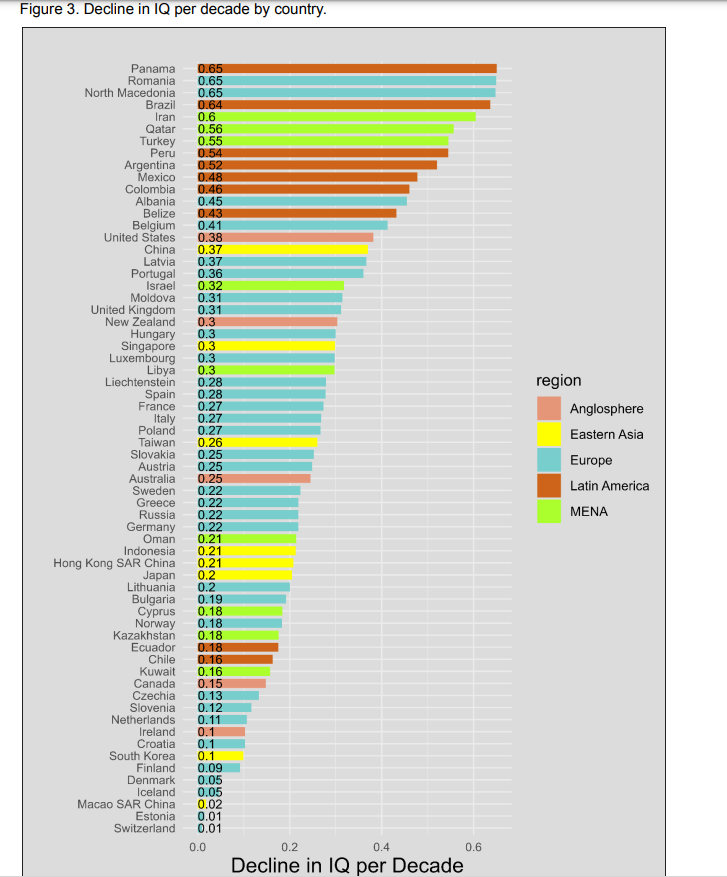

Research on the relationship between fertility and intelligence, while extensive, is mostly limited to the United States.The existence and magnitude of differential fertility could vary depending on the region and the country; however, this area of research has not been explored. To overcome this limitation, the magnitude of the selection differential for intelligence in 65 different countries was calculated by consulting the literature and analyzing international datasets (n = 419,444, k = 156), as well as the magnitude of the correlation between fertility and educational attainment (n = 797,455, k = 454). Based on the results of the meta-analysis, the average country’s IQ is declining by 0.35 points per decade. Region comparisons suggest that the relationship between the number of children and intelligence is strongest in Latin America, Iran, and Turkey. In Denmark, Iceland, Estonia, Finland, and Switzerland, intelligence and fertility are negligibly related. However, there were some concerns with the quality of the international data which put the latter finding in question.

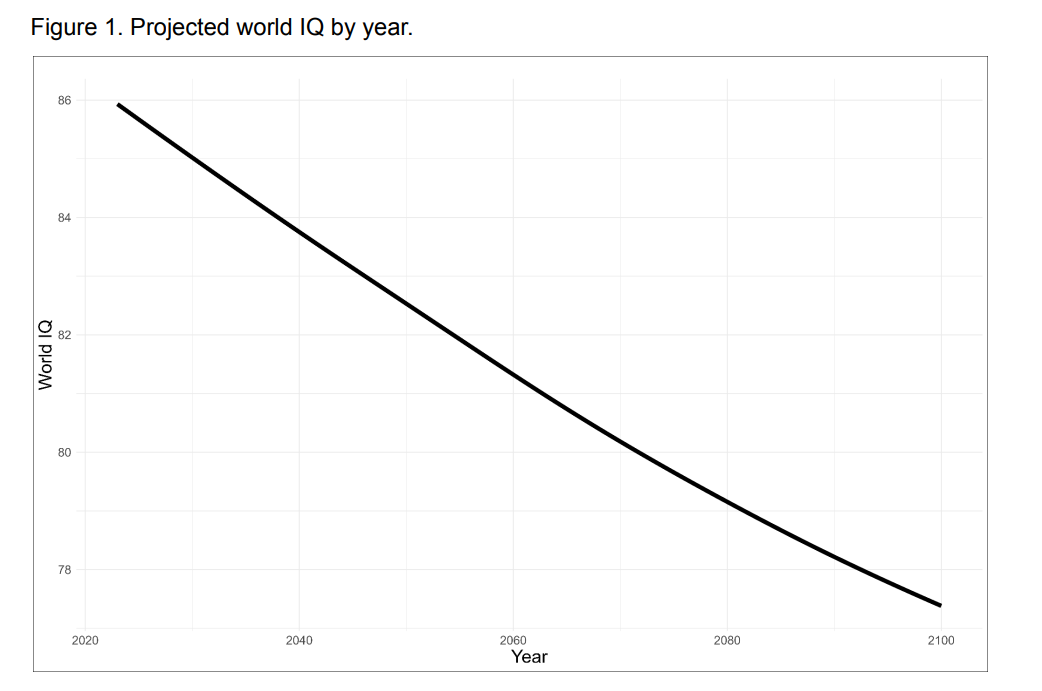

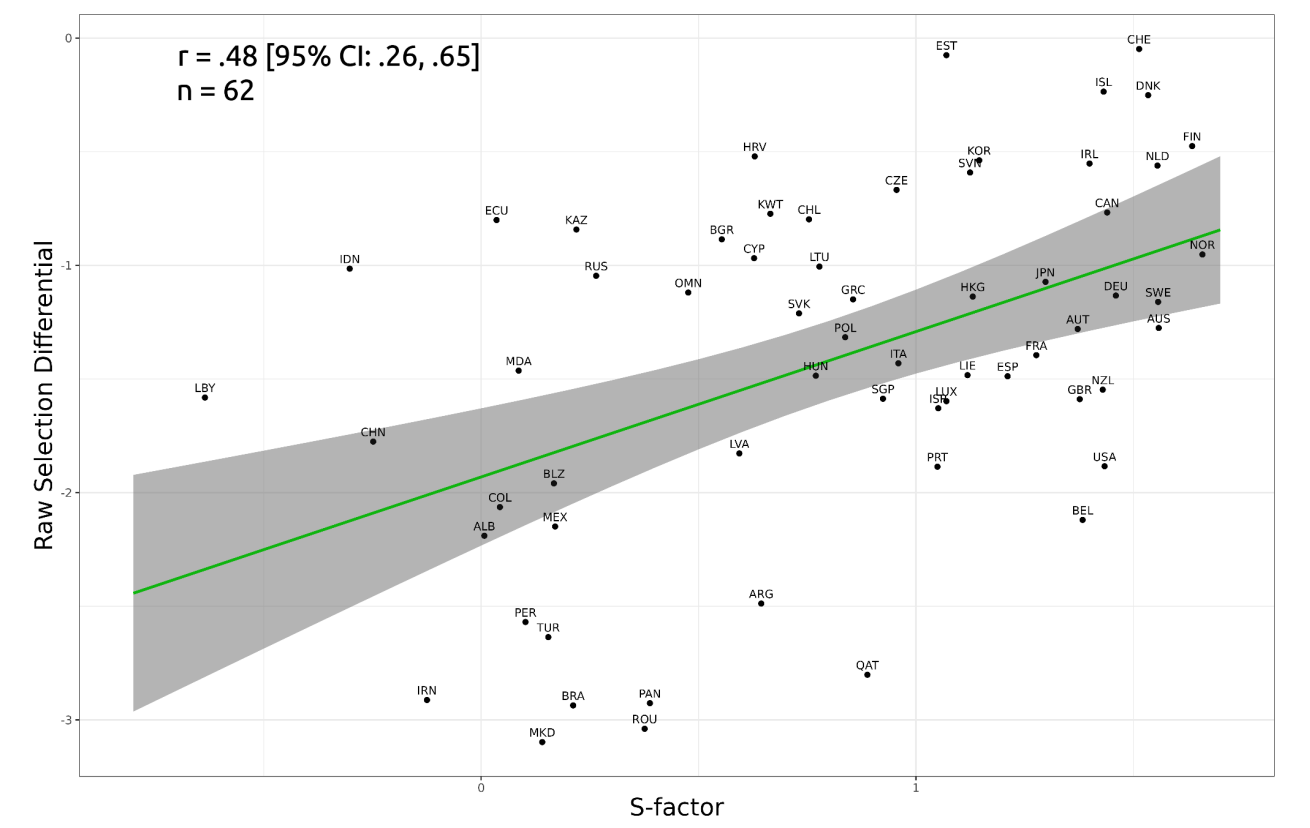

The magnitude of the decline in IQ globally is about 1.1 point per decade between the years of 2023 and 2100, though the rate at which intelligence is declining is falling. When weighted by population, the magnitude of the decline within countries is 0.4 points per decade, so 36% of the global decline in IQ is within countries. National IQ and the selection differential for IQ correlates at 0.51, while socioeconomic development and the selection differential for IQ correlates at 0.48.

This is the projected world IQ by year:

Alternatively:

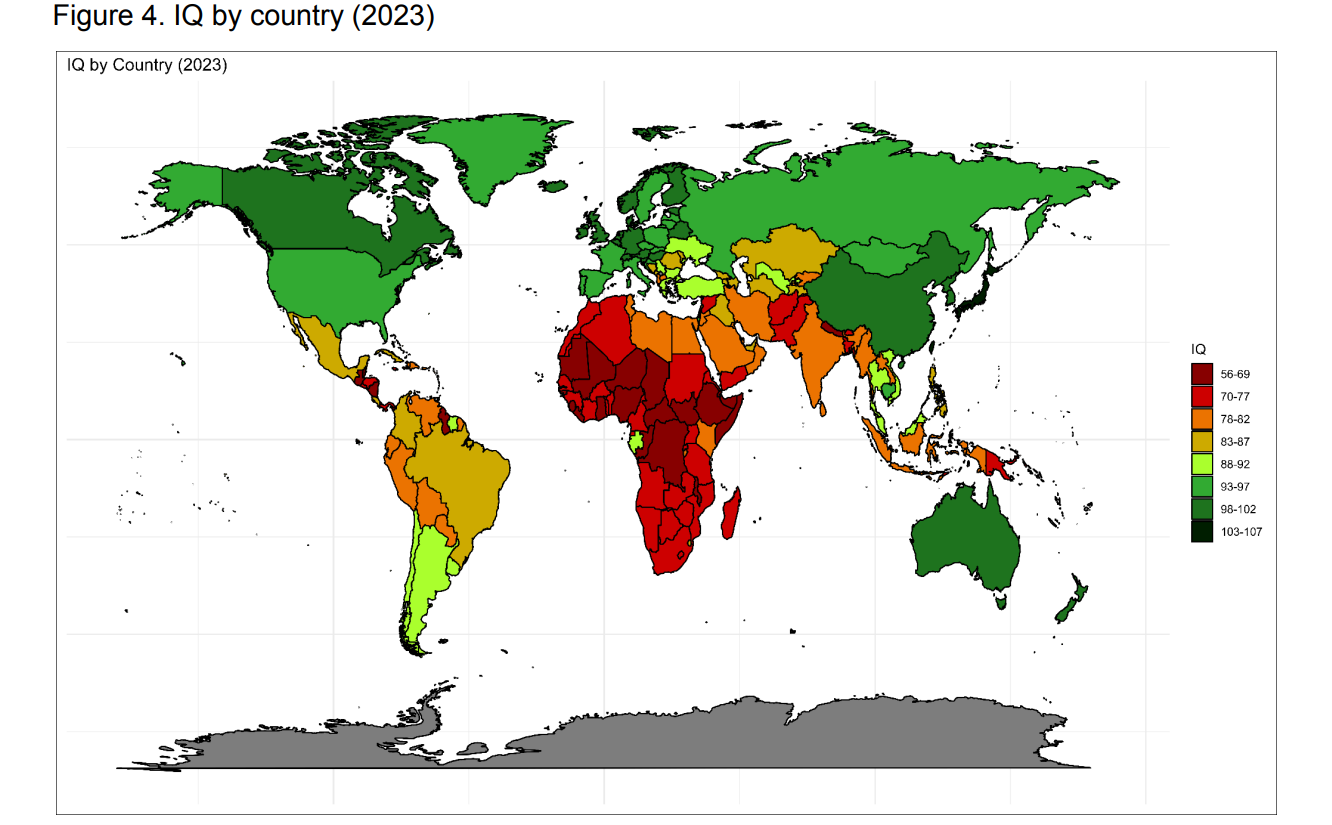

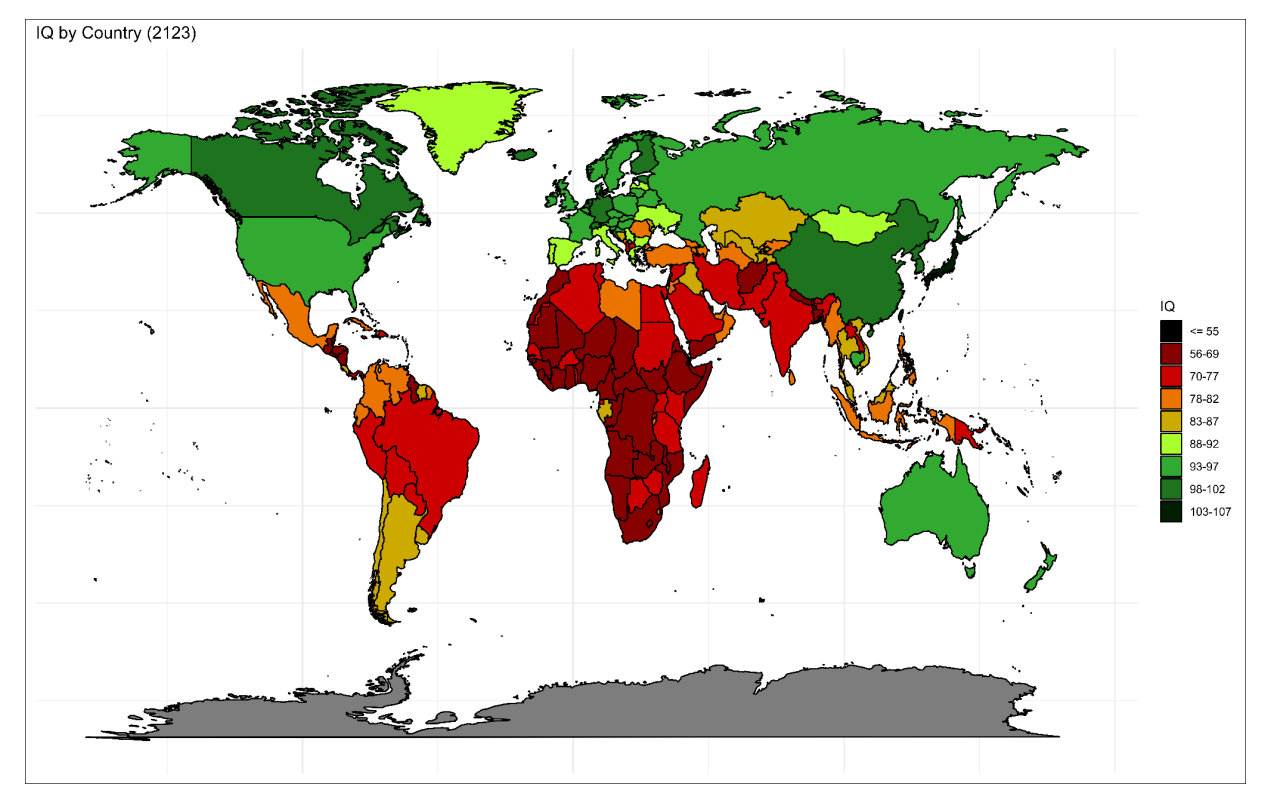

Most developed countries are going to be fine in the next 100 years, but they are going to have smaller populations, meaning less cultural and technological elites that can drive progress. If the dysgenic fertility estimates of developing countries are accurate (which I have doubts about, but more on that later), MENA and Latin America will be as intelligent as Africa in one century.

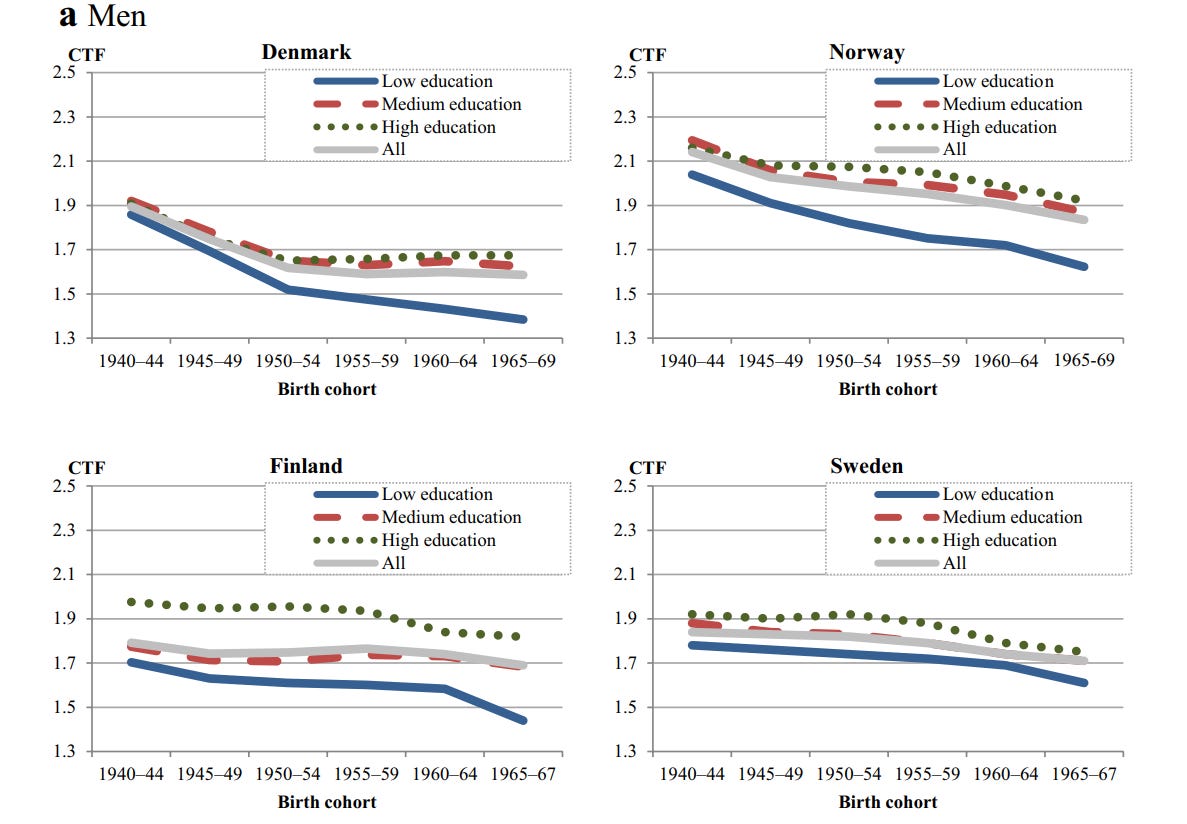

Most of the decline in global IQ is between countries, not within them. Developed nations tend to have weaker relationships between intelligence and fertility, which is why they are expected to have smaller declines:

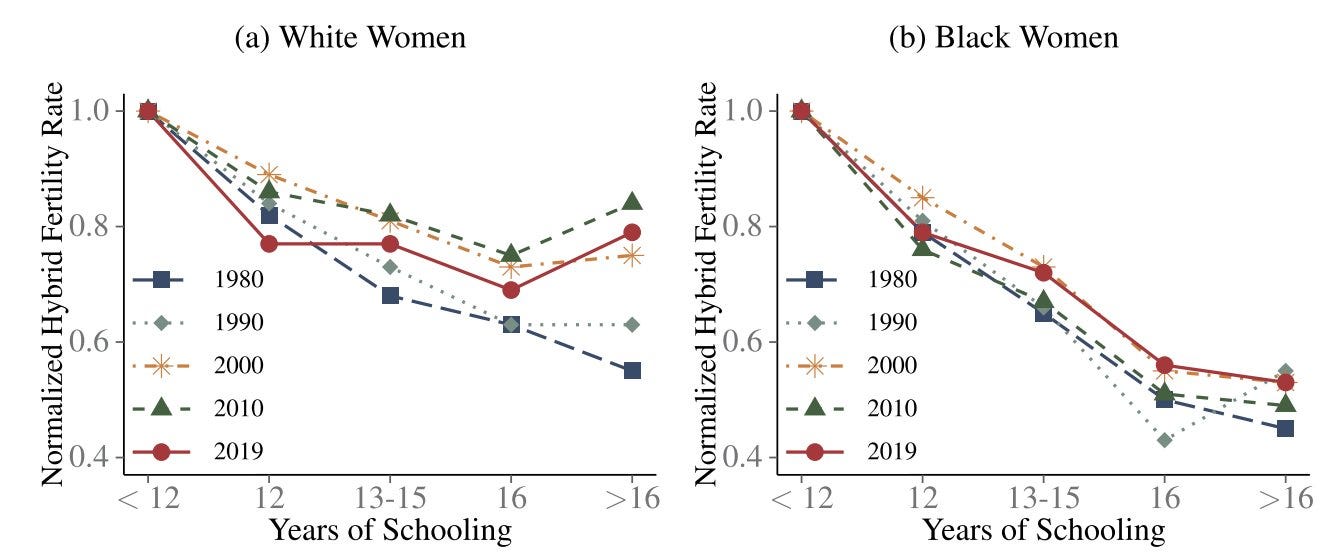

An interesting finding, but I suspect it is an artefact of less intelligent countries not having undergone the demographic transition to the same extent as the intelligent ones. Within countries, when fertility declines, typically it is the lower class in which this decline is the most pronounced:

Because of that, I think that my prior prediction of super low IQs in the developing world will not come to pass anymore, although I could see it being the case in maybe 2 or 3 centuries.

Lyman Stone, on the other hand, recently wrote a piece arguing that the existence of dysgenic fertility within societies is not as scientifically supported as people think it is.

First, he takes the position that intelligence is not that heritable.

Scholars have spilled a virtually limitless stream of ink on the question of what intelligence is, how to measure it, and whether it has any genetic component. I won’t waste time rehashing that debate here. For the purposes of this article, we will take what seems to be a reasonable middle-of-the road position. Across 50 years of research on intelligence across kinship ties that involved hundreds of studies, it appears that about 50% of human variation in cognitive traits can be explained through biological kinship. Modern genetic studies have identified numerous genes thought to influence cognitive ability, but they suggest a considerably lower degree of heritability: 20-40%. The exact numbers don’t matter here; what matters is that for this article, I’ll work with the assumption that cognitive abilities are a real, meaningful construct that have at least some genetic component. Unfortunately, the usual way geneticists measure cognitive ability indicators in genes actually is not based on genes predicting intelligence, but based on genes predicting educational attainment, which is not, strictly speaking, the same thing. Genes related to educational attainment probably are less predictive of actual intelligence than genes known to be related to intelligence.

He’s ultimately wrong, but it does not really matter in this situation. The correlation between the average IQ of two parents and the IQ of their child is about 0.6; regardless of whether this correlation is genetically or environmentally mediated, if less intelligent people have more children then future generations will become less intelligent.

Stone also notes the results of studies that track differences in genes related to educational attainment over time. He notes that there is a decline in the case in Iceland, the US, and the UK, but not Estonia and Finland.

Are Genes Related to Educational Success Getting Rarer?

The first place to look to see if dysgenic fertility could be an issue is large population genetic registers. In these big datasets of human genetic data, researchers can ask: are genes believed to predict intelligence more common or less common in more recently-born cohorts (younger people) than earlier-born cohorts (older people)? Taken at face value, these studies suggest that the genes associated with higher intelligence seem to be getting less common over time in some countries. Of five studies I could find, studies in Iceland, the U.S.,and the U.K. suggest declines ranging from 0.3 to 0.9 IQ points per generation, while studies of Estonia and Finland suggest no decline and maybe even a slight increase.

There is a fairly simple answer to this paradox: there is no dysgenic fertility in Estonia and Finland but there is in the UK and USA.

The Icelandic study he cited found a decline of 0.01 standard deviations per decade, which is consistent with the observed IQ ~ fertility correlation from the meta-analysis.

He also claims that there is no decline in American polygenic scores for education/intelligence after 1950.

First of all, virtually the whole U.S. decline occurred among cohorts born before 1950 with very little decline in more recent cohorts.

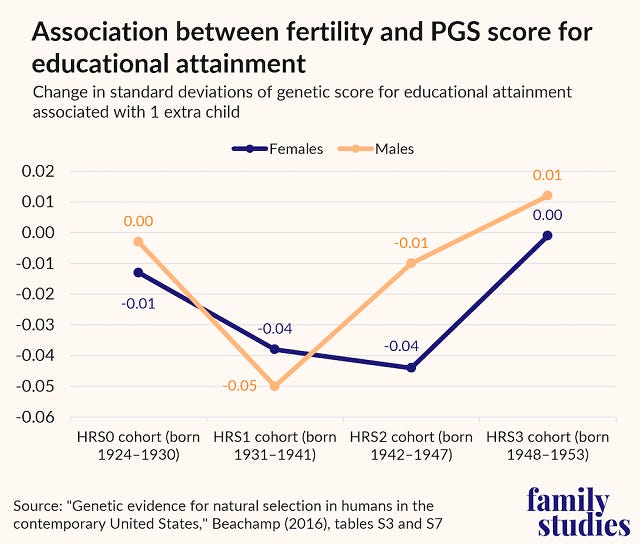

The data he cites earlier only goes up to 1953, which is an incomplete picture.

Stone then goes on to claim that genes for educational attainment and fertility do not covary in the most recent cohort of Americans.

More than that, one recent study estimates how genes for educational attainment have related to fertility across different generations, and finds that there is no dysgenic fertility in the youngest cohort (in this case, the “youngest cohort” is people in their 70s today):

The finding here is obvious. For American men and women born 1931-1947, there was probably a real negative link between the genes that predict education (largely genes related to cognitive ability) and fertility behavior.

But that wasn’t true for the 1924-1930 birth cohort, nor for the 1948-1953 birth cohort. The point is: the supposed “dysgenic” link between cognitive ability and fertility was a flash in the pan. It applied to people of a few particular birth cohorts, but isn’t generally applicable. Maybe dysgenic trends will appear again among parent generations born in the 1960s, or 1970s, or 1990s—or maybe they won’t!

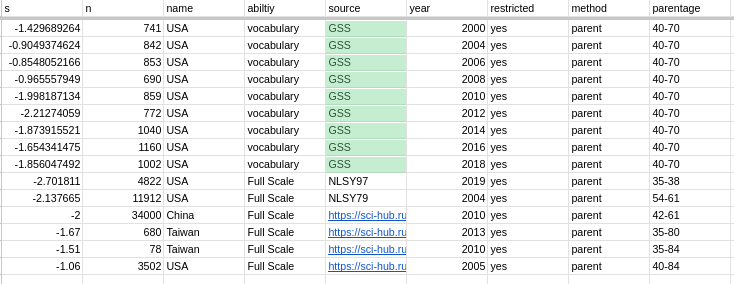

If one checks the modern years in the General Social Survey or the NLSY97, the selection differential for IQ is consistently about 2 points (assuming a heritability of 60% and generational timing of 30 years, that is a decline of 4 points per century), which is the roughly the same as it always has been. I see no reason why this should not cause the same genetic declines that were observed prior.

He also questions the extent to which the declines are universal:

These details tell us something important: there’s nothing about modern society that makes “dysgenic fertility” inevitable. The extent of any “dysgenic fertility” varies across time and space such that there is no universal rule of dysgenesis across otherwise similar societies.

Well, not it is not universal, but it is the norm in most countries, probably because less intelligent people tend to desire to have more children. The universality of dysgenics in modern society is sufficient to think it is a major issue, but not necessary, so I do not consider this a meaningful rebuttal.

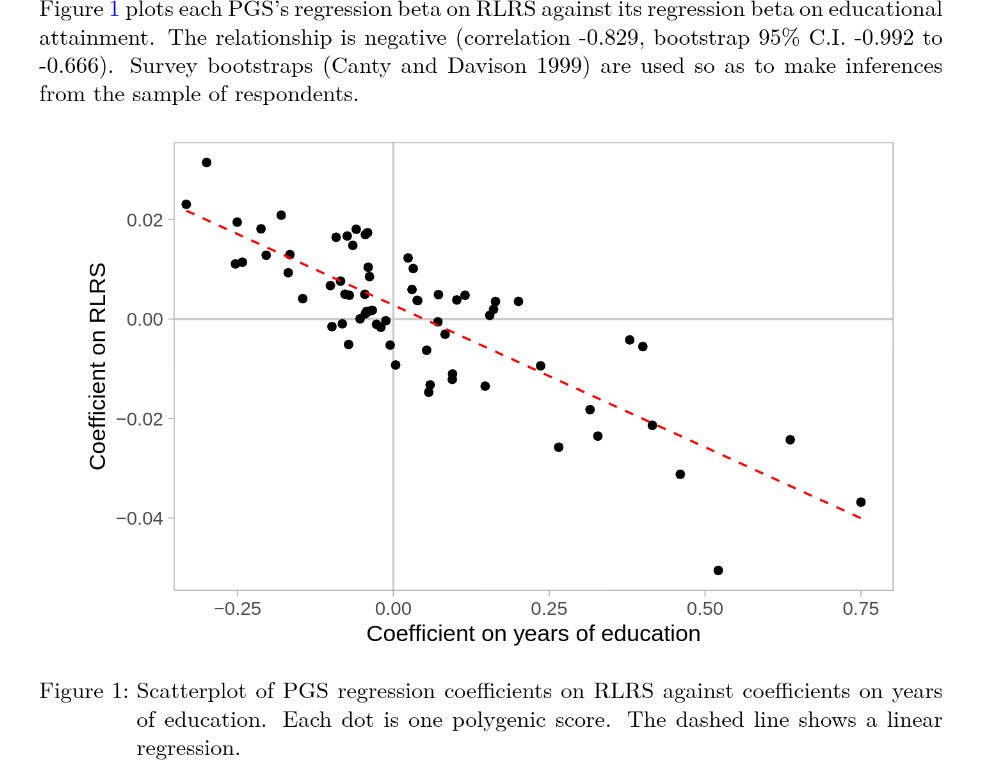

Stone then goes on to argue that it is possible that genes related to cognitive fertility may not be related to intelligence. It’s not really worth explaining why his arguments are wrong, because we have data that shows he is. Polygenic scores that are positively correlated with years of education are negatively linked to fertility relative to people born in the same birth cohort:

In terms of the big picture, I largely agree that within-nation dysgenics are overblown, but his arguments as to why this is the case are terrible, frankly.

Kirkegaard commented on Stone’s article prior to this, and argued that even if within society dysgenics are weak, the between society dysgenics are not and should be taken seriously. Which takes us to Stone’s second post on the subject, where he responds to Emil and says that between country dysgenics do not matter:

It doesn’t matter if the average human gets dumber via composition effects even while people within countries are not getting dumber.

Think about this, really, think about it! A world where Europe’s population share is 50% lower than it is now is a very different world of course, but national-level fertility rates are unstable and falling everywhere. Provided that within-country dysgenesis isn’t an issue, we would have a brief episode where humanity gets dumber, then by 2100 or 2150 everything will go back to normal. In the meantime, Africa will be much bigger, but the Congo isn’t about to build a navy capable of making an amphibious landing in Portugal or something (especially if Emil is right that the average African IQ is 70— you’re not gonna build ballistic missiles at that IQ).

The worry is that people from the low IQ countries will migrate to the high IQ ones to replace their declining populations and tank genotypic IQs, not that billions of Africans are going to wage war against the entire developed world. That’s what the Sahara desert exists to contain. I assume Stone’s response to this would be to advocate for pronatalism — independent of prescriptive concerns, declining native populations in developed countries from a descriptive perspective looks inevitable.

His major contention, however, is his skepticism of national IQs, which he wrote an entire separate post on as a response to Cremieux.

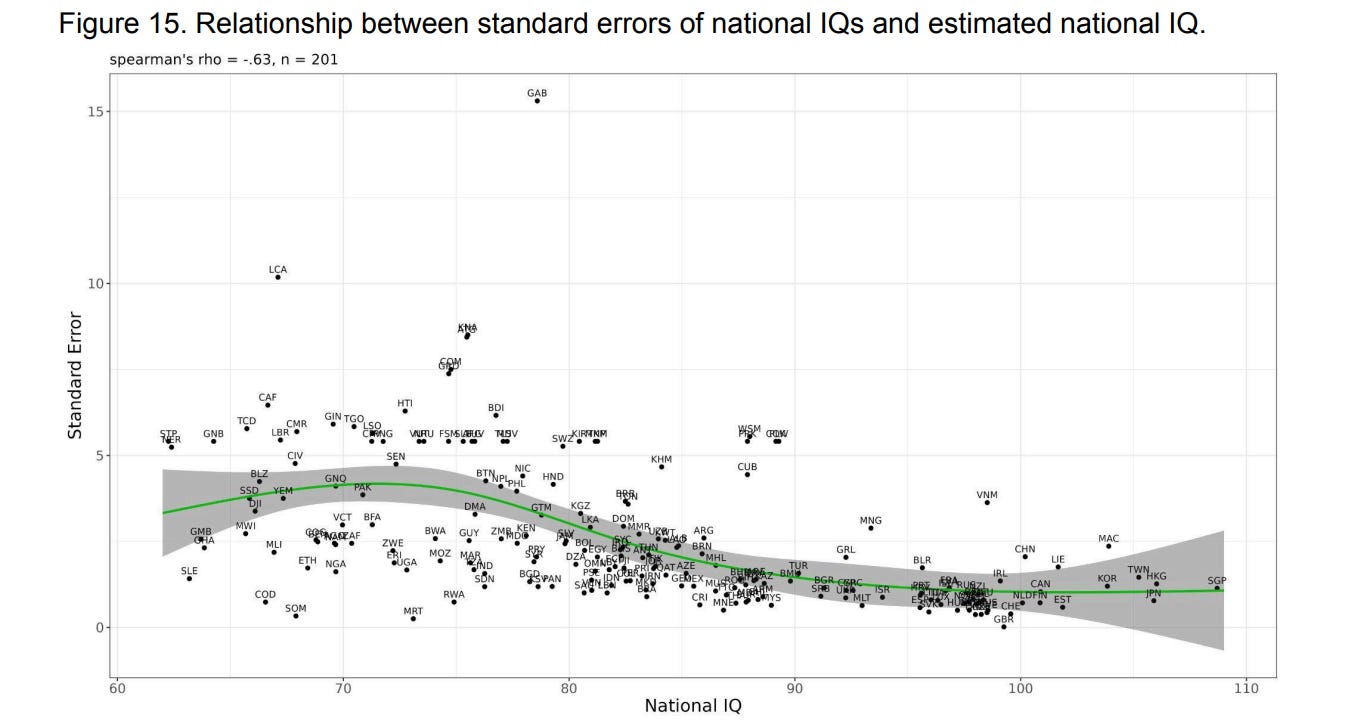

My take on national IQs is that at an individual level they are not that reliable (this is particularly an issue for sub 80 IQ countries), but that opposition to them is largely driven by midwits and moralists. On average, a sub 80 IQ country has a standard error of 4 IQ points, despite the fact that the averages are made based on overlapping data.

To be honest, I never took national IQ denialism seriously because of what is known about intelligence within countries: Asians outscore Europeans, who outscore Arabs and Latin Americans, who outscore Africans. Wealthy people tend to be more intelligent than poor people. Is it really a mystery that the same occurs between countries?

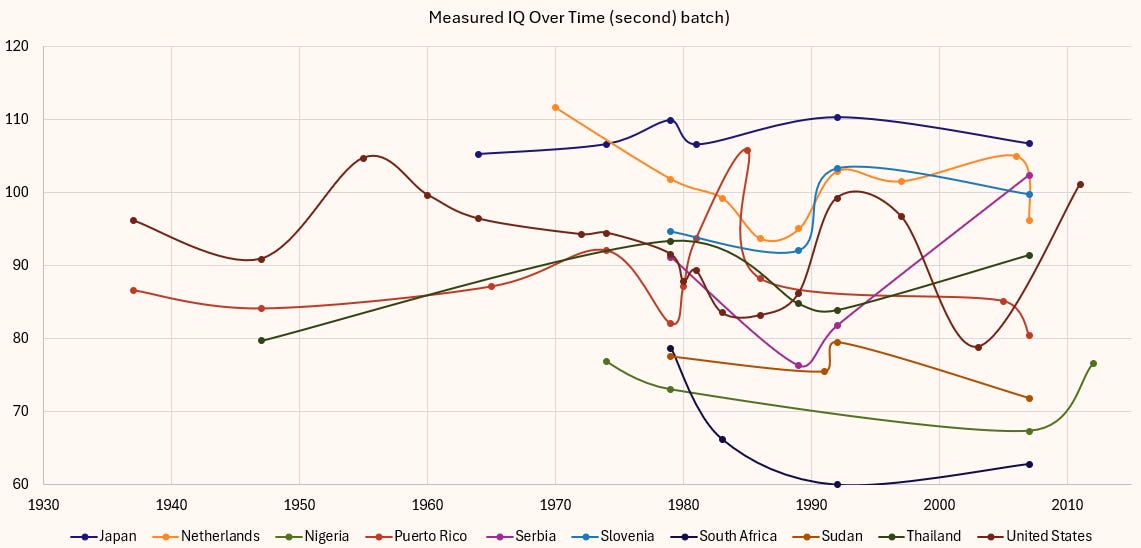

Onto Stone’s arguments as to why national IQs (probably) are not valid: his first contention is that IQ can change over time. This is not really a critique of the concept of measuring national IQs, but of the way they should be measured: perhaps scores could be assigned for every year or every decade.

He then plots the average IQ of each nation (using Becker’s dataset) by year, and shows that there are substantial changes depending on the year:

He then goes on to say that these changes are unrealistic and that they show that the dataset is of compromised quality:

Now maybe Cremieux can say something like, “Well, you have to do some extra normalization…” or “Well, the samples aren’t all quite representative, so you have to do some adjustment…”

Okay, fine. Do those and come back. I’m using the NIQ data downloaded right off the site that hosts Lynn’s data, the latest, most updated version. I made no special modifcations. And it sure looks to me like those estimates are bologna.

Here’s the problem: the reliability of individual IQ samples absolutely sucks: they vary quite a bit due to sampling error, regional differences, tests, and whatnot. Take Morocco, for example — there is a ton of variance in performance that cannot be explained by cohort differences, even on the TIMSS and PISA scores that people put more faith into.

This does lead to a decent amount of inaccuracy in the estimation of IQs — for all I know, China’s true IQ could be 95 instead of 100, or perhaps Chad’s IQ is 75 instead of 66. Fortunately, averaging these samples together results in a more reliable average, so arguing that there is considerable heterogeneity between countries does not imply that the overall averages are compromised.

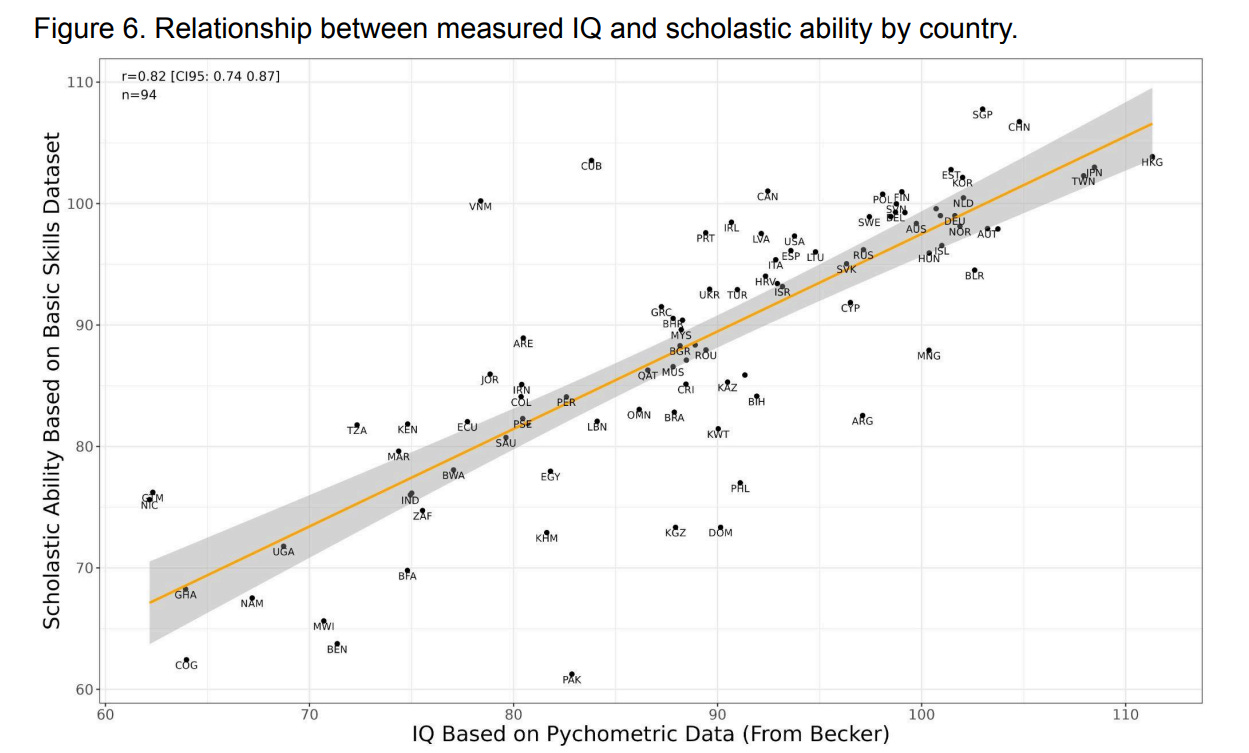

The national IQs also have strong external validity: if one averages the IQs from the Becker dataset and compares them with estimates based on PISA/PIRLS/TIMSS/etc scores, you get a correlation of 0.82:

Definitely not ideal, but far from “bologne”.

On the topic of changes in intelligence: I have a post that plots how IQs and test scores have changed in about 50-100 countries. In my opinion, it is not useful to estimate different IQ averages by year: the stability of individual countries is too high and the amount of data available is too low. Anybody who disagrees is free to make their own version of the national IQ dataset that satisfies their personal preferences.

Beyond attacking the reliability of the national IQs, he notes that changes in IQ do not track changes in economic growth.

3. If IQ does change over time, why don’t observed changes correctly predict economic growth?

If we align each Cambodian cohort by when they turned 22 and were plausibly fully integrated into the labor force, the 1973 cohort is 1995, the 1993 cohort is 2015, and the 2007 cohort is 2029. What was the growth rate around those periods?

The obvious answer is that the individual samples are of low quality, so the cohort differences are largely due to measurement error and not true differences. Which is what he’s implying, I think, but that circles back to my argument that inaccurate subsamples =/= inaccurate overall averages.

He then questions that there can be as many low IQ Africans as the national IQ dataset implies, meaning that either the averages are not that low or the distribution is not normal:

4. Do countries with low estimated mean IQs still have approximately normal IQ distributions around those means?

This is I suppose just a clarification question. But when somebody says “The IQ of a country is 102,” I assume they mean 102, with a standard deviation of 15 points, because conventionally IQ has a standard deviation of 15 points.

But does that hold when a country’s IQ is estimate at 65? Because if so, shockingly large shares of people would have IQs in the 20s, 30s, and 40s. IQs that low are not just going to have a bit less numeracy and poor abstract reasoning. People with those IQs even without other idiopathic sources of low IQ are disabled. They do not create social worlds. They are constantly dependent on others. They are exceptionally rare in well-studied populations in the West: almost all such extremely low IQs are due to some kind of profoundly disabling conditions. But if low-estimated-IQ countries have approximately normal distributions of IQ with similar SDs as high-estimated-IQ countries, then a whole lot of people there must have non-idiopathic extremely low IQs, and I just am not remotely convinced of that.

The distribution of African IQs is indeed normal¹, well, roughly normal: a left tailed bell curve at that.

Every time somebody questions low African IQs, one is obligated to link to the classic response: super low IQs do not mean the same thing when comparing two populations because intellectual disability is caused by two different components — multiple small, genetic effects or a massive, singular effect like Down syndrome. The former is less associated with deficiencies in the ability to function normally, while the latter is often accompanied by a pathological personality or even physiological defects.

Therefore, an African with an IQ of 50 probably just got a bad environmental and genetic dice roll, while a European with an IQ of 50 might have down syndrome or a similar genetic condition. Because of that, super low IQs do not describe functioning to the same degree in both populations. As for whether cognitive tests are biased measurements of abstract reasoning between Africans and Europeans, I am inclined to think that they are to some degree (favouring Europeans/developed nations), though the rank order that is observed in national IQ datasets reflects real differences.

The rest of his post was paywalled, and his arguments were of too low quality to be worth paying for, so this is where my response ends. Sometimes, a great man in one area of expertise can have better judgement on other fields than native experts.

Unfortunately, Lyman Stone is just not that guy.

Rather telling that he said that if Emil Kirkegaard responded to him, he would not respond back. Those are the words of a weak or unmotivated man.

I didn't even notice he wrote another post. But after I replied to his first post, he resorted to lying on Substack. Weird guy.

1st mistake of this post is to assume IQ is even a thing worth debating.

2nd is this part here:

>He’s ultimately wrong, but it does not really matter in this situation. The correlation between the average IQ of two parents and the IQ of their child is about 0.6; regardless of whether this correlation is genetically or environmentally mediated, if less intelligent people have more children then future generations will become less intelligent.

So A) Smart parents should breed smart kids is eugenics 101, and if it was right, anyone who was born countryside Germany would be the new Einstein nowadays. This nurture vs nature false dichotomy needs to stop: It is nurture. Intelligence is nurture, period. Good fitness does help, not rarely it is the deciding factor. The same as having good nutrition is. Is genetics what defines intelligence, no, non starter, no. We'd be discussing the semantics of it for a year, throwing papers at each other for days, and the fact will still be that given good fitness, intelligence can be taught, thanks to how we engineered education, period. Saying 0.6 of the results are on my side regardless of nurture or nature is the scholarly version of a "variables can be all I want and if you don't like it find a billionaire yourself to sponsor your own research";

And B) "if less intelligent people have more children then future generations will become less intelligent" they already do, you don't need future generations to see that, every numnum with a phone is living proof of that. However, the hype is that AI will further enable societal dysgenics, the same way that money increasingly allowed the worst among all people ever to have a chance to procreate. Calling it international dysgenics is just a way to be anti immigration (which is fine, everyone's entitled to a position here) but people don't really broad scale breed with interlopers since forever, and I think it is correct to question anyone making a projection that this will change, merely because culture matters.

>Wealthy people tend to be more intelligent than poor people. Is it really a mystery that the same occurs between countries?

Nurture. Sponsorship. *Money*. Sponsorship. Nurture.......

If you indulge me in rewording that sentence: "Wealthy people are given better opportunities to ultimately promote more intelligent experiences than those less fortunate. At nation scale, while some would say this escalates, the fact is that elites and geopolitical interests ultimately promote and project whatever stats they want, so it is a mistake to generalize, particularly over long time periods."